The Image, Deconstructed is located here:

http://www.imagedeconstructed.com/

Thanks for everyone's support!

Spotlight on Ben Depp

TID:

Thanks for taking the time to share your thoughts

on this difficult image. Please tell us a little bit

about your background first.

BEN:

I'm working in Haiti these days. I moved to Haiti in 2008, and I

worked as a staff photographer for an NGO for two years before

going freelance. I had been freelancing for a few months when

I made this picture.

Cholera was introduced to Haiti by the UN soldiers almost exactly

a year ago (and 6,500 people have died as a result). The latrines

on one of the bases were draining straight into a river. A few weeks

before I shot this particular image, I photographed the funeral of

one of the very first deaths by cholera on assignment for The Times.

As I watched – and photographed - the epidemic's spread across the

country, it seemed to me that the official numbers from the Haitian

government were too low. The immediate response was such that I

didn't get the sense people were really grasping the gravity of the

situation.

TID:

Let's talk about covering cholera in Haiti. What was going

on in your mind before making this image?

BEN:

I don't like news stories that start with “Haiti is the poorest country

in the Western hemisphere.” While covering cholera, I didn't want to

be doing just another Haiti-is-so-poor-and-screwed kind of story.

But cholera was (and still is) very serious. Although I avoid the doom

and gloom stories as much as possible, I felt like this was an important

one to follow. People were literally dying within hours of contracting

the disease, and I felt a need to try to convey the real sense of urgency

that would push donors, NGOs, and the government to take things

more seriously.

Cholera is so easy to treat. It's senseless for so many people to have

died (and still be dying) with all of the resources that are actually

available in this country. Many victims have died simply because they

or their families didn't know that they should go immediately to a

treatment center upon exhibiting symptoms.

After the first month or so, when there was no shortage of coverage,

and, rightly, some clinics stopped allowing photographers inside.

Cholera pictures were available for anyone who needed them, and I

stopped covering it.

TID:

Let's talk about the day you made the image.

BEN:

The first cases of cholera had just been reported in Port-Au-Prince.

With the unsanitary conditions in camps and lack of potable water

accessible in shantytowns, I was terrified about what that meant for

the city. Another journalist and I went out on motorcycle to see

what situation was like. I expected to see people dropping dead in

the streets and, literally, that's what we found. First, we came across

one victim dead on a sidewalk. Fifteen or twenty minutes down the

road we came across a young man who was still alive, but barely. His

mother was trying to take him to a cholera treatment center and he

had collapsed a mere few hundred feet from the entrance. He was on

the side of a fairly major road that runs across along the bay of Port-

Au-Prince. I shot a couple frames and then my friend and I tried to get

the staff at the treatment center to bring over a stretcher. We thought

they were on their way with the stretcher, so we went back to him and

kept shooting. He died within a few minutes.

TID:

As you started making the image, what was going on

in your mind?

BEN:

I was mostly thinking, “Where the hell are the people with the stretcher?”

It didn't seem like dragging him to the clinic was a good idea. Honestly,

I was also thinking about how to compose pictures to do justice to the

situation - there was the broken fence behind the guy casting really nice

shadows, which made the scene more ominous looking. There was also a

canal in the background that I felt alluded to the Styx, “the river of hate”

in Greek mythology that separates the world of the living from the world

of the dead. I wasn't able to include it in the image because it was too far

away. Coming across this type of situation is rare – yes, even in Haiti - so

I didn't want to screw it up and or miss any important details.

TID:

What were your concerns as you made the image,

and what was going on in the outside area of the

image?

BEN:

Well I was afraid that he was going to die and I'm always uncomfortable

shooting pictures of this kind of thing. I don't want to be exploiting suffering

just to make strong pictures if they're not also important pictures. I only

had a 20mm lens with me that day, so I was physically pretty close to him

and I didn't want to upset either him or his mother with my presence.

Outside of the image, a few young guys were standing nearby, watching.

They were scared to get too close to someone with cholera. Meanwhile,

the mom was frantic, wailing and walking around in circles. As he died

she was trying to give him water, as if in denial that she was losing her son.

TID:

What impact did this have on you emotionally?

BEN:

Seeing people die from cholera is particularly tragic because it's so

preventable. I was angry at the injustice of it, especially since the cholera

deaths are really a direct result of systemic issues of greed and corruption.

It's criminal that the water and sanitation infrastructure isn't better here.

It could be, but it's not. It's also criminal that the UN hasn't taken

responsibility for introducing cholera to Haiti. It still makes me angry.

My sister was dying of cancer while I was shooting this, so I was processing

that too. Anticipating her death made me more emotionally connected to the

people I saw dying of cholera. When the young man died, I was very conscious

of the process of his death. He was half awake, a minute later unresponsive

and then he stopped breathing and I was wondering the whole time if that's

what it would be like when Martha died. I was in Haiti for the earthquake in

January of the same year and though I saw hundreds of maimed and dead

bodies, I had still never witnessed anyone passing from life to death. 2010

was a heavy year for me and I'll be affected for the rest of my life by the

succession of traumatic events, but I wouldn't say this one man dying had a

profound effect on me in and of itself. It's more the accumulation of loss and

witnessing suffering.

Ten minutes after shooting this image, I came across a ten-year-old boy dead

in the road. His mother hadn't understood how quickly cholera could kill him,

hadn't been able to take him to a clinic and now that he was dead she didn't

have money to do anything with the body, so she put him in the road for the

government body collectors to find.

TID:

You said, "It's more the accumulation of loss and witnessing

suffering" that has had an effect on you. What effect has it had?

BEN:

I think I have some PTSD. I've always been easy going and in the past

two years, I have become less patient, more easily irritable, more

emotional, and at the same time, less affected by shocking things that

maybe should have an effect on me. I think all this is pretty normal

given my experiences. I'm still pretty laid back so the changes in my

personality are somewhat relative but are still unnerving for me.

TID:

What did you learn from making this image?

BEN:

What makes this image successful is the focus on the mother and the fact

that I was able to capture her grief. I don't think many of us can relate to

dead bodies in an emotional way, but we can all relate to grief - and I would

guess that that's certainly the most true for mothers who see this picture. I

only understand this now as I look back at the pictures in the process of

grieving the loss of my sister. At the time, I was just trying to capture everything

that was happening.

TID:

What surprised you about making this image?

BEN:

I was surprised when all the elements came together. I was trying not to

intrude too much on this woman's personal space. To frame the image,

I was able to position myself so that she walked back and forth in front of me

and I didn't have to follow her with my camera in her face. I was also a bit

surprised that nobody minded that I was shooting pictures of this situation.

I think that that was only because the people around had seen me try to

engage with the dying man and try to get help for him.

TID:

How has working in Haiti changed you as a photographer?

BEN:

I'm still learning all the time and my work is improving. I'm learning

a lot from other photographers working in Haiti, both on shooting

stories and how the business side of freelancing works. I'm slowly

becoming more successful freelancing which is a good feeling. Since

I've been here for three and a half years and have really developed as a

photographer at the same time, I'm not sure what I can directly

attribute to Haiti so much as just working full-time and being

involved in a dynamic community of photographers.

TID:

What do you wish people knew about covering

Haiti that you think most people don't know?

BEN:

If you haven't worked in Haiti, you should depend on a good fixer. In Haiti,

everything is based on relationships and you need to be able to engage with

your subject and establish a certain level of trust. This is true everywhere,

but decades of external intervention and power imbalance make Haitians feel

particularly exploited by foreign photographers. Without good relationships,

shooting in high-stress situations can also be dangerous. Several photographers

I know almost got killed covering cholera. Because UN troops introduced the

cholera, there were rumors that foreigners were spreading it on purpose and

in several instances, photographers following the trucks picking up the bodies

of victims got attacked. Their fixers were able to negotiate on their behalf.

TID:

In conclusion, what advice do you have for people

covering these situations?

BEN:

Try to be a human before being a photographer - if you have the chance to

save somebody's life, do it. Walking away from a malnourished child on the

edge of death or a cholera victim that needs transport stays with you.

Don McCullin says it best:

I have been manipulated, and I have in turn manipulated others, by recording

their response to suffering and misery. So there is guilt in every direction:

guilt because I don't practice religion, guilt because I was able to walk away,

while this man was dying of starvation or being murdered by another man

with a gun. And I am tired of guilt, tired of saying to myself: 'I didn't kill that

man on that photograph, I didn't starve that child.' That's why I want to

photograph landscapes and flowers. I am sentencing myself to peace.

I sometimes wonder how long it will be

before I'll need to 'sentence myself to peace.'

+++++

Ben Depp has worked as a photojournalist since 2005 and hopes to make a living taking pictures for many years to come. He has entered several photo contests but never won. Recent clients include Newsweek, The New York Times, TIME, L'Équipe and The Times. Ben still lives in Haiti with his wife and cat.

http://www.bendepp.com/

+++++

Next week we'll explore this telling image of the Texas drought

by Austin American-Statesman photographer Jay Janner.

As always, if you have a suggestion of someone, or an image you

want to know more about, contact Ross Taylor or Logan Mock-Bunting:

ross@imagedeconstructed.com

logan@imagedeconstructed.com

For FAQ about the blog go to:

http://www.imagedeconstructed.com/

Spotlight on Matt Roth

TID:

Thanks for taking part in this and sharing your thoughts.

Please tell us a little about the backstory of the image.

MATT:

Ross! Or should I call you TID? Thanks a ton for letting me be part

of this super-cool blog. I'm humbled and stoked!

Back when I used to be a staffer for the Patuxent Publishing Co.,

one of our products I would shoot for was Howard Magazine. It's

one of those hyper-local, glossy, lifestyle mags targeted for women

from 35-60. We got a new art director, Michele Moy. It went from

something stodgy and predictable, to a fun, visually engaging magazine.

Our Cadillac issue was the annual Best of Howard edition. The awards

are poll-based, so whoever has the most friends wins. It had nothing

intrinsically to do with quality. That being said, corporations like The

Cheesecake Factory would win "Best Dessert." But being a true hyper-

local publication, we would only feature the local winners.

