This week, TID takes a look at look at the story behind this image:

TID:

TID:Hey Mark, thanks for taking the time to discuss this

image with TID. Can you please describe original assignment?

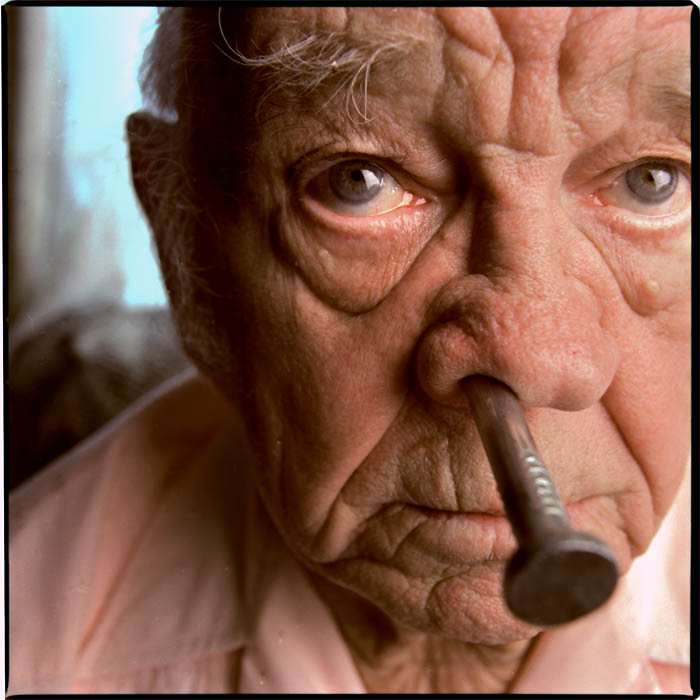

MARK:The picture is from an assignment I had in 1997 when I was

a staff photographer at the Palm Beach Post. The paper wanted

to profile the town of Gibsonton, because a former carny

and accused serial killer, Glen Rogers, was to go on trial for

the murder of a woman named Tina Cribbs.

Gibsonton is a winter home to thousands of carnival workers

and in our story the Post reporter described the town as a

place where, "a carny pays for tires and rims for his truck

with $1300 in quarters."

In addition to the town's transient citizens, it was also the

home of some well-known retired sideshow performers

including Melvin Burkhart, the person in this photograph.

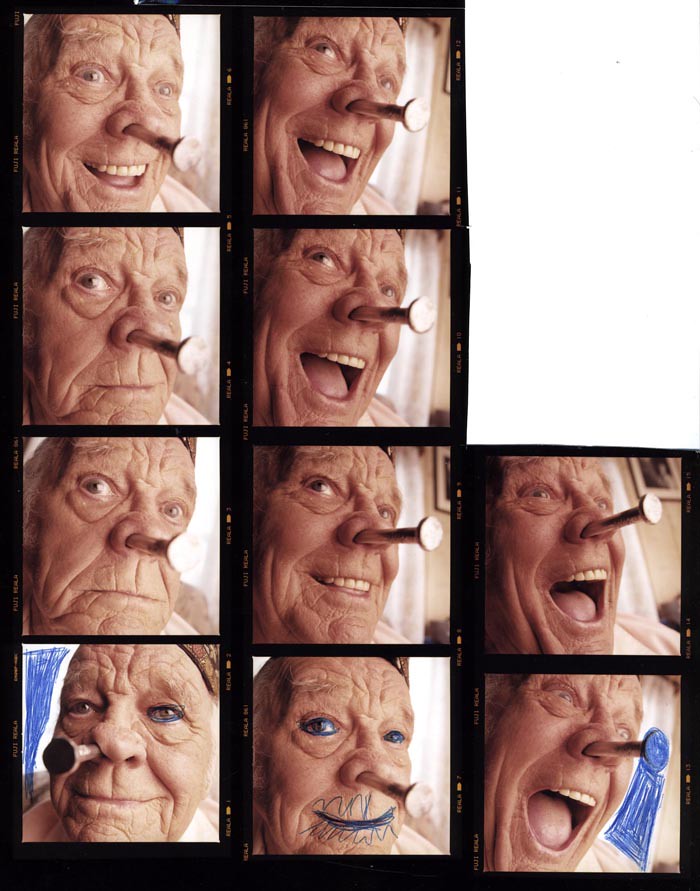

For his ability to drive a nail into his head, Melvin became

known as "The Human Blockhead."

TID:

TID:This image stands out, not just because of it's impact, and it's

unique vision, but in the amount of time it took to set this up.

MARK:The process that led to this photograph was pretty organic.

Paul and I had spent several days in talking with people in Gibsonton,

and Melvin Burkhart was one of our last interviews.

We spoke about the upcoming trial of Glen Rogers, but the majority

of our time was spent listening to Melvin talk about life in the

sideshows as a human oddity.

Melvin's talents went beyond driving nails into his nose. He could

also turn his head 180-degrees, stretch his skin into unnatural

looking contortions and twist his face so it was a half-smile

and half-frown.

