We've picked a picture from a photo story you did

on your mother, who sadly, died of cancer. Can you

talk about your decision to document your mother?

LOGAN:

I have to start out by saying I think it is interesting

that you chose this topic, and this image. Today is

exactly three years since she died. And as for this image,

I've recently decided to use it with another image from

this series to go into a book project of this story.

But to get to your question, we have to go back a little bit.

Mom was a very strong supporter of my photography and

journalism; she was also a visual and creative person.

Before she was sick, we would talk for hours about story

and image ideas. I still have two notebooks of our ideas on

my bookshelf.

Ross, you and I have talked many times about how important

it is for the photographer to express their wants and needs to

a subject, so roadblocks don't come up at emotional times during

the story. Explaining expectations for access can very important

in this process. Mom completely understood this concept. She

totally "got" why I would need to be in places and witnessing

events at precise, and sometimes uncomfortable, moments. Not

only did she understand, but she would make suggestions.

That's how the story started.

Mom called me a few years ago and asked me to come over -

she told me to bring my camera. I'd been freelancing for about

2 years, and like I said, she loved to share thoughts about

imagery. I figured it was probably another idea, or maybe a

pretty flower in the garden that she wanted a picture of.

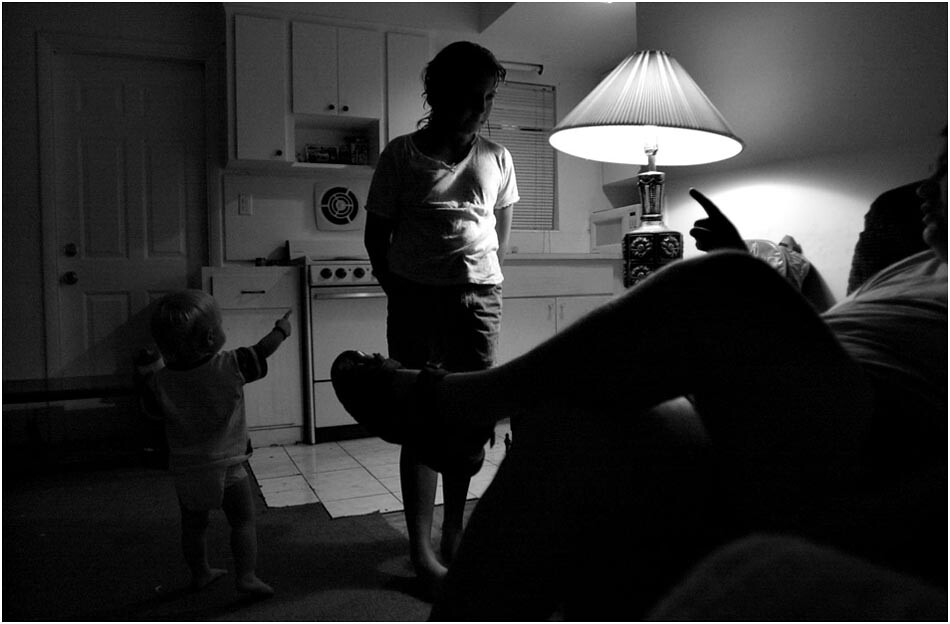

Instead, that afternoon she told and me and Dad that she had

a tumor in her lung.

I was surprised, but as she began to explain more, it clicked

what was going on, why she specifically asked me to bring the

camera, and I took this image of her talking to Dad:

Later, she asked if I wanted to photograph her journey. She

didn't want to call it a battle or a fight - those words were too

violent for her. She considered it a journey because she wanted

to survive, as well as embrace the joy of life with what time she

had. But she had obviously thought about me doing a project on

this process before she first called me to come over and talk

about the initial tumor.

TID:

Can you tell us what was going through your mind

while making these images?

LOGAN:

I've had other people ask about what was it like to make

these pictures, and I'm still not really sure what to say.

Obviously, it was really difficult to watch my mother and

family go through this. Sometimes it was difficult to hit

the shutter when it felt like I should be more in the "Son"

role than the "Documenting" role.

There were times I didn't make a photo because it didn't feel

right. Sometimes the only way I got through situations

without completely losing it was being able to put the

camera over my face like a mask, look through a barrier

and think about light and composition instead of what

was going on to my family around me. It ran the spectrum

of all kinds of emotions.

