Lisa, we're excited to feature an image from your

Sam Houston High School project.

This was part of a large body of work that was a finalist

for POY's Community Awareness Award. Can you tell us

about the project and how it got started?

LISA:

The proposal for the project was put into motion when Sam

Houston High School was placed on the school closure list

by the San Antonio Independent School District. Facing the

loss of the only high school in San Antonio’s predominantly

African-American East Side, the community rose up and

loudly opposed the decision. I started the project not knowing

if I was documenting the last year at a school with a 58-year

history or a year of a school in transition, struggling to turn

itself around and lose the stigma of a failing school. The

original access was granted by the new principal and arranged

by the orginal reporter (who left the paper before we started

the project) and my photo editor, Anita Baca, since I was out

of town as the meetings took place.

TID:

How long did you work on this project?

LISA:

After meetings with administrators, the public information

officers and school faculty, all access issues were figured out

by October 2009, but I wasn’t able to start photographing until

mid-October because of previous commitments. Basically I had

from mid-October until early June. Graduation was on June 6

and it ran that Sunday and Monday. The picture you chose for

TID, I made at the end of my first week of really trying to

immerse at the school.

TID:

Can you talk about how you worked to gain access?

I had almost complete access to the school in terms of being

able to walk in the door and into any classroom. But the

access to the real moments and the students’ lives was what

I had to come up with on my own. And of course that was

the tough part, especially with teenagers who think you are

there to portray their school in a negative light. They really

didn’t know why I was there except their school was being

scrutinized and possibly shut down. I explained over and

over but with 750 students, I was still meeting them and

explaining what I was doing through the school year.

I started out the project photographing the football team

because the coach and the players were very open, and it

was an opportunity to get to know them and sit in the stands,

meeting students and parents in a less structured setting.

Also one of the biggest reasons I followed the football team

was I could go after my shift. I work 7-4 Friday and 8-5

Saturday, so I could almost always get on their bus and could

always make it to the game and not worry about getting called

to go to a last minute assignment or news. The players ignored

me and accepted me so it seemed normal for me to photograph

them at school too which morphed into the other students being

more accepting. Following the football team turned into a section

for the online presentation that didn’t have much to do with

sports, it was about the coaches serving as surrogate fathers to

boys who didn’t have positive male role models in their lives. It’s

one of my favorite parts.

I always sat down with students, asked them questions, listened to

their stories. I talked to them about how to tell their stories. Some

understood, some didn’t. It was a ton of following up with them,

lots of texting, especially for photographing them outside of school.

Access even to the very end was an evolving process. I always felt

at risk of losing the access I had. Teenagers are so aware of the

camera these days and they were very aware of the negative

perception of their school and their neighborhood. They were

very protective of how I would portray their school. That made

it a challenge to photograph some of the more difficult moments

and stories because the students would react to that and tell me,

“You are just going to make us look bad,” or “Miss, don’t take a

picture of that.”

So to counteract that, I went to everything I was invited to. Every

band concert, every awards ceremony, everything positive to show

I wasn’t there only for the negative, which I hoped would allow me

a little more leeway to photograph the “negative.” I thought that

tactic would work better than it did, but I do think it was very

important to do in the long run. And I got to know, and love, more

kids by going to so many of their activities.

TID:

You made the bulk of the images in between assignments

and on your own time. Can you tell us how you managed to

balance the project with your work and your personal life?

LISA:

Personal life? What’s that? I have to admit I didn’t do much

outside of work between daily assignments, other stories that

I worked on throughout the 9 months, and Sam. I didn’t even

exercise much, which is really important to me but when faced

with the decision to photograph after school/after my shift, I

couldn’t say exercise was more important. In hindsight, keeping

my life more balanced would have cleared my head and helped

the project. It’s hard to see that when you are so immersed. I

felt like I had such a small amount of time to tell such a big,

multi-layered story that had so much potential so I put a lot

on hold, including the important relationships in my life. My

family and friends were extremely understanding and supportive

though.

TID:

Was there any moments of conflict, or times when people didn't

want you to take pictures? If so, how did you handle it?