Before the winners were picked, the magazine team, Creative Director

Michele Moy, Designer Brian Young, one other photographer (Drew

Anthony Smith in 2009, and Sarah Nix-Pastrana in 2010), and I would

brainstorm. We looked through the categories and picked which ones we

thought might be the most interesting to illustrate. I picked the ones I

wanted to shoot, and Drew and Sarah picked the ones they wanted. And

for most of the shoots we also had four pairs of hands to drag gear in,

set up, troubleshoot and break stuff down. These shoots gave me a taste

of how much I LOVE working with a crew.

We had room for 6 images -- 5 full page/double trucks and one cover.

BIG BEAUTIFUL PLAY!

Ever since Michele started, she's been really good about reinventing the

magazine. She was also blessed with a boss who was expertly hands-off.

That is to say, she knew what was going on, but knew not to meddle in

things she's not trained for (i.e. photography and design). So Michele was

given the keys to the car, so to speak. She also knew to trust us

photographers and be ready for surprises -- which is good for me.

I don't have the temperament to really WANT to sit down and plan

something out. As a result I'm pretty good at being, uh, for lack of a

better phrase, creatively resourceful on shoots. All that means is, I'm really

good at "making something out of nothing."

Truth be told, I get a little anxious when stuff is over-planned -

especially when it comes from someone else's brain. In my experience,

when expectations for a shoot are too tightly prescribed I tend to make

lackluster images.

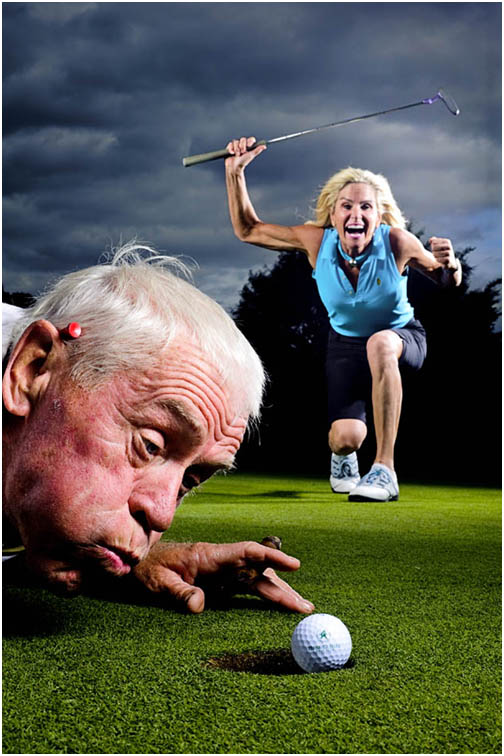

There are some exceptions, though. The Best Golf Course of Howard

County illustration was VERY planned out. We went on an extensive

tour of the golf course to find the right tee. There were a lot of logistics

to worry about. For example, what if someone needed to play through?

We also thought up the story beforehand: Warren Klauschus is trying to

blow Martie Browning's ball from going into the hole. We needed genuine

characters, visual storytelling layers, a clean background and a ball that

looked like it was about to drop in the hole. Before we brought out Martie

and Warren, we had a water-tight formula and stuck with it. The ball, by

the way, was super-glued to a golf tee and jammed into the lip of the hole.

And that's basically how most of these shoots went.

Then there's the Plumber of the Year photo. I had a vague idea of how I

wanted to shoot this. We also didn't get a chance to scout his location

before the day of the shoot either. The only thing I really wanted was

water spraying at the camera! Luckily, Ken Griffin was up for whatever,

and he had Plexiglass for me to stand behind. That big wrench? Totally his

idea. He asked, "Do you want me to hold something? I have a giant wrench."

I was like HECK YES! I've learned to be open to my subjects' whimsies.

TID:

That gives us a great context to the Vet of the Year shoot, thanks.

Now let's talk about that image specifically.

MATT:

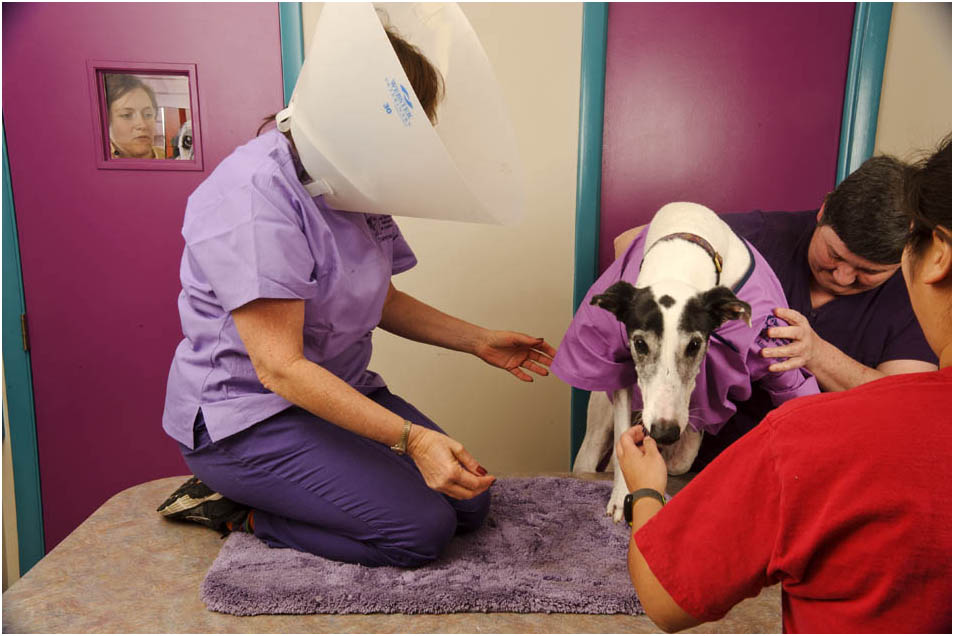

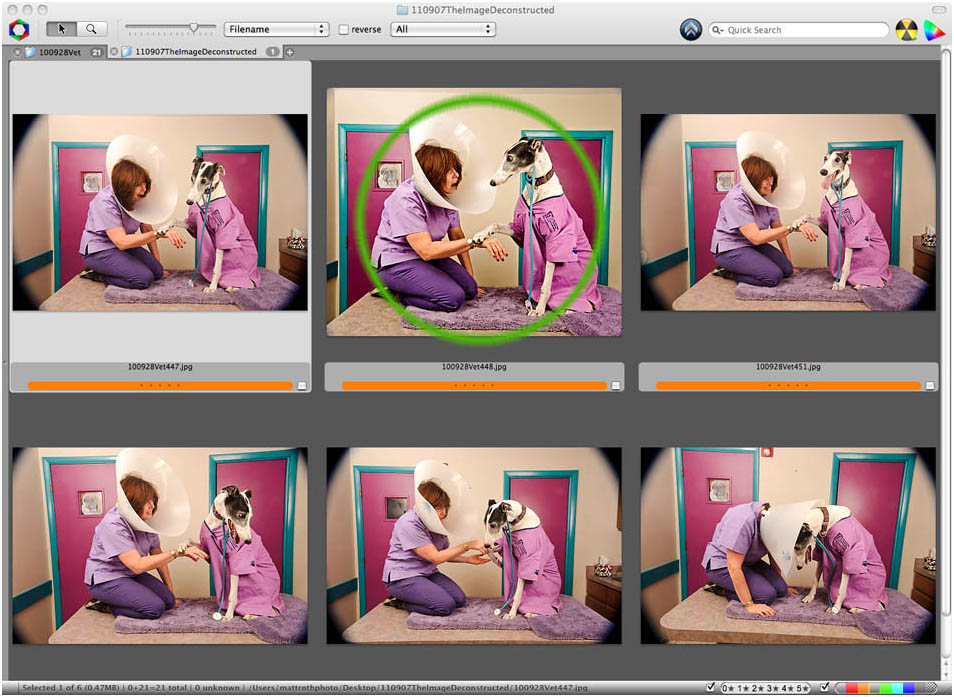

The Vet of the Year shoot was somewhat similar to the golf course shoot.

We scouted the location, met the human players and procured a "cone of

shame." We also had a story thought out. Admittedly, it was a bit less witty

than the golf photo. We wanted visual storytelling layers: a sad, sick, cute

dog, the caring vet, a connection between the two, and a concerned owner

peeking through the window.

A quick digression to set up my next point: the one thing I've learned over

the years is to shoot and EDIT for the READERS. I think journalists, editors

and managers can sometimes lose sight of who their real audience is. When

I was tired of getting yelled at by my bosses, the quality of my content became

weak. I knew the bosses wanted photos that told the complete story, regardless

of how underwhelming the image. I always wanna win the page flip war. If I

make an image -- scratch that -- if I can get an image PUBLISHED that makes

the reader intrigued, then I win! And, y'know, so does the reader.

If a reader sees a photo and reacts audibly then you have a great photo.

Unless it's groan from boredom.

"Hahahahaha!"

"Awwwwwwww."

"Wow!"

"What the…?"

"Gasp!"

"Sigh."

For all these Best Of photos I wanted to elicit an emotion by telling a story,

typically a funny story. With the vet shoot I was initially trying to make a funny,

yet cute picture that would make the viewers go, "Awwwww."

But by the grace of Dr. Barbara Feinstein, I ended up with this amazingly

absurd picture. I would've never story-boarded this image. And let's be honest,

if I pitched this idea, it'd most likely get thrown out. This wonderful instant

is the sum of a few hours of patient humans dealing with two remarkably

shy and uncooperative dogs. The first half of the shoot starred an entirely

different cast. And we made some pretty good photos, which I've included.

I think the one we almost used was the thermometer photo.

But when Dr. Feinstein came in, she suggested a little role reversal.

I was like, "Sure! You can put the cone of shame on your head. Are there

scrubs that'll fit Moosh? Oh! And a stethoscope! Can Moosh wear your

stethoscope, too?" But as you can see from the contact sheet, Moosh

cooperated for half a second -- which is good because all I needed was

1/160th of a second (waka-waka!)

What makes this photo work? It's their connection! I believe Moosh is

genuinely concerned for Dr. Feinstein in this picture.

TID:

This looks like it took a lot of time to organize. Did you call her in advance

to prep her, or the vet in any way?

MATT:

Oh yeah. Totally. Ha! You can't just barge into a vet's office, lights in tow,

flatter them with an award and expect them to give you like two hours of

their time. We were pencilled in. Heck, we were pencilled in for the location

scout. That alone took almost an hour. Don't get me wrong, looking around

the vet's office doesn't take that long. But when scouting locations, you

have to think about things like: Is this a good/clean/appropriate background?