TID:

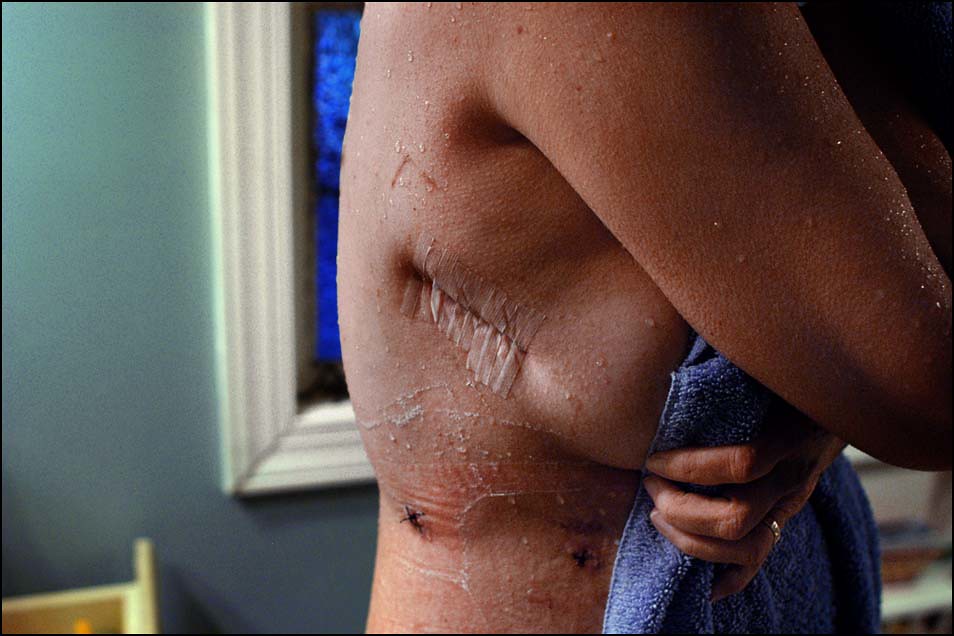

This image is one that is intensely intimate. I don't think I

could make this image of my mother, and I was struck by

the comfort level your mother seems to have with you.

Can you please talk to us about your approach to making

this specific image ?

LOGAN:

I was spending a lot of time with Mom and Dad. I'm a

freelancer, and I made it a priority to be with them. One

day, Mom went to take her first shower after her first

surgery (because of the stitches and bandages, she wasn't

allowed to shower for a time). She literally opened the

bathroom door and said, "Hey Logan, you want to see

my scars?" and then she continued drying off. I grabbed

my camera and made a few images. So that was the

logistical series of events - because of conversations

we'd had before, she knew what types of situations were

of interest and kept me updated on them.

As for the thought process involved, and emotions... I

have to admit, I was a little uncomfortable. I mean, in

our society, it is not normal for a 20-something male to

be in a small room with his naked mother. That just

sounds so ridiculous. And it was a little shocking to me;

I would have never suggested it.

But honestly, I think that shock is what got me through it.

I tend to over-think things WAY too much. And in this

situation, heading into the bathroom, I was thinking about

all kinds of concepts: how the water/bathing was symbolic

of a baptism/rebirth, how the scars were the first outward

sign of her disease (she had no symptoms before being

diagnosed - the tumor was spotted first while doctors were

doing imaging on her heart), and all these heavy metaphors.

Then *BAM*, there is Mom revealed - naked, just like THAT,

and I had stop thinking and react - just make the image that

was there in front of me.

TID:

At any point was there any conflict, any hesitation on your

mom's (or your) part during the documentation? If so, how

was it handled?

LOGAN:

There certainly were times that I hesitated or didn't make

images. Even though I had both her blessing and the rest

of the family knew what I was doing, there were many

emotional and vulnerable moment where I wasn't sure it

was appropriate to take photos. One time that stands out

is when a Niece saw Mom for the last time. It was obvious

that it would be the final time they would speak, and as the

niece left, she broke down weeping. For whatever reason, I

didn't feel right hitting the shutter at that time, so I didn't. I

hugged and tried to comfort my cousin.

I don't think there is a hard and fast rule here. I've heard some

folks say "it is better to take an image and not use it, then want

it later and not have it." That can be true sometimes, but I think

trust is the most important part. Trust and truth. You have to stay

true to yourself. A serious project may push you, push what you

are comfortable with, and that's OK. Growth spurts are

uncomfortable; physically, mentally and artistically. I think you

have to keep yourself open to pushing. But pushing isn't betraying -

yourself or those you are photographing. There were times the

folks in front of the camera wouldn't have cared if I made a photo,

but it wasn't ok with me. So I didn't hit the shutter. Each

photographer has to find that place within each story, each situation.

One of my motivations FOR hitting the shutter was that I simply

didn't want to do Mom and her story a disservice; she had granted

me this privilege, and I didn't want to squander it, let it go to

waste because I was uncomfortable. It made me step up and be

active in circumstances I would have rather shed away from.

That's what I mean by a "growth spurt" - maximizing and living

up to the tremendous gift your subjects are giving you by letting

you be present.

TID:

Do you have advice for photographers looking to gain this level

of intimacy with their subjects?

LOGAN:

Communication with subjects (family or not) is so important,

and finding the right subject is paramount. Everyone has different

boundaries; you probably won't find them all out in one conversation.

You probably can't jump right in with a subject and in the first

conversation ask if it is ok to photograph them naked. But you take

steps - ask to visit their home, and once you are in their home, you

can ask to see inside their bedroom, for example.