LISA:

There were many moments of conflict when people didn’t want

me to take pictures. Many students thought I would make them

look bad - their perception of media coverage for their school

and neighborhood was largely negative. When I would raise my

camera to photograph tense moments, the students would ask

me not to photograph. Once, a girl starting punching a boy in

the head and it had to do with me. They were joking about who

I should be photographing and next thing I know she’s punching

him. So, do I take the picture of something my presence actually

caused? After a moment I decided to take the picture, raised my

camera and effectively she stopped. In the process, I upset the

other students. That was kind of a constant battle, at least in

my head, how far to push in that regard.

As I’ve described, many a click of the shutter felt like it could

turn the students against me. I had to stay focused on why I

was there, that I wasn’t a good journalist if I didn’t show every

side. I wanted to tell their story as purely as possible, with

balance and fairness.

I’ve made a habit of being focused on light and color as a

storytelling element, but there I couldn’t. Florescent lights,

school uniforms of white, orange or green polos and khaki

pants. I had to focus on moments, and I’m glad because that

was the way I think this story had to be told. I was completely

focused on the moments, the interaction, something I feel

photojournalism often loses in the quest for “style” and “vision.”

I say this because I’ve been lost in that quest myself at times

in my career, as we are hopefully constantly evolving in our

development as visual storytellers.

The project was truly an emotional roller coaster. I wrote about

this in the NPPA article - I noticed I didn’t listen to the radio anymore.

I really didn’t care about anything else, all I could think about was

their stories, and how to tell their stories. I’m already pretty focused

and obsessed when I’m working on a project, so I’m sure I was not

too much fun to be around during this process.

TID:

Now, to the image. Can you give us some insight?

LISA:

I had been hanging out with the students on the left since I

arrived at the homecoming dance. They were gathered

outside and a couple I had recently met were being affectionate

so I was trying to capture that. It was also a really diverse

group so it was a good opportunity to try to tell that part of the

story. I walked into the dance with them and continued to watch

them. Honestly, I don’t remember my exact thinking at that

moment, except I had been watching them. I somehow noticed

the girl dancing near them and anticipated her dancing by. As

you can see, they weren’t paying any attention to her at first. I

don’t remember if I even saw what her shirt said. I’m

embarrassingly inattentive to some details. It was a pretty

simple situation.

TID:

In situations like a high school dance, people are often

very aware of a photographers presence, and yet you seem

to be able to blend in very well. Can you tell us how you achieve

this?

LISA:

I really don’t know how I achieve this. I feel somehow I am easily

ignored by most people I photograph. I have no idea why or how.

I’m sure this happens with most photojournalists or we wouldn’t be

able to do our jobs but I am always amazed at the situations I walk

into and start to photograph and nobody pays me any mind.

TID:

You've worked on numerous long-term stories. Can you

tell us your motivation behind this type of work?

LISA:

The whole reason I want to be a photojournalist is to bring greater

understanding to issues and people’s lives, to educate viewers about

people, places, things they would otherwise not know about, or might

turn a blind eye to. A long term project has so many layers and is

always growing. It can bring depth to a story and people in a way

rarely found within a daily assignment. To me, a story should be told

in layers, with each photograph building upon the next to tell the story

in the truest way, with an ebb and flow of emotions and situations.

The kind of photographer I am is both a blessing and a curse, because

I always think there is a better picture to be made if I just wait long

enough for the moment. I think the light, the composition, if I keep trying

to make it better, that it will be better. I despise the phrase, “good enough,”

because I feel I can and should always do better. So this is especially

applicable to a long term story, because you can tell the story in a

much more complete way.

TID:

Thanks for all your insight Lisa, one final question. Do you have

advice for photographers who want to work on community-type

stories that span over long periods of time?

LISA:

Time is everything, tons of time. The time you put in equals

access, comfort level and our ultimate goal, becoming part of

the scene so life goes on as if you aren’t there. I think showing

the people who’s story you are trying to tell how committed

you are goes a long way in their openness to you. Above all

you must be committed and self-motivated. You can’t expect

anyone else to push you or stay on top of what you are doing.