Does this setting say "vet's office?" Will we be in the way of normal business

practices if we take over this space? Where will we put the lights if we use

this space? Will the lights create an unavoidable glare in that reflective

surface? And I had to be cautious of how close I was to the cats -- 'cause

I'm allergic! Don't worry, I took my pills. And debatably more important than

finding a good location, we have to establish rapport with our subjects or,

as I sometimes like to call them, "the protagonists!" Typically, but not always,

we try to use the business owners for these shots. Luckily, both owners

were game and very fun to work with.

TID:

You make this sound a lot easier than it probably was, mentally, to pull off

(which is a compliment to your style.) Could you please talk about how

you interact with subjects in preparation for a shoot, and also on

location?

MATT:

Ha! Thanks. I suppose in some sense, everything's easier in hindsight. But

if you'll let me diverge into another abstract truism, I'll answer this question

with a bit more idea-driven girth. Not to put too fine a point on it, you have

to know how you affect situations.

Like most photographers who cut their teeth in a photojournalism program,

we're told we need to be "flies on the wall." The thing I learned about myself

is that I can't operate like that. Well, I can, but I end up being that creepy,

bearded guy in the corner… with cameras. Yeah, who wants to talk to that

guy? I do think the "fly" approach works really well for the people who have

a quiet, ghost-like energy. But the thing is, it doesn't work for everyone.

You have to play to your strengths. Me? I tend to bring a loud, gregarious

energy into the room. That doesn't mean I make big, flamboyant entrances

(Ta-daaaa! Who wants some Matt Roth Photo action?) But it does help to be

self aware. More often than not, I realize that people notice me when I walk

into a room and yes, I realize how conceited that sounds. Trust me. It's not

for my looks (flips hair, purses lips, trips over an ottoman...) The point is,

I'm less successful when I attempt to be inconspicuous.

So, I try to ethically become part of the scene. I meld into it without messing

with it. Does that make sense? And when you set the rules of engagement

with a subject it helps to have a few boilerplate phrases. In fact, I learned a

really good phrase from my friend Patrick Smith. Rather than asking the

subjects to "ignore me," I ask them to "act like I don't have a camera." It might

sound like I'm splitting hairs, but I find asking people to ignore me (and my big

dumb energy) their mannerisms and eye contact look like they're avoiding

something (me!) in the pictures.

A lot of people, viewers included, understand that game, and know what

it looks like. But when I ask them to act like I don't have a camera, I also

encourage them to talk to me and ask me questions, if they want to. It's

great! Not only is the shoot more comfortable for both me and the subjects,

but it gives them license to relax. I'm not asking them to avoid the wooly

mammoth in the room. And of course, when people talk, you get to flex

your journalism muscles too. So if any of you fledgling photojournalists

out there are also failing or feeling weird using the "fly" approach,

switch your gears up. Get close. Be Chummy.

So to answer your question, my loud energy makes a ton of sense in a

photo shoot scenario. I actually feel like I'm on top of my game when

I have or am part of a crew. I guess when I have a crew to lead, I become

more confident and happy, which ultimately, puts the subject at ease.

Of course, it also helps to have extra hands on set too. That way I don't

have to move light stands and sweat the small stuff. I can just focus on

the subject.

I genuinely like people too. So I try to have "the protagonists'" best

interest at heart. And here's the kicker... I also make sure they know that.

For my Athletes of the Year photos, for example, I told them

I want them to look like they're the stars of a Nike ad!

Think about it. Most of them reached their athletic apex being named

All-County. It's a big deal for them, and I think that's an important issue to

address. But the Baltimore Sun and the Washington Post (to a lesser degree)

so often employ the studio cattle call approach. Don't get me wrong, I

understand that method from the newspapers' perspectives, it saves time,

it makes the process easier. It's "streamlined," which means rigid and often

results in boring photo play. I'm not knocking the photographers.

I'm knocking the system. Almost every shooter on both of those staffs is ultra-

capable of banging out awesome portraits if they were given the time and

freedom. We were lucky at Patuxent. But for obvious reasons, the athletes

I've shot really don't like the cattle calls. So I use this opportunity to try to

make them feel awesome! And they'll gladly give me two hours

just to make sure they don't look weird kicking a soccer ball.

Form is important. …and remember, photos are forever.

And yes! I let them see the back of the camera, too. Only for portraits,

though. The exception being unless the issue I'm illustrating calls for an

unflattering picture of the subject, or if I've been given explicit instructions

to not show the subject the shoot. This does two things, it lets them know

that I'm genuinely interested in making sure they look good. And it lets

them know where they need to make adjustments. People are picky about

very specific things. Personally, I like knowing they LOVE the photos. I try

to be as transparent in my motivations as I need to be. If they understand

where I'm coming from and what I need from them, they're more likely to

play ball. Of course, there are exceptions. The end goal is to come to a

meeting of the minds. And like I said earlier, I've found a lot of success

from letting my subjects….er, Protagonists! add to the shoot.

TID:

Can you briefly discuss how you approach lighting

for this and other assigments?

MATT:

Haha! Uh, a lot of people have me pegged as a lighting wizard… which

I'm not. I think I'm successful with lights only because I don't think they're

scary. I think using lights is fun. Each shoot is an experiment.

Sure, I have a few clutch set ups I rely on when I need to. I think

that whimsical attitude keeps lighting fun for me. But for this set up,

I think I shot through an umbrella behind me to my right and I bounced a

light off the ceiling to my left. I also set up a small speedlight zoomed to

105mm in one of the cabinets behind the subjects for some rim light --

but I'm pretty sure the batteries died way before this shot happened.

This photo doesn't rely on the lighting set up, and this was by design.

Sometimes lighting can be the reason to look at a photo, and our goal was

to tell a story. Lighting was only there to optimize the image's quality and

to ensure we could shoot at ISO 100.

TID:

What problems did you face during the making of this

image, and how did you overcome it?

MATT:

Well, the obvious problems we faced were the dogs, which we anticipated.

They lost interest in what we were doing fast. The flash bursts scared them…

Well, that and they were in a vet's office. We all know how dogs get in a vet's

office, right? I'm sure if we had a budget, we would've hired a trained dog.

Truthfully, I'd say most of the shoot went wrong. But that was fine. We really

just needed three usable photos.

I guess I usually go into shoots expecting things to go wrong, so when

they do, I just deal with them -- and learn from them. Success is a process,

y'know? I knew the best photos would involve some kind of connection. And

eye connection is pretty powerful. Of course, timid dogs don't make eye

contact, so I tried looking for different stories to unfold. We almost went

with a photo of the first vet checking the first dog's temperature. It's funny

because those thermometers go up the dog's butt. And butts are funny.

But more than that, there was a pretty good little story being told too,

with concerned owner peering in from the outside window. We could've

easily wrapped after that shot, but it didn't quite have that, "Oh, hell yeah!"

effect I really wanted. So, I powered through. I knew there was better. And

a lot of you shooters out there can attest to that electric feeling you get when

you make that one "best image." Well, I got that feeling when I made the image

we're deconstructing.

The whole shoot was like climbing out of a valley.

TID:

What have you learned about yourself that you didn't know

by making these kinds of images?

MATT:

Well, let's see. We all know It's easy for photographers to get pigeonholed.

And it's easy for us to let ourselves stay in those pigeonholes. Because of

my Athletes of the Year photos, I've become known as a sports guy -- which

I'm really not. Don't get me wrong, I like athletes, but I'm kinda dense when

it comes to the world of sports. But after the modest success I received from

these Best of Howard shoots, I really wanted dig my own pigeonhole as a

concept photographer. Those shoots were so, so much fun to create. I got

to use my imagination! How fun is that? It also made me realize that while

I'm a fine, competent photojournalist, I'm way better at being a portrait/

concept/editorial/commercial/advertising/making-stuff-up photographer.

I've also learned a ton more about how to use lights more effectively and

blah blah blah... But more recently I've learned that I need to learn how

to put the lights away, too. Lights are great! But lights are also horrible.

TID:

What have you learned about other people?

MATT:

The lesson to be learned from this shoot is to always be open. Open to your

subject's ideas (sometimes they're really horrible though) and open to a

change in idea. It was an important reminder to me that plans are only

as good as they are successful.

TID:

Thanks, Matt. Any final thoughts or advice?

MATT:

I've had my fair share of photographers ask me to help them learn how to

use lights. A lot of them think it's something they really need to master. I

tell them, don't make lights so big and serious. Remember the first time

you picked up a camera? How magical was that? If you think about lights

as something you need to get better at, you'll miss all the fun.

++++

Matt Roth is still in his first year as an independent photographer in Baltimore, Maryland. Up until December 2010, he was a staff photojournalist with the Patuxent Publishing Company for 6 years. While there, he was NPPA's Best of Photojournalism's 2007 Runner Up Photographer of the Year for Small Markets (what a mouthful, right?) He won a bunch of other awards, but whatever... His current clients include AARP Bulletin, Education Week, The New York Times, The Sporting News, The Chronicle of Higher Education, and ESPN the Magazine. He's working on (and failing at) a project where he makes one portrait a day until he turns 34 next August. And even though the project has already suffered lapses, he'd rather earn a B+ than a W/F (withdraw/fail). He also hopes that analogy makes sense. So, if you'd like to be portraitized (traumatized through a portrait shoot) feel free to contact him. Matt Roth is also working on a Matt Roth Project where he makes portraits of as many Matt Roths as he can find. Like the NFL player, the three-point specialist who sits the bench for the Hoosiers, the guy who used to be married to and starred with Laurie Metcalf on the TV Show "Roseanne," as well as the guitar player from Austin (which is in the works!) and the brother of Susan -- who he briefly dated in high school. Seriously. He dated a girl whose brother had the same name as him. He already photographed the OTHER Matt Roth photographer... And of course, if you know any Matt Roths feel free to contact him. Matt Roth also thinks is weird to talk about himself in the third person.

www.mattrothphoto.com/

http://mattrothphoto.com/blog

e: matt@mattrothphoto.com

twitter: @mattrothphoto

++++

Next week we'll look at this powerful image by Ben Depp, one

of only a few photojournalists living and working fulltime in Haiti:

As always, if you have a suggestion of someone, or an image you

want to know more about, contact Ross Taylor or Logan Mock-Bunting:

ross@imagedeconstructed.com

logan@imagedeconstructed.com

For FAQ about the blog go to:

http://www.imagedeconstructed.com/

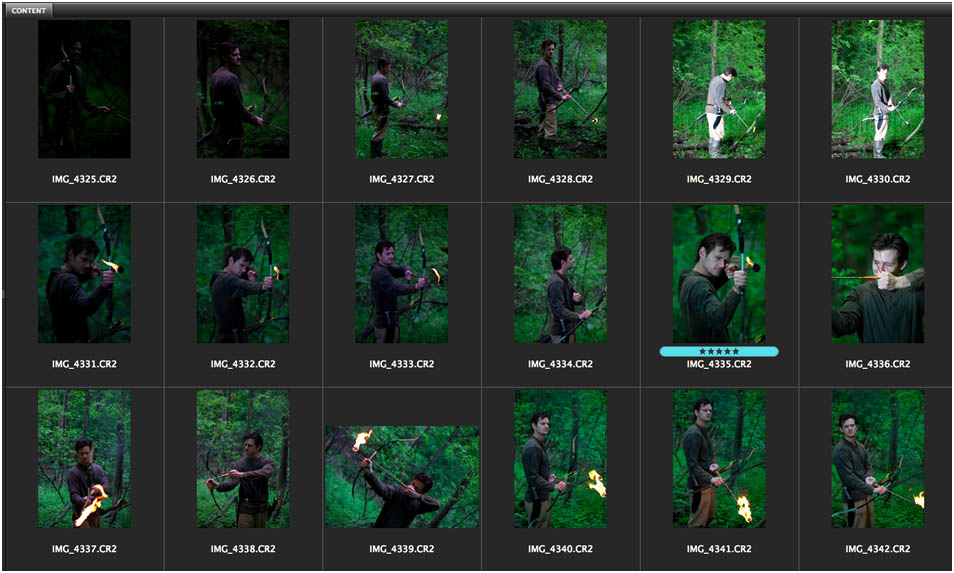

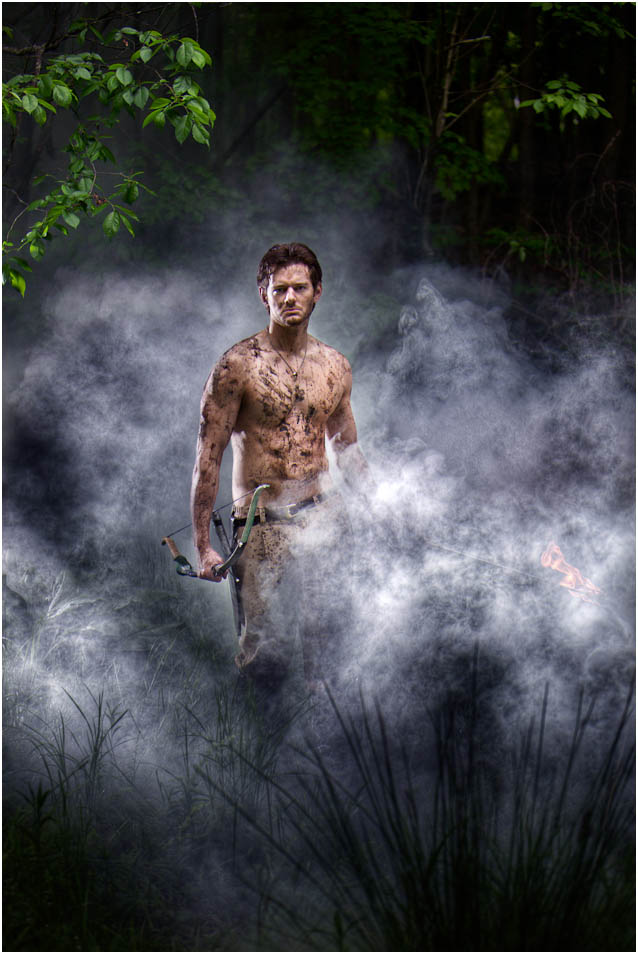

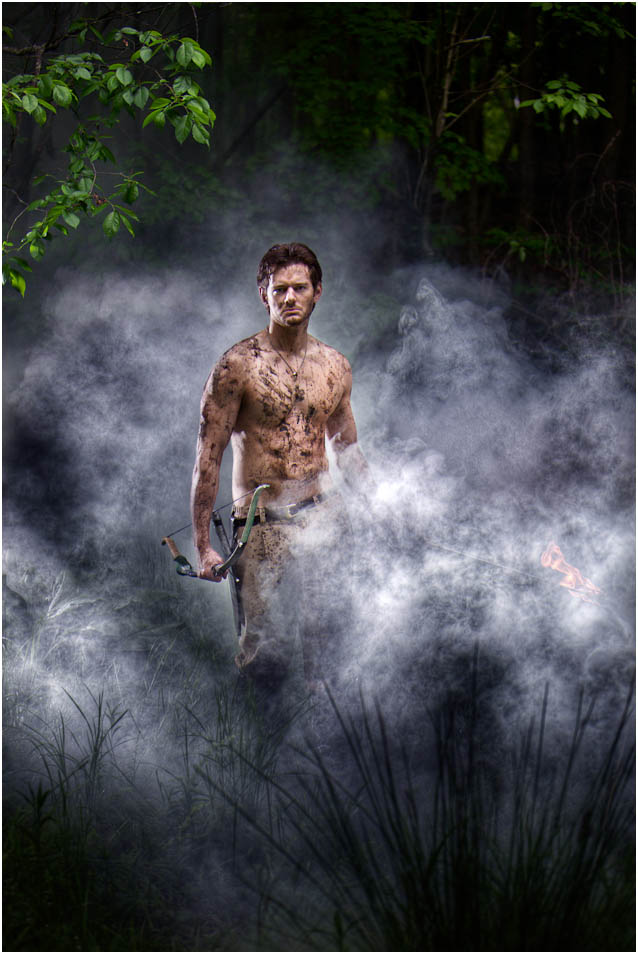

Spotlight on Daniel Kennedy/Nicole Truax

TID:

Daniel, thanks for your willingness to talk about this image.

Please tell us some about what this image is, and why you made it.

DANIEL:

Ross, it's an honor to have my image on this blog along side such

talented photographers. Thank you!

Joe Phillips, an aspiring actor and friend, hired my business partner and I,

Nicole Truax, to do a character shoot for his portfolio. Instead of the usual

straightforward headshot, we opted to go all out for a full character study.

This better shows the actor's potential to portray a certain look. Character

shoots offer actors the ability to create a body of work in a short

period of time that they can then pair with their film work to show

greater versatility; something very valuable in the entertainment industry.

So… a bottle of lighter fluid, several arrows, a bow, and 36 military-grade

smoke grenades later this is what we came up with. One of Joe's

skill sets is archery; he also has a British accent. So creating the

character of a warrior/archer was something that came natural, and

also a role he would enjoy playing.

TID:

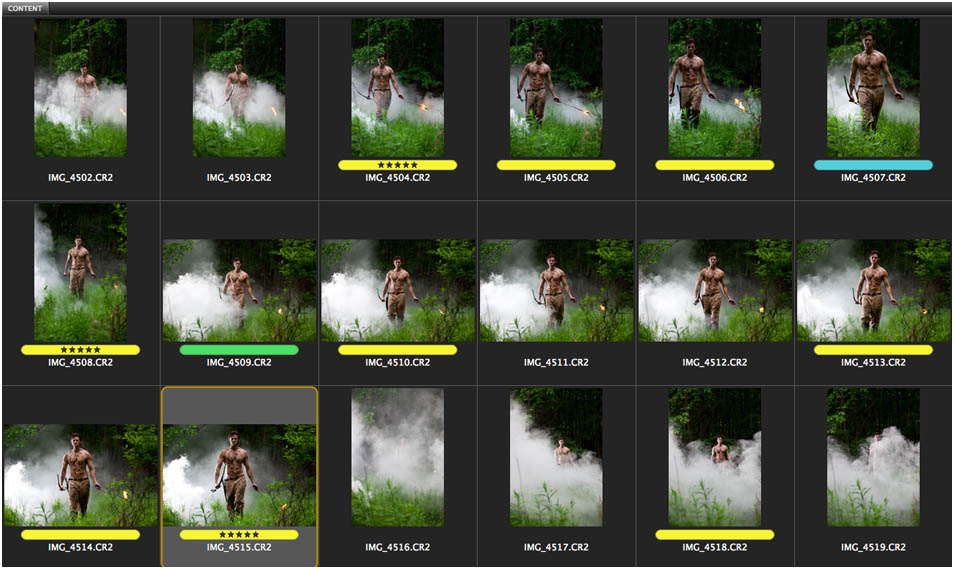

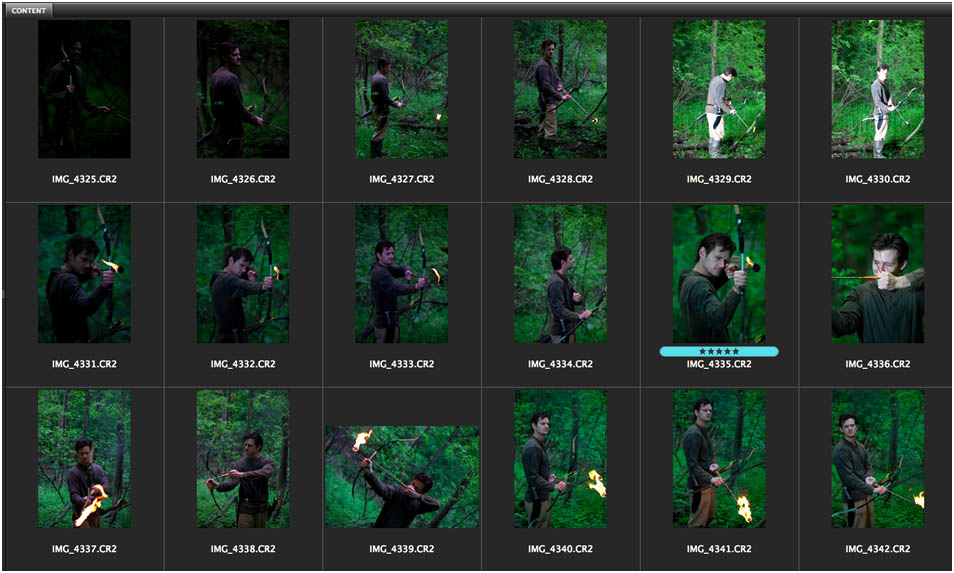

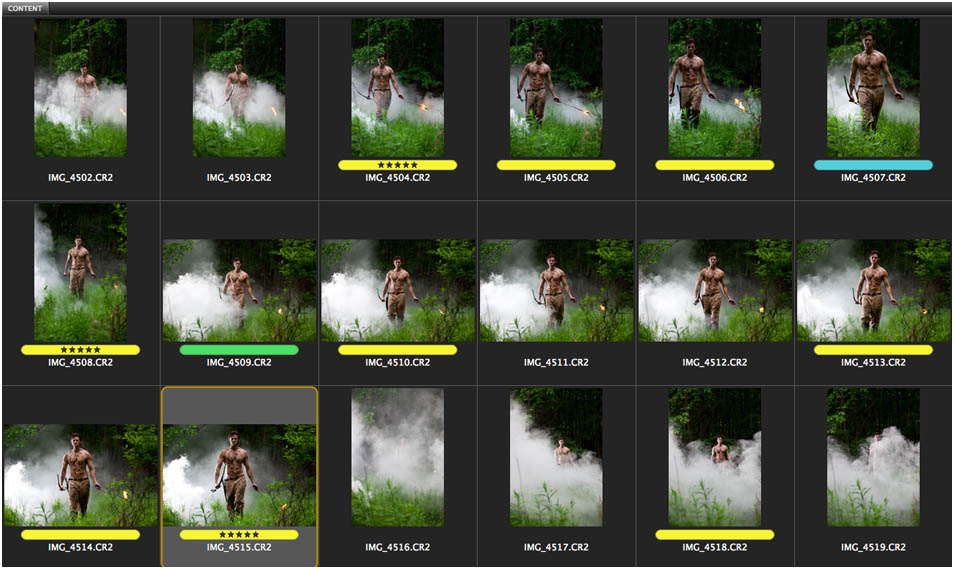

We're going to include a number of images from the shoot to give

people an idea of how this developed. It's interesting to hear your

thoughts, though, from the beginning. Can you talk about how you

mentally prepared for this?

DANIEL:

The idea for this started off very simple. Joe needed a shoot, and he

gave us a list of looks that he wanted. Nicole and I began to talk

about what we wanted and the first idea was very simple: take Joe

up a mountain and photograph him with a bow and arrow. At some

point Nicole said, "I wish we could light the arrow on fire."

"Well why can't we?" I said. "I know a way to rip up a shirt, tie it in a ball,

and light it on fire so it burns for a long time but burns relatively cool so

it's not dangerous."

"Really?" she asked me. "Let's do that," she said.

Then, of course, once we had a flaming arrow involved, we wanted to

put him in a swamp, make a ton of smoke, cover him with muck, and

give him a giant knife. I mean, isn't that the obvious progression of

thoughts? One thing may not have worked without the other, but with

everything together it becomes "cinematic." That is, as long as you get the

lighting and atmosphere right. I think we get bored easily and always

want to do something exciting and different. So it's natural for us to

get inspired by something and run with it.

To prepare, we also looked through thousands of photos and drawings

of warriors/archers on the Internet, and could barely find anything that

really helped. Often we make a folder of images that inspire us that we

find online. This usually helps give us an idea of good ways to light a

certain subject. Obviously we don't copy the images, but it helps to see

how other photographers have solved similar problems and it gets your

own mental gears turning. There was a serious lack of high quality

"Warrior/Archer photography." I wonder why? Maybe we can fill that void.

For the location we chose to meet at my parents' house in upstate New

York (about an hour and a half away from Nicole and I, a three hour trip for

Joe, and an hour trip for Colin, who also helped.) This was the best place I

could think of that we would have access to, and not get arrested. My

parents own three acres, and there are miles of woods behind their house.

Colin (a long-time friend/Army captain/weapons specialist) and I had played

paintball throughout high school in those woods and I immediately thought

of a swampy area for the location. I knew we had to do it there. We had

staged our own battles there for years, it just made sense to go back there.

It's weird, creatively I always find myself going back to shoot at strange

places I've been. It just seems right. If you visit enough areas, eventually

you'll have somewhere to go for anything I suppose.

TID:

Once you began the shoot, can you walk us through the next step?

DANIEL:

Basically, we first had Joe walk around wearing a green shirt and we lit

an arrow on fire to add drama. At first the photos didn't look believable to

me, they looked more like we were "pretending." I was worried that the

photos wouldn't resonate the way I wanted them to. I'm sure every

photographer can relate to starting a shoot you're really excited and anxious

about, and looking down at your first images on your camera's LED screen

and having a mini panic attack because everything just looks wrong --

nothing like you had imagined them to look in your head.

TID:

I'm a big fan of problem solving, so in this case, how did you

solve the problem of “pretending?"

DANIEL:

It looked like "pretending" because 1) that's what we were doing, and 2)

we didn't have the lighting figured out yet. Lighting is everything. So we

decided to see how things looked out in a more open, swampy area with

more sunlight pouring in. I had Colin McNulty assist with the shoot, and

you can see him placing some smoke grenades in one of the images.

I had Colin set off smoke grenades while I would shoot and relight the arrow

with Kerosene. Nicole and I often switch back and forth while shooting,

one working lighting and talking to the client while the other shoots. This

helps because when you're working lighting you're often closer to the subject

and can notice certain things that you might not from behind the camera and

vice/versa. I had started shooting in the woods, then had Nicole shoot in the

swamp at first. I handed off the camera to her and started to use an umbrella

to create diffused side lighting. After some trial and error, we moved back

into the woods and Nicole suggested we use side/back lighting with a bare

flash. This is where we finally got the lighting the way we wanted. I also had

a better understanding of how the light effected the smoke because I could

see it happening up close. Something I wouldn't have arrived at if we didn't

switch spots and jobs.

One of the major problems was with lighting the smoke. We had to figure

out an angle to illuminate the smoke without blowing it out, so we couldn't

have the light source in front or else it looked too fake. Again, we had to

overcome this to make the scene work.

The image became more believable at this point. We asked Joe to lose the

shirt and dirtied him up with mud and water; this made him look more like

a warrior and less the part of the actor playing the warrior. At the beginning

of the shoot, the shots kept reminding me of B movie stills and I hated them.

Everything changed once we got the lighting figured out (how to illuminate

Joe dramatically while also illuminating the smoke so it didn't become too

bright or dark.) We decided to move back into the swamp area and use the

same lighting techniques we had figured out while using more smoke grenades.

I crouched low and had Joe walk towards me while Colin set off more smoke

grenades in locations both up and down wind. I had him repeat this walk

several times to get different looks. Nicole walked slightly behind him while

he walked so the light source moved with him. The main image being

featured in this post happened at that time. This is where everything really

fell into place. At this point Joe was covered in mud, wet, relaxed and

shirtless in 40-degree weather. I think he finally felt the part.

Nicole and I would often stop to look at the photos on the screen and

collaborate on lighting, angle and composition. This is usually how we

work, passing the camera back and forth, throwing new ideas to each other.

TID:

You said you collaborated with Nicole on this shoot. In what ways do

you collaborate mentally?

DANIEL:

Nicole and I collaborate on every project. It's one thing that I think has

led so much to our growth. With two minds working on something it's

always easier to keep things fresh. We both have a similar view of what we

think looks good and our style has evolved together. Prior to the shoot, we

often bounce ideas off of each other, and are very honest if we think

something won't work.

The fact that we are both equal photographers in the business also helps

when managing people during a shoot. Sometimes as an assistant you

aren't really even allowed to interact with the clients. When we work

together we feel completely comfortable directing/talking to the subject

while the other person is focusing on technical aspects. So instead of just

having to isolate yourself for a minute in thought, which can be awkward

for a subject, one of us can always take point. In short, we do everything

as a team. I've worked with other photographers, and there's never the

same synchronicity unless it's with Nicole.

TID:

One of the reasons I admire this image so much is that too often we wait for

someone to give us an opportunity to be creative, or conversely, critique

others for our lack of opportunity. Can you tell us how old you are and how

long you've been shooting? I think it's insightful for people to know this.

DANIEL:

I'm 24, Nicole will be 24 this week. I started shooting in fall of 2006 when

I took my first B&W photography class at the Hartford Art School. Nicole

has been taking classes since she was very young; she was actually eight when

she took her first photo darkroom class. Professionally we have been

shooting since May of 2009, the month we graduated from college. We tried

to find jobs in the photography world, and actually applied to more than 300

of them in a four month period, went on two interviews, but were rejected due

to lack of experience. So since we couldn't find anything else, and rejected the

idea of finding a job in any other field, we started our own business in

September of '09, Linked Ring Photography. We've both interned for other

photographers, but came to the realization that you learn a lot more from

doing than watching.

For Joe's shoot, it really started out as simple head shots, which he's hired us

to do in the past. But as we sat and thought about it, we wanted to make this

particular shoot different. Take it to the next level. Something we could all

be proud of. When we shoot a job the way we've seen other people

do it, it just doesn't stand out as much to us. When we go the extra mile to

make something "crazy," it stands out.

TID:

What were some other problems you faced, and how did

you deal with them?

DANIEL:

As with any shoot, nothing works perfectly. The first problem was we

didn't have a generator or external power for our strobes. Our 500+ feet

of extension cord was short by 100 ft of where we wanted to shoot. So

we opted to use external flashes, which we would have eventually used

anyway due to their mobility and what we needed the light for.

It was raining on and off. Thunderstorms were set to come in during

the early afternoon so we had to shoot in the morning, both for light

and safety.

It was cold, there was poison ivy everywhere, and Joe had only slept three

hours the night before in order to travel for the shoot.

Smoke grenades are extremely difficult to control as the wind changes, etc.

Apparently it's not, "Hey, let's light an arrow on fire and throw some smoke

grenades and everything will be great." It's "Oh my God, how are we going

to do this now that everyone is suffocating and we can't see?" I'm exaggerating,

but it was a learning process and we literally used about 25 grenades

before we understood the wind currents, the way the light would interact

with them, as well as where Joe needed to be.

TID:

What did you learn about yourself during the making of the image?