In the 1960's, Melvin said "do-gooders" descended upon his

show and closed it, saying 'these poor people are being exploited.'"

"They didn't understand," said Melvin,"That these 'poor people'

had no other way of making a living."

Through our conversation I got the sense that Melvin was a humble

man - a little sad about not working anymore – but, very proud to

have been able to earn his living as an entertainer.

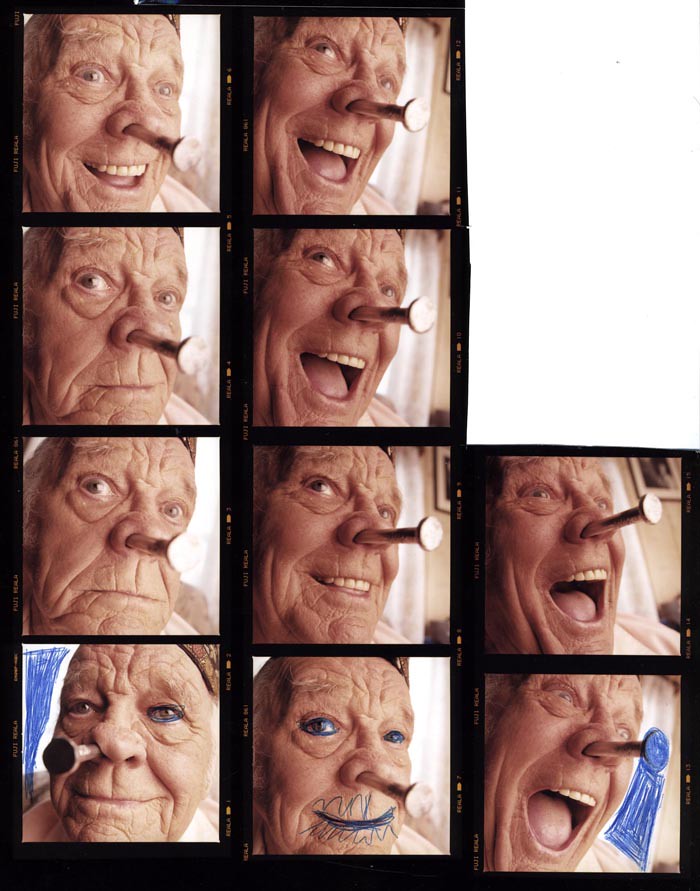

After I asked to make his picture, he took off his shirt and without

getting out of the chair that he had been sitting in during our interview,

started demonstrating how he could contort and stretch his skin.

It was, of course, pretty cool to see his talents but my sense, while making

images of him doing this, was "It's going to be amazing to see what he

does with a nail."

TID:What was his reaction when you brought the idea up?

