TID:

Melissa, great to feature your work with TID.

We appreciate you being willing to share your insight.

MELISSA:

I'm really excited by the idea behind this blog, so thank

you so much for asking me to take part in this.

TID:

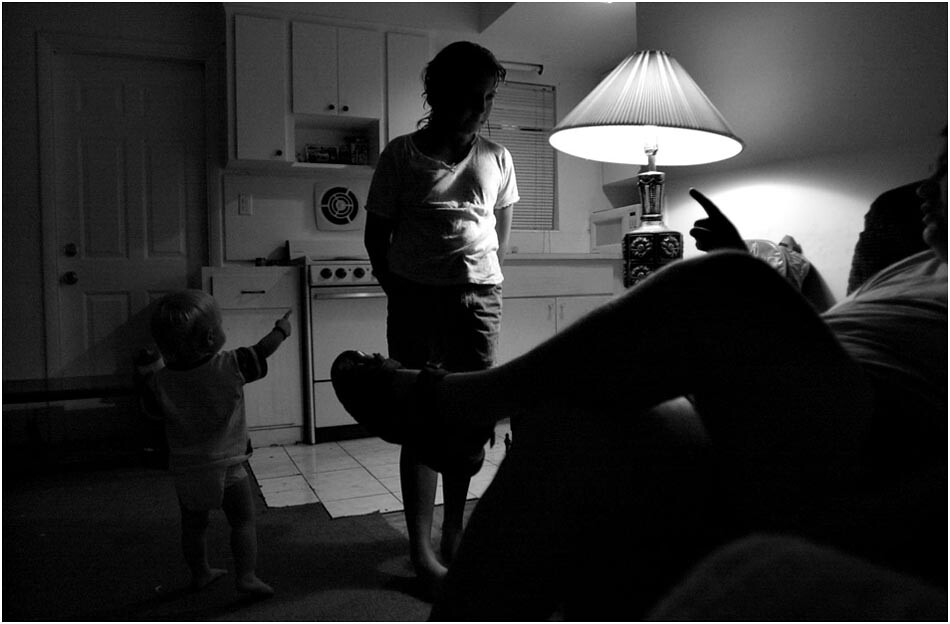

You have a number of strong, intimate pictures (it was hard

to pick one), but we'd like to feature this picture from the

Kids in Chaos story.

Your access to the family was moving.

If you recall, I emailed you after it was published and asked

you how you gained such intimacy. You didn't know me

back then, but were kind enough to respond.

And now years later, we're back and retracing it, but this

time sharing some of your insight with a larger audience

than one.

Lets now talk about the backstory of the image.

Tell us how you first met this family, and how you began

the story.

(TID NOTE: The pictures in this post were the images taken

moments before and after the featured image)

MELISSA:

I was assigned to photograph a daily story about how

people, especially families, were given weekly vouchers

to stay in nearby motels since many shelters were full.

The initial assignment just said to meet this family at

the motel. I had no idea what I was getting into. From

the moment I walked in, the family accepted me.

They were incredibly open and unguarded in their moments.

I had kids hanging off of me by the time I was leaving,

calling me Aunt Melissa. The story was running the next

day, and for the paper's purpose their story was over, but I

had promised the kids that I'd come back the following

afternoon so they could show me how they'd learned to do front

flips in the motel's swimming pool.

I made some time in between assignments the following day to return.

When I pulled into the parking lot, I saw a few of the kids

outside, and as I was getting my camera out of the back of

my car, one of them said "Aunt Melissa, Aunt Melissa -

we're moving, we're moving."

I ran up stairs to find Mark and Dempsey (the parents).

Evidently, the motel management had beef with them

over how clean their room was, and kicked them out.

So the shelter that had initially placed them, sent a van

over to move them into transitional housing.

I called the paper and told my assignment editor that this

was a bigger story than we had thought, and asked if there

was anyway I could get out of my next assignment. I

wanted to ride with them to transitional housing to see

where they were being moved and more importantly to

figure out why.

I had only been at the paper for about a year at that point,

and had never really worked on a big story before. I sensed

that there was something more there, but wasn't sure what

yet, all I knew was my gut was telling me to follow them.

(Note: I was deeply moved by a story Daniel Anderson at

the Orange County Register had just done the year before

on Motel Children. I had a friend working at that paper and

he sent me a copy of it when it published. It went onto win

the Community Awareness Award in POY, and was a Pulitzer finalist.)

TID:

Access is built over time, and it's clear to me that you spent

a lot of time developing trust with the family. Can you let us

know how long you think you spent in total on the project

(and with this, can you talk about your time management)?

MELISSA:

According to the digital files, the first day was with them was

May 17, 2001. I worked on it through the end of the year,

because just after Thanksgiving, the Stones moved up to

Baltimore with family to get back on their feet. I made one

trip to Maryland to finish the interviews, because at this point

I was writing the story, too.