DANIEL:

That in order to be as good as we want to be, we need to treat all shoots

like this. We need to always use our creativity and put in that extra

mile to make things complete. We need to put an emphasis on concept,

location, and props.

TID:

In the end, what did you take away from this experience,

and what advice do you have for photographers?

DANIEL:

Don't settle or cut corners to make something easier. Being a photographer

is hard. You owe it to yourself, and the people who believe enough in you to

pay you, to do everything you can to make your work the best it can be.

++++

Linked Ring Photography is a Greenwich, CT based commercial photography studio that consists of Hartford Art School graduates Nicole Truax and Daniel M. Kennedy. Like the original members of the Linked Ring Brotherhood, we believe that photography in itself is capable of the highest forms of art. Our mission is to create a new and exciting experience in each and every project through our concept-driven ideas and lighting techniques.

www.linkedringphotography.com/

++++

Next week we'll learn what happens when dogs attack, take over

the world, force us to wear cones and play fetch.

It's actually an image by Matt Roth, who specializes in creative portraiture.

I really love his work and he'll offer a lot of wonderful insight.

As always, if you have a suggestion of someone, or an image you

want to know more about, contact Ross Taylor or Logan Mock-Bunting:

ross@imagedeconstructed.com

logan@imagedeconstructed.com

For FAQ about the blog go to:

http://www.imagedeconstructed.com/

Daniel, thanks for your willingness to talk about this image.

Please tell us some about what this image is, and why you made it.

DANIEL:

Ross, it's an honor to have my image on this blog along side such

talented photographers. Thank you!

Joe Phillips, an aspiring actor and friend, hired my business partner and I,

Nicole Truax, to do a character shoot for his portfolio. Instead of the usual

straightforward headshot, we opted to go all out for a full character study.

This better shows the actor's potential to portray a certain look. Character

shoots offer actors the ability to create a body of work in a short

period of time that they can then pair with their film work to show

greater versatility; something very valuable in the entertainment industry.

So… a bottle of lighter fluid, several arrows, a bow, and 36 military-grade

smoke grenades later this is what we came up with. One of Joe's

skill sets is archery; he also has a British accent. So creating the

character of a warrior/archer was something that came natural, and

also a role he would enjoy playing.

TID:

We're going to include a number of images from the shoot to give

people an idea of how this developed. It's interesting to hear your

thoughts, though, from the beginning. Can you talk about how you

mentally prepared for this?

DANIEL:

The idea for this started off very simple. Joe needed a shoot, and he

gave us a list of looks that he wanted. Nicole and I began to talk

about what we wanted and the first idea was very simple: take Joe

up a mountain and photograph him with a bow and arrow. At some

point Nicole said, "I wish we could light the arrow on fire."

"Well why can't we?" I said. "I know a way to rip up a shirt, tie it in a ball,

and light it on fire so it burns for a long time but burns relatively cool so

it's not dangerous."

"Really?" she asked me. "Let's do that," she said.

Then, of course, once we had a flaming arrow involved, we wanted to

put him in a swamp, make a ton of smoke, cover him with muck, and

give him a giant knife. I mean, isn't that the obvious progression of

thoughts? One thing may not have worked without the other, but with

everything together it becomes "cinematic." That is, as long as you get the

lighting and atmosphere right. I think we get bored easily and always

want to do something exciting and different. So it's natural for us to

get inspired by something and run with it.

To prepare, we also looked through thousands of photos and drawings

of warriors/archers on the Internet, and could barely find anything that

really helped. Often we make a folder of images that inspire us that we

find online. This usually helps give us an idea of good ways to light a

certain subject. Obviously we don't copy the images, but it helps to see

how other photographers have solved similar problems and it gets your

own mental gears turning. There was a serious lack of high quality

"Warrior/Archer photography." I wonder why? Maybe we can fill that void.

For the location we chose to meet at my parents' house in upstate New

York (about an hour and a half away from Nicole and I, a three hour trip for

Joe, and an hour trip for Colin, who also helped.) This was the best place I

could think of that we would have access to, and not get arrested. My

parents own three acres, and there are miles of woods behind their house.

Colin (a long-time friend/Army captain/weapons specialist) and I had played

paintball throughout high school in those woods and I immediately thought

of a swampy area for the location. I knew we had to do it there. We had

staged our own battles there for years, it just made sense to go back there.

It's weird, creatively I always find myself going back to shoot at strange

places I've been. It just seems right. If you visit enough areas, eventually

you'll have somewhere to go for anything I suppose.

TID:

Once you began the shoot, can you walk us through the next step?

DANIEL:

Basically, we first had Joe walk around wearing a green shirt and we lit

an arrow on fire to add drama. At first the photos didn't look believable to

me, they looked more like we were "pretending." I was worried that the

photos wouldn't resonate the way I wanted them to. I'm sure every

photographer can relate to starting a shoot you're really excited and anxious

about, and looking down at your first images on your camera's LED screen

and having a mini panic attack because everything just looks wrong --

nothing like you had imagined them to look in your head.

TID:

I'm a big fan of problem solving, so in this case, how did you

solve the problem of “pretending?"

DANIEL:

It looked like "pretending" because 1) that's what we were doing, and 2)

we didn't have the lighting figured out yet. Lighting is everything. So we

decided to see how things looked out in a more open, swampy area with

more sunlight pouring in. I had Colin McNulty assist with the shoot, and

you can see him placing some smoke grenades in one of the images.

I had Colin set off smoke grenades while I would shoot and relight the arrow

with Kerosene. Nicole and I often switch back and forth while shooting,

one working lighting and talking to the client while the other shoots. This

helps because when you're working lighting you're often closer to the subject

and can notice certain things that you might not from behind the camera and

vice/versa. I had started shooting in the woods, then had Nicole shoot in the

swamp at first. I handed off the camera to her and started to use an umbrella

to create diffused side lighting. After some trial and error, we moved back

into the woods and Nicole suggested we use side/back lighting with a bare

flash. This is where we finally got the lighting the way we wanted. I also had

a better understanding of how the light effected the smoke because I could

see it happening up close. Something I wouldn't have arrived at if we didn't

switch spots and jobs.

One of the major problems was with lighting the smoke. We had to figure

out an angle to illuminate the smoke without blowing it out, so we couldn't

have the light source in front or else it looked too fake. Again, we had to

overcome this to make the scene work.

The image became more believable at this point. We asked Joe to lose the

shirt and dirtied him up with mud and water; this made him look more like

a warrior and less the part of the actor playing the warrior. At the beginning

of the shoot, the shots kept reminding me of B movie stills and I hated them.

Everything changed once we got the lighting figured out (how to illuminate

Joe dramatically while also illuminating the smoke so it didn't become too

bright or dark.) We decided to move back into the swamp area and use the

same lighting techniques we had figured out while using more smoke grenades.

I crouched low and had Joe walk towards me while Colin set off more smoke

grenades in locations both up and down wind. I had him repeat this walk

several times to get different looks. Nicole walked slightly behind him while

he walked so the light source moved with him. The main image being

featured in this post happened at that time. This is where everything really

fell into place. At this point Joe was covered in mud, wet, relaxed and

shirtless in 40-degree weather. I think he finally felt the part.

Nicole and I would often stop to look at the photos on the screen and

collaborate on lighting, angle and composition. This is usually how we

work, passing the camera back and forth, throwing new ideas to each other.

TID:

You said you collaborated with Nicole on this shoot. In what ways do

you collaborate mentally?

DANIEL:

Nicole and I collaborate on every project. It's one thing that I think has

led so much to our growth. With two minds working on something it's

always easier to keep things fresh. We both have a similar view of what we

think looks good and our style has evolved together. Prior to the shoot, we

often bounce ideas off of each other, and are very honest if we think

something won't work.

The fact that we are both equal photographers in the business also helps

when managing people during a shoot. Sometimes as an assistant you

aren't really even allowed to interact with the clients. When we work

together we feel completely comfortable directing/talking to the subject

while the other person is focusing on technical aspects. So instead of just

having to isolate yourself for a minute in thought, which can be awkward

for a subject, one of us can always take point. In short, we do everything

as a team. I've worked with other photographers, and there's never the

same synchronicity unless it's with Nicole.

TID:

One of the reasons I admire this image so much is that too often we wait for

someone to give us an opportunity to be creative, or conversely, critique

others for our lack of opportunity. Can you tell us how old you are and how

long you've been shooting? I think it's insightful for people to know this.

DANIEL:

I'm 24, Nicole will be 24 this week. I started shooting in fall of 2006 when

I took my first B&W photography class at the Hartford Art School. Nicole

has been taking classes since she was very young; she was actually eight when

she took her first photo darkroom class. Professionally we have been

shooting since May of 2009, the month we graduated from college. We tried

to find jobs in the photography world, and actually applied to more than 300

of them in a four month period, went on two interviews, but were rejected due

to lack of experience. So since we couldn't find anything else, and rejected the

idea of finding a job in any other field, we started our own business in

September of '09, Linked Ring Photography. We've both interned for other

photographers, but came to the realization that you learn a lot more from

doing than watching.

For Joe's shoot, it really started out as simple head shots, which he's hired us

to do in the past. But as we sat and thought about it, we wanted to make this

particular shoot different. Take it to the next level. Something we could all

be proud of. When we shoot a job the way we've seen other people

do it, it just doesn't stand out as much to us. When we go the extra mile to

make something "crazy," it stands out.

TID:

What were some other problems you faced, and how did

you deal with them?

DANIEL:

As with any shoot, nothing works perfectly. The first problem was we

didn't have a generator or external power for our strobes. Our 500+ feet

of extension cord was short by 100 ft of where we wanted to shoot. So

we opted to use external flashes, which we would have eventually used

anyway due to their mobility and what we needed the light for.

It was raining on and off. Thunderstorms were set to come in during

the early afternoon so we had to shoot in the morning, both for light

and safety.

It was cold, there was poison ivy everywhere, and Joe had only slept three

hours the night before in order to travel for the shoot.

Smoke grenades are extremely difficult to control as the wind changes, etc.

Apparently it's not, "Hey, let's light an arrow on fire and throw some smoke

grenades and everything will be great." It's "Oh my God, how are we going

to do this now that everyone is suffocating and we can't see?" I'm exaggerating,

but it was a learning process and we literally used about 25 grenades

before we understood the wind currents, the way the light would interact

with them, as well as where Joe needed to be.