Most newspaper editors are too busy to deal with long-term

projects on a regular basis.

With a community story, there are many layers and many stories

within the bigger story. It takes listening to people a lot and

engaging them to find out their stories. Sometimes their stories

are the ones you want to tell, sometimes their stories lead to

other stories. Within every situation I’m in, I’m looking for the

next story, the next situation I want to put myself in where I can

make pictures that will tell the story I’m trying to tell.

Stay organized (although I am incapable of following this advice).

Organize names and phone numbers, and try to use the same

notebooks for the story. Stay on top of the editing. Get an editor,

mentor, teacher, trusted friend, etc. to give you feedback throughout.

+++++

Lisa Krantz is a staff photographer at the San Antonio Express-News. She joined the Express-News in 2004 after working at the Naples (FL) Daily News for five years. She received a psychology degree from Florida State University and earned her master’s degree in photography from Syracuse University.

At the Express-News she covers everything from hurricanes to the NBA Championship but her true love is finding and telling intimate, untold stories in her community. She is a three-time NPPA Region 8 Photographer of the Year, in 2005, 2009 and 2010, for a diverse array of assignments and long-term projects.

In 2011, Lisa was awarded third place Newspaper Photographer of the Year in POYi. Her project chronicling a year at Sam Houston High School, a troubled school threatened with closure, was also awarded second place Issue Reporting Picture Story and named a finalist for the Community Awareness Award in POYi. The project was part of the portfolio that earned Lisa the 2010 Scripps Howard Foundation National Journalism Award for Photojournalism and was named a finalist for the ASNE Community Photojournalism Award.

You can view her work at:

http://www.lisakrantz.com/

Sam multimedia:

http://www.mysanantonio.com/news/education/item/Sam-Houston-High-School-Video-Container-3633.php/

+++++

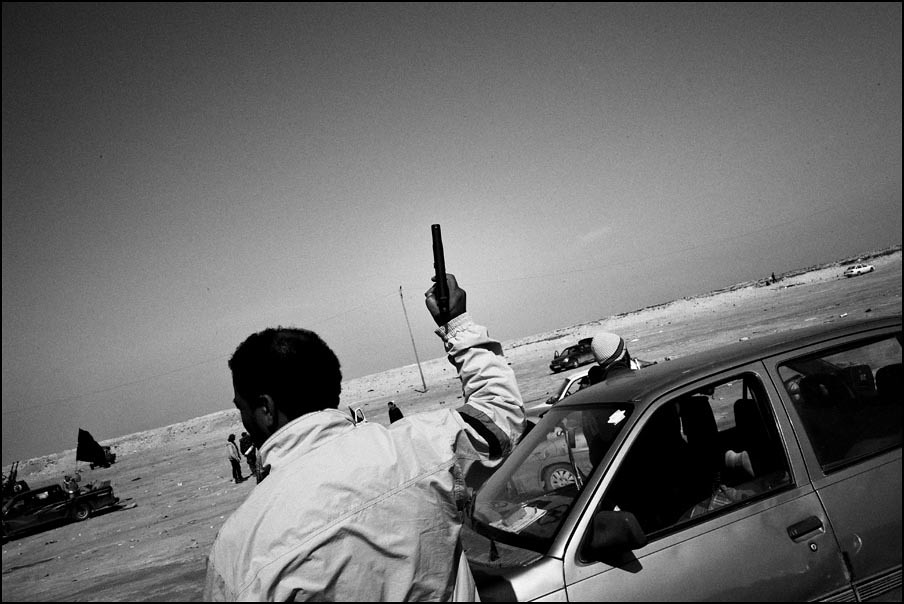

Next week on TID, we'll take a look behind this image from Lexey Swall:

As always, if you have a suggestion of someone, or an image you

want to know more about, contact Ross Taylor at: ross_taylor@hotmail.com.

For FAQ about the blog see here:

http://imagedeconstructedfaq.blogspot.com/