Trust is something that is built. You and the folks you are

photographing are constantly building it by exploring private places

and intimate experiences. This growth, this relationship, can happen

many ways and over different periods of time. Sometimes through

jokes and chatting, other times just being around in heavy situations.

Conversations can run in that vein too, where you ask questions

and clarify expectations little by little. It can be very frustrating

when you think you've spelled out needs and have access, then

find yourself shut down in a key moment.

With some folks, I like to ask hypothetical situations in a calm

time, before something emotional happens: "If something

hectic were to happen at your home, how would you feel with

me photographing it?‚” "What would be the best way for me to

photograph __fill in the blank__?"

I try to avoid yes or no questions, like "Can I photograph this?" -

it is too easy for people not to think about it and just say "No."

If it is a long-term project, you are going to be with this/these

subjects for a while and you're going to be having conversations

with them at some points; I just try to find appropriate times to

set expectations.

Logistically, keeping up with subjects is important. Don't assume

anything. Ask them what they are planning on doing later that day,

that week, that month. Reassure them that, yes, even though some

action or activity may seem mundane or commonplace to them,

we as photographers would like to be present and witness it - we

have to be there when things happen.

Be true to yourself, and be real with the people you are

photographing. People can feel when outsiders are being

fake or holding back. I think you really have to be almost

as vulnerable as the people who are letting you into their lives.

There is a process where everyone involved lets down barriers

and goes with the situation. That's when viewers can FEEL

what is happening in the images.

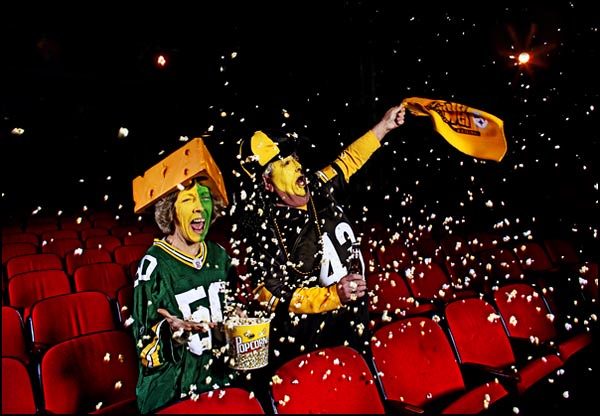

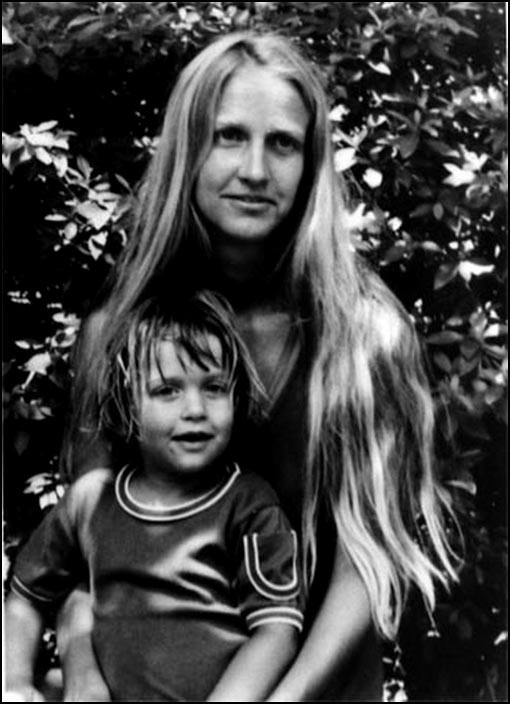

Please show this old B&W photo of me and mom. I really don't

want people just to think of her as "somebody who died" or

another "Subject in a Cancer Story."

She is my Mom, and I miss her very much. I'd love it if THIS

is how people could remember her.

Thanks so much Logan.

+++++

Logan has photographed in over a dozen countries for a wide variety of

editorial and advertising clients. His images have been published in books,

magazines and newspapers all over the world, including: TIME, Newsweek,

National Geographic Adventure, WORLD Magazine, People Magazine, USA

Today, Los Angles Times, The Guardian (London), as well as on the front

page of the New York Times, Chicago Tribune, Washington Post and the

International Herald Tribune.

He's been recognized with several national and international honors and

grants, including awards in Pictures of the Year International, NPPA's Best

Of Photojournalism, the Alexia Foundation for World Peace, National Hearst

Competition, the Public’s Best Picture of the Year Award on MSNBC, and

North Carolina Press Photographers Association.

You can view his work at:

www.loganmb.com

+++++

Next week on TID, we'll take a look at this image:

As always, if you have a suggestion of someone, or an image you

want to know more about, contact Ross Taylor at: ross_taylor@hotmail.com.

For FAQ about the blog see here:

http://imagedeconstructedfaq.blogspot.com/