TID:

What did you learn about yourself during the making of the image?

DANIEL:

That in order to be as good as we want to be, we need to treat all shoots

like this. We need to always use our creativity and put in that extra

mile to make things complete. We need to put an emphasis on concept,

location, and props.

TID:

In the end, what did you take away from this experience,

and what advice do you have for photographers?

DANIEL:

Don't settle or cut corners to make something easier. Being a photographer

is hard. You owe it to yourself, and the people who believe enough in you to

pay you, to do everything you can to make your work the best it can be.

++++

Linked Ring Photography is a Greenwich, CT based commercial photography studio that consists of Hartford Art School graduates Nicole Truax and Daniel M. Kennedy. Like the original members of the Linked Ring Brotherhood, we believe that photography in itself is capable of the highest forms of art. Our mission is to create a new and exciting experience in each and every project through our concept-driven ideas and lighting techniques.

www.linkedringphotography.com/

++++

Next week we'll learn what happens when dogs attack, take over

the world, force us to wear cones and play fetch.

It's actually an image by Matt Roth, who specializes in creative portraiture.

I really love his work and he'll offer a lot of wonderful insight.

As always, if you have a suggestion of someone, or an image you

want to know more about, contact Ross Taylor or Logan Mock-Bunting:

ross@imagedeconstructed.com

logan@imagedeconstructed.com

For FAQ about the blog go to:

http://www.imagedeconstructed.com/

Spotlight on Sol Neelman

TID:

Sol, thanks very much for participating in this blog. It's great

to look into the unique world in which you work, rooted in weird

sports, and we thought this picture was a great example.

Can you set the stage for this image?

SOL:

Thanks, Ross, for asking me to participate in such a cool photo

series. It's an honor. I'm sharing with you an image from Bring

Your Own Big Wheel, a fun bike race that happens in San Francisco

every Easter. It used to take place on Lombard, but the event has grown

so big, they now host it on Vermont Street.

TID:

Before we get too much into the image, let's back up and talk

about your path in photography. You seem to have found a

niche in your work for which you are known. Can you

tell us about your path to this?

SOL:

Well, I've always loved sports. Not that I was ever any

good at them. But I grew up as an only child with a

single mom. Sports was a language I could use to

communicate with other guys, to have something in

common with them.

My family has always been travelers. I went around the

world when I was 4. So I always knew I could travel and

I love to have new experiences and meet new people.

I stumbled onto photography in junior high school. One

of my best friends was in a photography class and I

wanted to do the same. Never thought I had found a

career there, but as I got older, the only thing that

interested me professionally was photography. It allowed

me to travel and to attend sporting events. And, believe

it or not, I was also pretty shy, so photography gave me

an excuse to be outgoing.

Around 2005, a colleague in the business asked me what

I love. It was a simple question, but one I hadn't really

given much thought to. I was so focused on working at

The Oregonian, doing the daily grind of Photo-J. I had

gotten a little sidetracked over the years. I told her I loved

sports, photography, travel and weird shit. And things clicked.

That same year, I attended Geekfest in Austin, a photo

retreat organized by aphotoaday.org founder Melissa Lyttle.

That was the first time I really shot for myself, not worrying

about what would run in print. And I had a blast. When I

returned home to Oregon, I made a point to search out fun

sporting events to photograph for myself. The first one was

roller derby, which was just starting to blow up again. From

there, I kept going.

I had also been working at the paper with Bruce Ely on his

brilliant photo column, Sidelines. We'd go to high school

events and look for photographic moments anywhere but

in the field of play. That approach to sports photography

had a profound impact on me. No longer was I trying to

make soul-less photos with long glass. I was trying to capture

honest, intimate, storytelling moments with a wide angle

lens. At one point, I told Bruce that I wanted to take Sidelines

and make it international. Along the way, it's evolved into

focusing primarily on weird and unique sporting events.

TID:

Regarding the image, how did you hear about it, and

what made you decide to cover it?

SOL:

Man, my memory is horrible. Somehow it had been on my radar

for a couple of years, most likely a tip from a friend. I had seen

some videos online, which showed its potential. I didn't realize

it'd be as great as it was.

An advantage of being freelance is I have tons of free time. So

I loaded up the car and drove down to SF.

Now I never thought I'd have a photo book published from

my weird sports, but that was definitely becoming a goal.

Ironically, this photo is on the cover of my new book, which

was just published by Kehrer Verlag in Germany.

TID:

How do you make the decision that the sport is "weird"

enough to cover? What is your criteria?

SOL:

It's got to be fun. First and foremost. And photogenic. Yeah,

fun and photogenic. And with some level of athleticism and/or

competition. If it's a spin-off of traditional sports, even better.

I know many times folks have looked at my photos and questioned

whether it's a sport or not. That's cool. But what's great about

this being my project is I get to define it and make the final call.

TID:

Lets talk about the image now. Talk about your

mental preparation for this picture.

SOL:

My mental preparation? Try not to fuck it up.

One thing I love about weird sports is that it's usually pretty

photogenic, lots of low-hanging fruit to pick. I'm sure you

could argue that the events I find are more interesting than

the images I make. My goal is to simply capture the feel and

the atmosphere. And not to fuck it up.

I'm also looking for layers, which is a reason why I prefer

using a 35mm f1.4 rather than a 400mm lens. I want more

information, not less. I want more intimacy, not less.

One thing I've learned about making photos is that oftentimes,

if you see a moment, it'll repeat itself, you just need

to watch for it and be ready. I had seen waves upon waves

of dressed-up bikers go down this hill. I chose a spot that

had nice lines and layers. At the bend, folks usually had a

HOLY SHIT!/Come to Jesus moment. It was also near enough

to the starting line that the pack was still pretty dense. I

wanted a congested image full of crazy riders having fun,

perhaps in a mild wipeout. I knew this spot had the potential.

I did move around a bit to mix things up for the 2-3 hours

of racing, but I kept coming back to this spot because I felt

it had what I was looking for.

TID:

What surprised you about this experience?

Well, at first, that anyone showed up. I arrived an hour or

two early and found rock star parking in SF, which never

happens. There was hardly anyone there. The rain was starting

to come down and I was worried that folks might not show up.

A few of the early birds there told me not to worry. And sure

enough, tons of riders dressed in costumes arrived right before

race time.

I was also a little surprised at how many fans showed up. For

an off-the-grid event like this, it had a strong turnout. I know

the organizers were complaining aloud that it was getting too

big - and mainstream. That's what usually happens with

these weird sports: they either blow up or they die on the vine

too quickly. If there's something I want to photograph that

might not last another year, I try to hit it up right away.

Slamball, I'm thinking of you.

TID:

Was there something you wish you had done

that you didn't do?

SOL:

Honestly - and hopefully without sounding arrogant - no.

I'm not saying I couldn't have made better photos. Or done

things differently, because I could have. Over the years,

I've come to peace with the way I shoot photos. I'll miss

things and others will capture better frames. But in order for

me to be the best I can, I can only be myself. That make sense?

A pet peeve of mine has always been picture editors that

say, "You should have shot it this way." or "Too bad you

didn't get this." There are really no rules in photography.

And I look at my photography as an evolution. I may want

to reshoot something because I didn't get what I wanted,

but I don't look at it ever with regret. My only regret would

be not showing up and taking photos in the first place.

TID:

What advice do you have for photographers

who try to carve out their own niche in

photography?

SOL:

There's really only one thing:

Don't take "no" for an answer.

I have 68 images in my book and only 2 were ever

published in print, despite my best efforts. Almost

all of the photos were taken on my own time and dime.

Don't think I haven't pitched being a weird sports

photographer to magazines, because I have. But I

refuse to let any lack of interest from others deter

me from what I want to do.

Back in the day, many folks like myself signed up for

newspapers with the hope of being assigned killer

stories at home and abroad. Budgets and priorities

being what they are today, that's not really feasible.

It's one of the reasons why I left the newspaper world.

I wanted more ownership of my career.

If you start taking photos of what's important to you,

that's all that really matters. Eventually, if you do it

long enough, that's how people will start to identify

you. Being my own assignment editor is pretty cool.

I always say yes to fun photo ops.

TID:

What have you learned about yourself

that you didn't know at the beginning

of your path in photography?

SOL:

It's taken a long time, but I've come to terms with my

unique, random path as a photographer. There's a

misconception that there's a single formula to success.

There's not. All the steps - and missteps - I've made

along the way helped bring me to this point. There is

more that I want from my career, but if I look at what

I have, I'm very thankful.

TID:

You said: "There's a misconception that there's

a single formula to success." I think that's even

more important these days for people to hear.

Can you expand on this?

SOL:

Sure. I'm going to embarrass my good friend Matt Eich,

because he's a great example of what I'm talking about.

I love Eich. I love his work. You can never say enough great

things about Eich. Never.

I think the kid just turned 25.

I've talked with many young photographers who tend to

compare their careers to Eich's. "If he's 25 and killing it,

why am I not taking pictures like that and I'm 30?" (Imagine

if you're 40, like me.) Comments like that are not fair to

anyone involved.

Everyone has a path, a unique path, and life experiences that

drive their passions and pursuits. Some, like Eich, figure

their shit out earlier than others. We don't expect any two

people to be identical. Why would we assume the same

about career paths?

I've met photographers who kill it now who didn't get into

it until after trying other career paths. Former law student,

ambulance driver and forest firefighter turned badass

photographer Matt Slaby is one who comes to mind.

Back in the day, a common experience for editorial

photographers starting out was to 1) go to a college for

photojournalism; 2) intern at a small paper; 3) intern at

a larger paper; 4) graduate and work for a small paper

for 1-2 years; 5) leave your small paper for a larger paper

after 3-5 years; 6) leave that large paper for your dream

newspaper job; 7) retire in your velvet coffin.

One step was supposed to lead to the next step. It didn't

always work that way then, and it's definitely less so now

since all papers are struggling. In many ways, that's exciting

because you can create your own formula to success.

TID:

What have you learned about others?

SOL:

You know, I can really identify with those who do weird

sports. There's no fame or glory in it. They do it strictly

because it's fun and allows them to be silly. That's what

I think photography has afforded me as well, the ability

to have fun and be silly.

TID:

I had a friend look over your interview, and

they asked me to include this question:

"What would be your dream weird sports

assignment, and how would you like to cover it?"