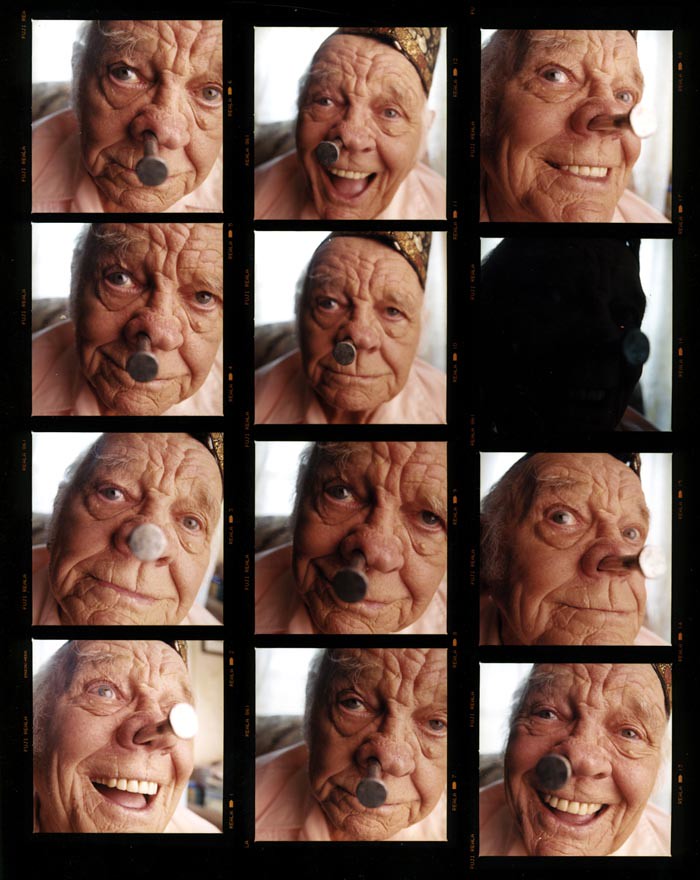

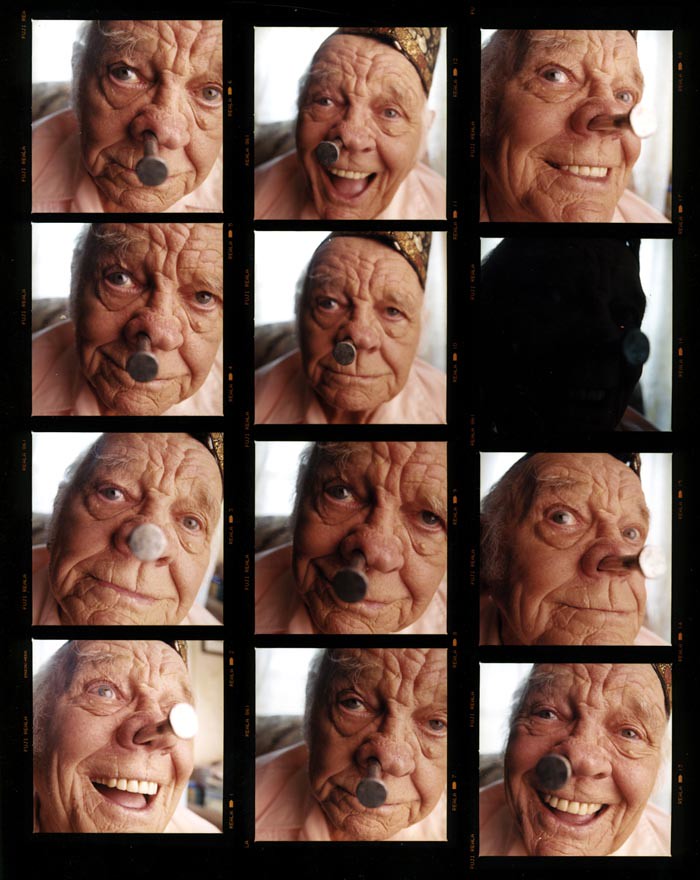

MARK:I think Melvin was open to being photographed in a range of

situations. He was an entertainer, and I felt he was happy, in a

way, to perform again. Also, until you asked about the image,

and I went back to look at the contact sheets, I had forgotten

how much Melvin performed for the camera in so many frames.

I remember that I didn't direct him too much but just let him

perform and waited for a quiet moment. I used the early frames,

with him stretching and contorting, to learn about how he

responded to being photographed.

TID:Was there any point of conflict in this shoot, a moment when he

didn't want to go along with your thought?

MARKIf there was any tension in the process of making this picture it was in

waiting for him to let go of his desire to perform. I also checked with him

to see how long he would be comfortable with a nail in his nose.

TID:What was the format you chose for this image ?

MARK:The format was Hassleblad 6cm x 6cm, a wide angle lens and

a macro tube. I also used a soft box with an amber gel. It was s

omething I used a lot back then. Warm gel foreground, with a

blue-gelled background. Back then, in the mid-'90's, I also used

medium format for portraits as often as I could because I liked

how the camera's precise optics revealed detail in people's faces.

TID:

TID:What did you learn from making this image that you didn't before?

MARK:That's an interesting question, and I would love to be a

mountaintop guru able tell you that through the making

of this photograph some great truth was revealed.

The thing is, though, I think every picture we make is informed

and shaped in some way through the photographs we have made

or seen previously.

Regarding this photograph, it was made after I learned (through

Scott Wiseman) that the white underneath a person's pupil helped

attract a viewer to a subject's eyes. I learned (through the photographs

of Eugene Richards) that getting physically close to a subject

resulted in photographs I found to be more engaging. I also learned

(through other photographers) that wide angle Hassleblad lenses

needed a macro tube to get very close to a person's face.

And through my own dumb luck, I had also learned that amber gels

brought out interesting skin tones. Each of those items appears in the

photograph because I had learned or experienced it through the making

of another photograph.

When I look at the photograph now, I see details, that were in that

image because of things revealed through the experience of making

other photographs.

Until you asked Ross, I really hadn't thought of it quite so objectively

so thanks for asking, again, it's an interesting question.

TID:What advice do you have, for photographers, to make images that provide insight to people's character?

Mark:Listen.

++++

Mark Mirko has been a staff photographer at the Hartford

Courant since 2000. For the ten years prior he was on staff at

The Palm Beach Post.

Mark's work has been recognized by the NPPA, the Pictures of

the Year competition and the Society for News Design. The National

Press Photographer's Association has twice named him a regional

photographer of the year and in 1993 the Post photography staff

was a Pulitzer Prize finalist for its coverage of Hurricane Andrew.

He has an MA from Ohio University and in 2003/2004 was the

Knight Fellow for Newsroom Graphics Management at the Ohio

University School of Visual Communication.

http://www.markmirko.com/

http://passing-time.markmirko.com/++++

We've added a FAQ on TID. To learn more about TID

please go here:

http://imagedeconstructedfaq.blogspot.com/

Next week on TID, we'll take a look at pyschology of the

construction of making this image: