Daniel, thanks for your willingness to talk about this image.

Please tell us some about what this image is, and why you made it.

DANIEL:

Ross, it's an honor to have my image on this blog along side such

talented photographers. Thank you!

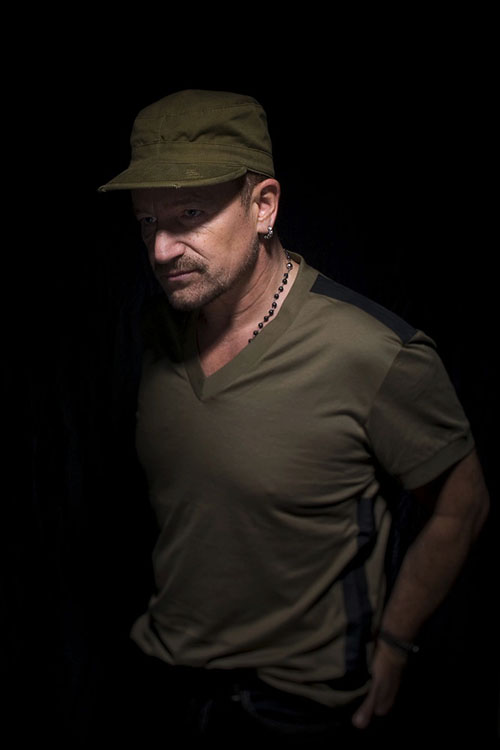

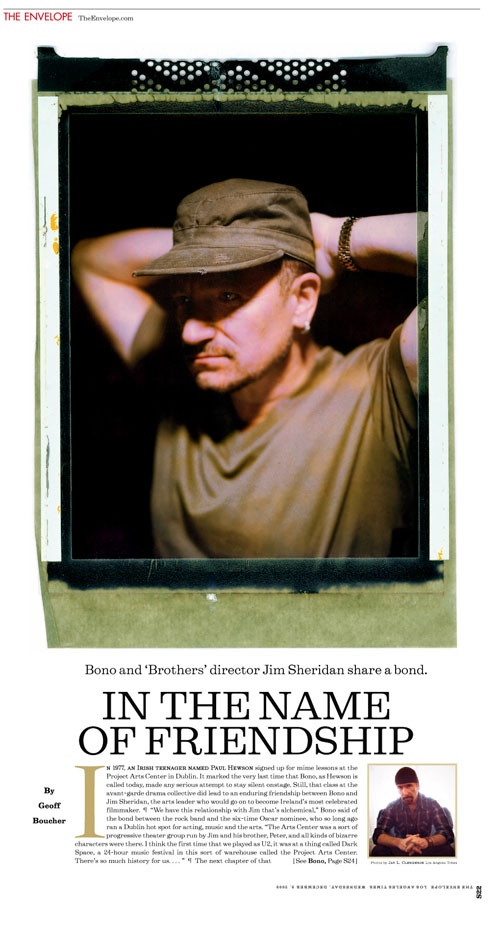

Joe Phillips, an aspiring actor and friend, hired my business partner and I,

Nicole Truax, to do a character shoot for his portfolio. Instead of the usual

straightforward headshot, we opted to go all out for a full character study.

This better shows the actor's potential to portray a certain look. Character

shoots offer actors the ability to create a body of work in a short

period of time that they can then pair with their film work to show

greater versatility; something very valuable in the entertainment industry.

So… a bottle of lighter fluid, several arrows, a bow, and 36 military-grade

smoke grenades later this is what we came up with. One of Joe's

skill sets is archery; he also has a British accent. So creating the

character of a warrior/archer was something that came natural, and

also a role he would enjoy playing.

TID:

We're going to include a number of images from the shoot to give

people an idea of how this developed. It's interesting to hear your

thoughts, though, from the beginning. Can you talk about how you

mentally prepared for this?

DANIEL:

The idea for this started off very simple. Joe needed a shoot, and he

gave us a list of looks that he wanted. Nicole and I began to talk

about what we wanted and the first idea was very simple: take Joe

up a mountain and photograph him with a bow and arrow. At some

point Nicole said, "I wish we could light the arrow on fire."

"Well why can't we?" I said. "I know a way to rip up a shirt, tie it in a ball,

and light it on fire so it burns for a long time but burns relatively cool so

it's not dangerous."

"Really?" she asked me. "Let's do that," she said.

Then, of course, once we had a flaming arrow involved, we wanted to

put him in a swamp, make a ton of smoke, cover him with muck, and

give him a giant knife. I mean, isn't that the obvious progression of

thoughts? One thing may not have worked without the other, but with

everything together it becomes "cinematic." That is, as long as you get the

lighting and atmosphere right. I think we get bored easily and always

want to do something exciting and different. So it's natural for us to

get inspired by something and run with it.

To prepare, we also looked through thousands of photos and drawings

of warriors/archers on the Internet, and could barely find anything that

really helped. Often we make a folder of images that inspire us that we

find online. This usually helps give us an idea of good ways to light a

certain subject. Obviously we don't copy the images, but it helps to see

how other photographers have solved similar problems and it gets your

own mental gears turning. There was a serious lack of high quality

"Warrior/Archer photography." I wonder why? Maybe we can fill that void.

For the location we chose to meet at my parents' house in upstate New

York (about an hour and a half away from Nicole and I, a three hour trip for

Joe, and an hour trip for Colin, who also helped.) This was the best place I

could think of that we would have access to, and not get arrested. My

parents own three acres, and there are miles of woods behind their house.

Colin (a long-time friend/Army captain/weapons specialist) and I had played

paintball throughout high school in those woods and I immediately thought

of a swampy area for the location. I knew we had to do it there. We had

staged our own battles there for years, it just made sense to go back there.

It's weird, creatively I always find myself going back to shoot at strange

places I've been. It just seems right. If you visit enough areas, eventually

you'll have somewhere to go for anything I suppose.

TID:

Once you began the shoot, can you walk us through the next step?

DANIEL:

Basically, we first had Joe walk around wearing a green shirt and we lit

an arrow on fire to add drama. At first the photos didn't look believable to

me, they looked more like we were "pretending." I was worried that the

photos wouldn't resonate the way I wanted them to. I'm sure every

photographer can relate to starting a shoot you're really excited and anxious

about, and looking down at your first images on your camera's LED screen

and having a mini panic attack because everything just looks wrong --

nothing like you had imagined them to look in your head.

TID:

I'm a big fan of problem solving, so in this case, how did you

solve the problem of “pretending?"

DANIEL:

It looked like "pretending" because 1) that's what we were doing, and 2)

we didn't have the lighting figured out yet. Lighting is everything. So we

decided to see how things looked out in a more open, swampy area with

more sunlight pouring in. I had Colin McNulty assist with the shoot, and

you can see him placing some smoke grenades in one of the images.

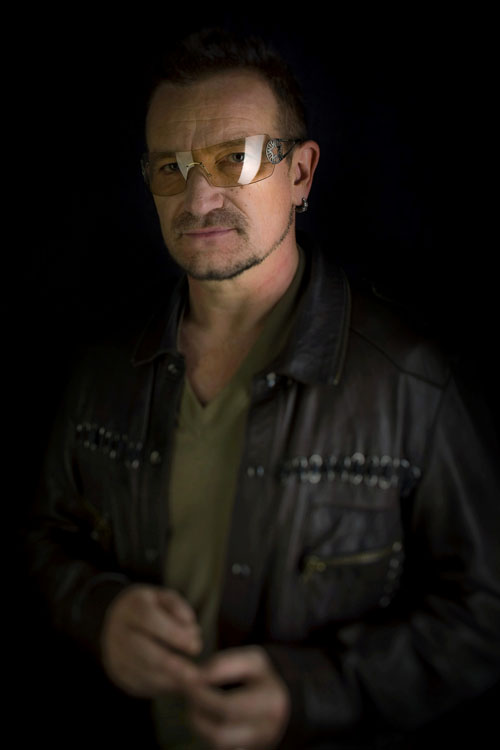

I had Colin set off smoke grenades while I would shoot and relight the arrow

with Kerosene. Nicole and I often switch back and forth while shooting,

one working lighting and talking to the client while the other shoots. This

helps because when you're working lighting you're often closer to the subject

and can notice certain things that you might not from behind the camera and

vice/versa. I had started shooting in the woods, then had Nicole shoot in the

swamp at first. I handed off the camera to her and started to use an umbrella

to create diffused side lighting. After some trial and error, we moved back

into the woods and Nicole suggested we use side/back lighting with a bare

flash. This is where we finally got the lighting the way we wanted. I also had

a better understanding of how the light effected the smoke because I could

see it happening up close. Something I wouldn't have arrived at if we didn't

switch spots and jobs.

One of the major problems was with lighting the smoke. We had to figure

out an angle to illuminate the smoke without blowing it out, so we couldn't

have the light source in front or else it looked too fake. Again, we had to

overcome this to make the scene work.

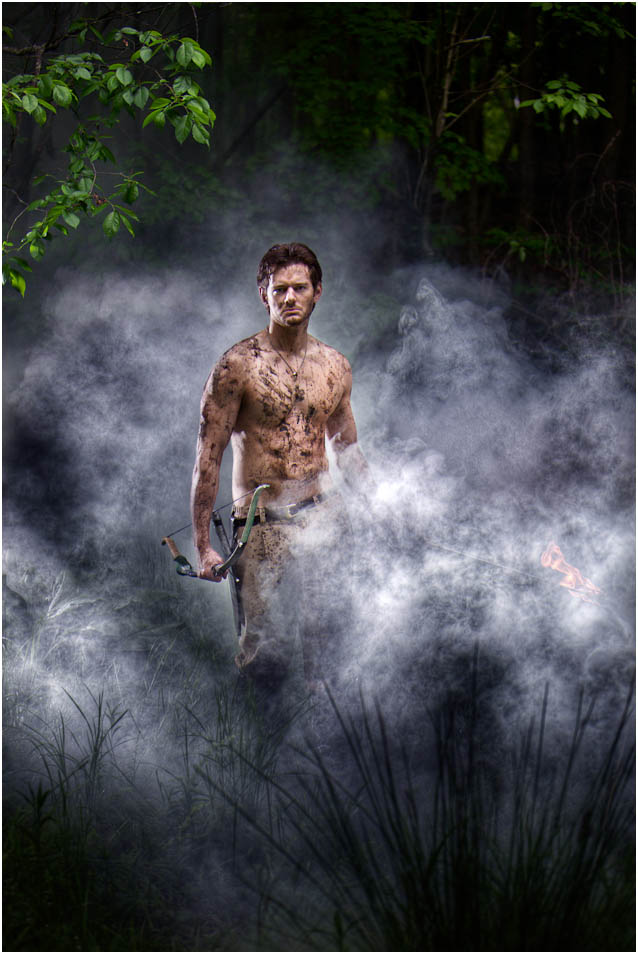

The image became more believable at this point. We asked Joe to lose the

shirt and dirtied him up with mud and water; this made him look more like

a warrior and less the part of the actor playing the warrior. At the beginning

of the shoot, the shots kept reminding me of B movie stills and I hated them.

Everything changed once we got the lighting figured out (how to illuminate

Joe dramatically while also illuminating the smoke so it didn't become too

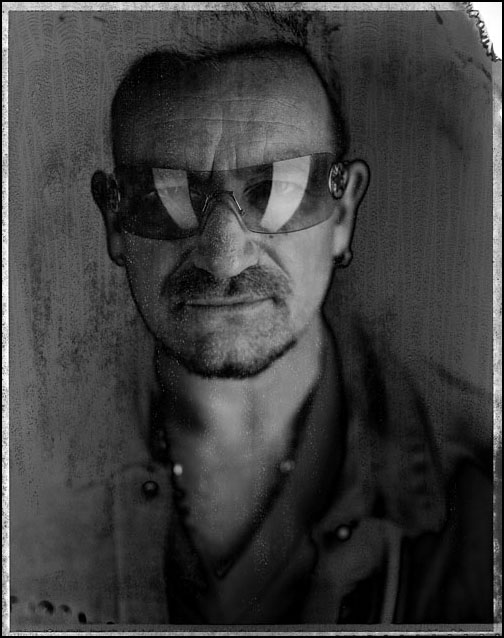

bright or dark.) We decided to move back into the swamp area and use the

same lighting techniques we had figured out while using more smoke grenades.

I crouched low and had Joe walk towards me while Colin set off more smoke

grenades in locations both up and down wind. I had him repeat this walk

several times to get different looks. Nicole walked slightly behind him while

he walked so the light source moved with him. The main image being

featured in this post happened at that time. This is where everything really

fell into place. At this point Joe was covered in mud, wet, relaxed and

shirtless in 40-degree weather. I think he finally felt the part.

Nicole and I would often stop to look at the photos on the screen and

collaborate on lighting, angle and composition. This is usually how we

work, passing the camera back and forth, throwing new ideas to each other.

TID:

You said you collaborated with Nicole on this shoot. In what ways do

you collaborate mentally?