SOL:

Well, what we really need is a Weird Sports Olympics. Two

weeks of nothing but photogenic silliness and all-access

for the press photographers. We could have one for summer

sports, another for winter. Honestly, I'm surprised this hasn't

happened already.

What would really be my dream is to have a regular photo

column for a magazine (I miss others paying my expenses.)

I've already shot a lot of the more celebrated weird sports.

What I'd really like to do is go further off the grid and find

some sporting gems outside of Europe and the U.S. Do you

have any influential people who read this column?

TID:

Thanks, Sol. In conclusion, you recently published

a book of your work, how can people buy it if they're

interested?

SOL:

People interested in the book can go to:

http://www.weirdsports.de/

If folks want to see my latest adventures working on the

next volume of Weird Sports, they can check out my blog at:

http://www.solneelman.com/

++++

Sol Neelman spent from 1997-2007 as a newspaper photojournalist.

The final 7 years were spent documenting his home state as a staffer

for The (Portland) Oregonian. Yep, an Oregonian at The Oregonian. He

has placed in the Pictures of the Year International (POYi) competition

for Best Sports Portfolio and Best Action. His mom is most proud of the

2007 Pulitzer Prize for Breaking News Reporting, which he won with a

team of staffers from The Oregonian for coverage of a missing family

in southern Oregon.

His work has appeared in National Geographic, ESPN the Magazine, Sports

Illustrated, Rolling Stone, People, Newsweek, TIME and The New York Times

among others. Commercial clients include Nike, eBay and ACE Hardware (The

Helpful Place!).

++++

Next week we'll discuss this self-portrait of Ross Taylor and how you,

too, can get into monster shape by just reading The Image, Deconstructed

and eating kale.

It's actually a striking image made by Daniel Kennedy. He'll discuss the

creation of the picture, and how he problem-solved to make it happen.

As always, if you have a suggestion of someone, or an image you

want to know more about, contact Ross Taylor or Logan Mock-Bunting:

ross@imagedeconstructed.com

logan@imagedeconstructed.com

For FAQ about the blog go to:

http://www.imagedeconstructed.com/

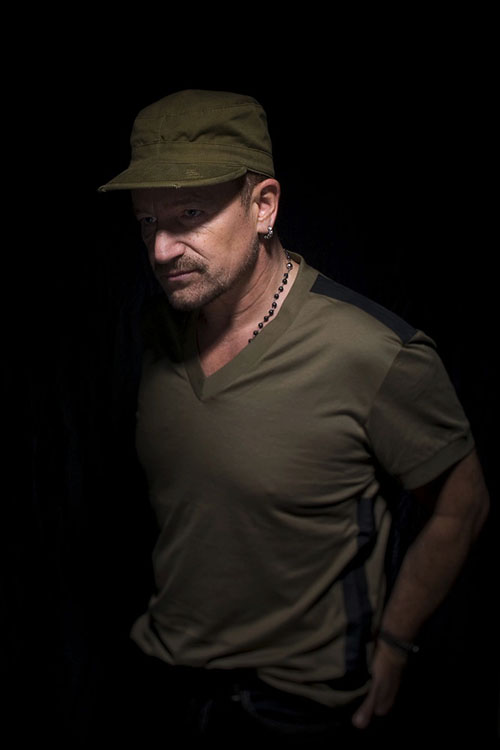

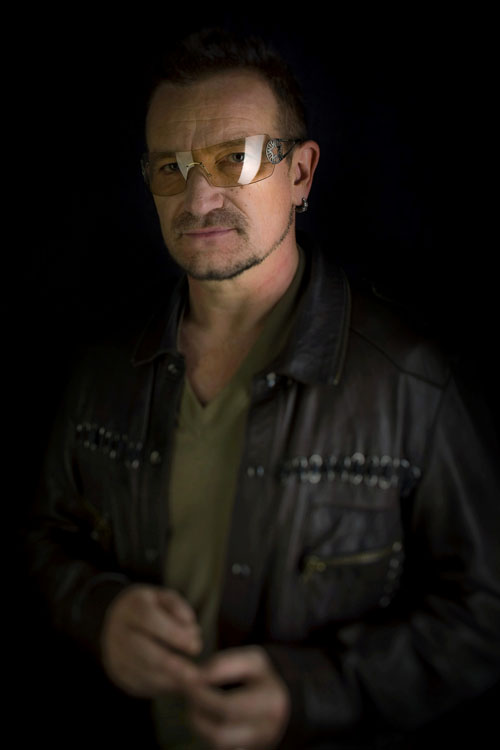

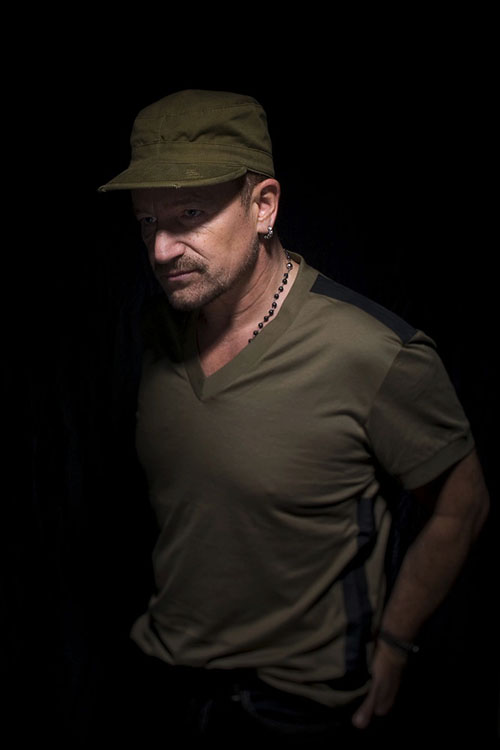

Spotlight on Jay L. Clendenin

TID:

Thanks, Jay, for speaking about this image and your experience.

Please tell us a little bit about your role at your newspaper.

JAY:

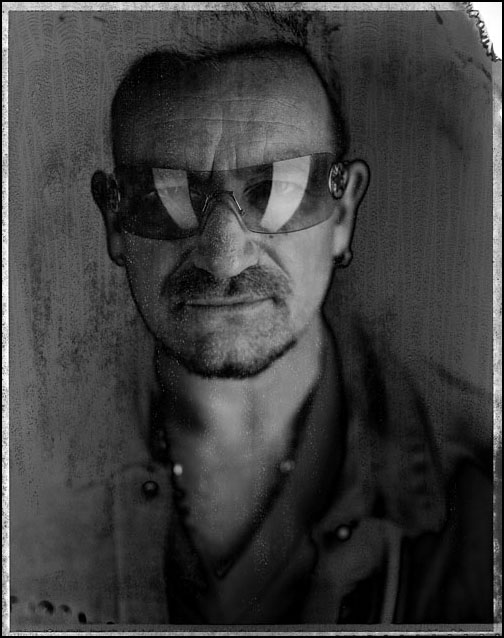

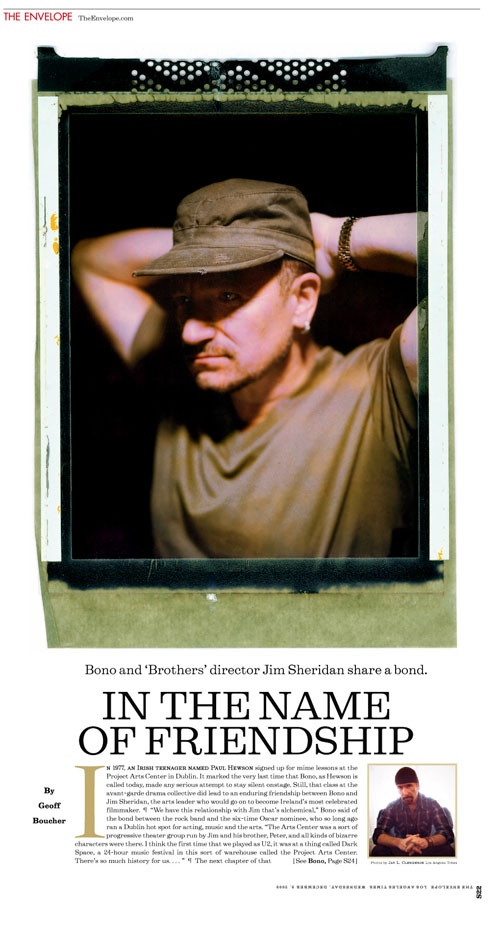

I'm a staff photographer at the L.A. Times, with the majority of

my assignments being portraits and a large number of those

being celebrity portraits. This particular assignment was for a

portrait of U2 front man, Bono, for our award-season insert section

"The Envelope." Bono had written the song "Winter" for the movie

Brothers, and I was tasked with making a cover image, and at least

one other scenario/look for inside. I also have to thank fellow staffer

Liz O. Baylen for NOT being available to shoot this, so that I got the call...

TID:

Before we start talking about the featured image, tell us a little

more about what it's like for you to photograph famous people.

JAY:

It's been a long and winding road BACK to my hometown of L.A.

I always had an affection for Hollywood and the ability to create

illusions - and now that's the majority of the work I do. Portraits

have always been a favorite challenge of mine in photography.

During my time at the Hartford Courant (just under four years), my

first newspaper job after college, I covered everything. It was around

2000 that my editor at the time, Bruce Moyer, re-introduced me to

the 4x5 camera, and encouraged me to take his camera out and shoot

feature section assignments with it. I was hooked.

It made me slow down. No motordrive. I had to interact more with

my subject and direct them. There were very few opportunities for

"found" moments since I had to TELL a subject they couldn't move after

I focused the camera.

I began focusing on portraiture and after leaving the Courant for New

York City, then some time in Washington, D.C. covering politics, I made

it known that I was interested in portrait assignments. When I began

talking to the L.A. Times in the spring of 2007, they were interested

in my feature projects and portraits, which is the majority of what I

shoot now.

TID:

Please tell us how you prepared for the assignment.

JAY:

I approach all my portraits with the same commitment to

not make someone look bad (attempting to take into account

their insecurities or privacy issues), but I will say I am less tolerant

of impatient/rude/demanding "celebrity" subjects than of non-

celebrities. When someone crosses over that line of obscurity and

become "famous," they become a professional in our/their world

(media/pop culture).

When someone from the L.A. Times, or any media outlet, is coming to