DANIEL:

Nicole and I collaborate on every project. It's one thing that I think has

led so much to our growth. With two minds working on something it's

always easier to keep things fresh. We both have a similar view of what we

think looks good and our style has evolved together. Prior to the shoot, we

often bounce ideas off of each other, and are very honest if we think

something won't work.

The fact that we are both equal photographers in the business also helps

when managing people during a shoot. Sometimes as an assistant you

aren't really even allowed to interact with the clients. When we work

together we feel completely comfortable directing/talking to the subject

while the other person is focusing on technical aspects. So instead of just

having to isolate yourself for a minute in thought, which can be awkward

for a subject, one of us can always take point. In short, we do everything

as a team. I've worked with other photographers, and there's never the

same synchronicity unless it's with Nicole.

TID:

One of the reasons I admire this image so much is that too often we wait for

someone to give us an opportunity to be creative, or conversely, critique

others for our lack of opportunity. Can you tell us how old you are and how

long you've been shooting? I think it's insightful for people to know this.

DANIEL:

I'm 24, Nicole will be 24 this week. I started shooting in fall of 2006 when

I took my first B&W photography class at the Hartford Art School. Nicole

has been taking classes since she was very young; she was actually eight when

she took her first photo darkroom class. Professionally we have been

shooting since May of 2009, the month we graduated from college. We tried

to find jobs in the photography world, and actually applied to more than 300

of them in a four month period, went on two interviews, but were rejected due

to lack of experience. So since we couldn't find anything else, and rejected the

idea of finding a job in any other field, we started our own business in

September of '09, Linked Ring Photography. We've both interned for other

photographers, but came to the realization that you learn a lot more from

doing than watching.

For Joe's shoot, it really started out as simple head shots, which he's hired us

to do in the past. But as we sat and thought about it, we wanted to make this

particular shoot different. Take it to the next level. Something we could all

be proud of. When we shoot a job the way we've seen other people

do it, it just doesn't stand out as much to us. When we go the extra mile to

make something "crazy," it stands out.

TID:

What were some other problems you faced, and how did

you deal with them?

DANIEL:

As with any shoot, nothing works perfectly. The first problem was we

didn't have a generator or external power for our strobes. Our 500+ feet

of extension cord was short by 100 ft of where we wanted to shoot. So

we opted to use external flashes, which we would have eventually used

anyway due to their mobility and what we needed the light for.

It was raining on and off. Thunderstorms were set to come in during

the early afternoon so we had to shoot in the morning, both for light

and safety.

It was cold, there was poison ivy everywhere, and Joe had only slept three

hours the night before in order to travel for the shoot.

Smoke grenades are extremely difficult to control as the wind changes, etc.

Apparently it's not, "Hey, let's light an arrow on fire and throw some smoke

grenades and everything will be great." It's "Oh my God, how are we going

to do this now that everyone is suffocating and we can't see?" I'm exaggerating,

but it was a learning process and we literally used about 25 grenades

before we understood the wind currents, the way the light would interact

with them, as well as where Joe needed to be.

TID:

What did you learn about yourself during the making of the image?

DANIEL:

That in order to be as good as we want to be, we need to treat all shoots

like this. We need to always use our creativity and put in that extra

mile to make things complete. We need to put an emphasis on concept,

location, and props.

TID:

In the end, what did you take away from this experience,

and what advice do you have for photographers?

DANIEL:

Don't settle or cut corners to make something easier. Being a photographer

is hard. You owe it to yourself, and the people who believe enough in you to

pay you, to do everything you can to make your work the best it can be.

++++

Linked Ring Photography is a Greenwich, CT based commercial photography studio that consists of Hartford Art School graduates Nicole Truax and Daniel M. Kennedy. Like the original members of the Linked Ring Brotherhood, we believe that photography in itself is capable of the highest forms of art. Our mission is to create a new and exciting experience in each and every project through our concept-driven ideas and lighting techniques.

www.linkedringphotography.com/

++++

Next week we'll learn what happens when dogs attack, take over

the world, force us to wear cones and play fetch.

It's actually an image by Matt Roth, who specializes in creative portraiture.

I really love his work and he'll offer a lot of wonderful insight.

As always, if you have a suggestion of someone, or an image you

want to know more about, contact Ross Taylor or Logan Mock-Bunting:

ross@imagedeconstructed.com

logan@imagedeconstructed.com

For FAQ about the blog go to:

http://www.imagedeconstructed.com/