So I worked on it for about 6-7 months.

I spent a lot of time with them, just hanging out, camera

down, talking. The Stones lived in 5 or 6 different places

while I was working on their story, and there was no real

way to get ahold of them - part of the reason I'd drop by

so much was so I didn't lose them.

They were good about calling me when stuff was happening,

but it was always from a nearby pay phone, and there was no

way to call them back. I knew it was important that I was

there as much as possible, but I also knew I needed to dig

deeper and find what pictures I needed to make.

It was important for me to have an honest conversation

with when I needed to be there for in order to tell their

story fairly. Early on, that's what a lot of my visits were.

Conversations.

TID:

Now that we have a good idea of the time and origins

of the story, lets move to the picture. Can you tell us

where this picture fits in with the story, and about the

time leading up to the image.

MELISSA:

I'd try to schedule my time so I could put myself in

the right situations to witness those bigger moments,

but I'd also make it a habit of dropping by their house

after I got off work, to shoot the moments in between.

That's when this picture was made - after work one night.

The time stamps show I was there for 90 minutes, from 7:30

until 9 p.m. I shot 134 frames that night - most of them

horrible, A lot of them blurry and out of focus.

I was just responding to the moments of the chaos, and trying

to push the heck out of a Nikon D1 in really low light situations.

TID:

Given this, can you talk about the moment of the image,

and please include how you were feeling at the time.

MELISSA:

The caption on the photo read: After using a cuss word in

front of not only her parents, but also her younger brothers

and sisters, Meghan, 10,gets a lecture from dad and a less

harsh, but similar gesture from her youngest brother Matthew, 1.

It happened so quickly, and it was over before I knew it.

I literally shot two frames of this scene.

I was in the other room photographing Dempsey changing Piglet's

diaper, so I don't even remember Piglet being up and in this frame.

He was at that stage though where he was mimicking a lot of

words and gestures that the others did, so it was a really pleasant

surprise to see him there in the bottom corner of the frame,

mimicking his dad pointing at Meghan. She had a lot of

pressure on her being the oldest, and the funny thing is,

I think she was just mimicking words she'd heard adults

say when she let a cuss word out.

I remember being struck by Meghan's body language,

defeated, hands behind her back and she took her

punishment, but I don't really think I even knew what

I had until I got back and looked at it on the computer later.

TID:

At any point was there any conflict with the family

or anyone else – meaning, did anyone ever object

to your presence or ask you not to photograph?

If so, how did you handle this?

MELISSA:

No, the family never objected. In fact I think

I was kind of a nice distraction from reality sometimes.

The hardest obstacle was getting a hold of them.

I think at one point I hadn't been out to visit them

in a week or so, and I dropped by to say hi and they

were gone.

Luckily, I was able to track them down again through

a church group that they'd been working with. That

was the nature of their lives, though, at the time,

constantly in transition and in chaos.

I knew when things were going astray and they were

being moved from one transitional housing center to

the next, picking up the phone to call a photographer

wasn't always a top priority (nor should it have been).

Everything went pretty smoothly, the only really

bureaucracy I faced was when I had to explain to

the school officials why I was interested in photographing

one of the kids in class.

They finally agreed, because they had a lot of kids

in similar situation, and they let me in.

TID:

This was relatively early in your career, can you talk

about how this project impacted you as you started working on it?

MELISSA:

It was a year into my first staff job, and it was the biggest

story I had worked on. I think I made a lot of mistakes,

I learned and grew a lot from them, and it impacted me

greatly, by solidifying that this was what I really wanted to

do with my career. For me, the real power I gained came

from going beyond the daily assignment, in recognizing

the potential that something bigger was there beyond just

the tip of the iceberg that I was initially told to photograph.

It taught me to question things more, to follow my curiosities

and to trust my instincts.

Most importantly, it taught the importance of being a

photojournalist, not just a photographer.

TID:

In closing, what advice would you give to photographers

who want to dig deeper and build better access with

the people they are photographing?

MELISSA:

I'd say the most important thing is to approach stories

and your subjects with an open mind and not let

stereotypes or your own insecurities shape the story you're telling.

I can't stress enough the value of having an honest

conversation with people about why you're there, what

you want to be there for, and asking them what's important

for you to photograph in order to tell their story fairly and honestly.

I've found that the best told stories are ones when there's

somewhat of a partnership between you and your subjects.

What this story taught me, and what I've carried with me

into every other story I've done since, is that ultimately it's

not your story - it's their story.

You have to respect that and let your subjects guide you through it.

Melissa Lyttle is a staff photographer at The St. Petersburg Times,

and founder of:

www.aphotoaday.org

You can view her intimate, award-winning work at:

www.melissalyttle.com

+++++++++

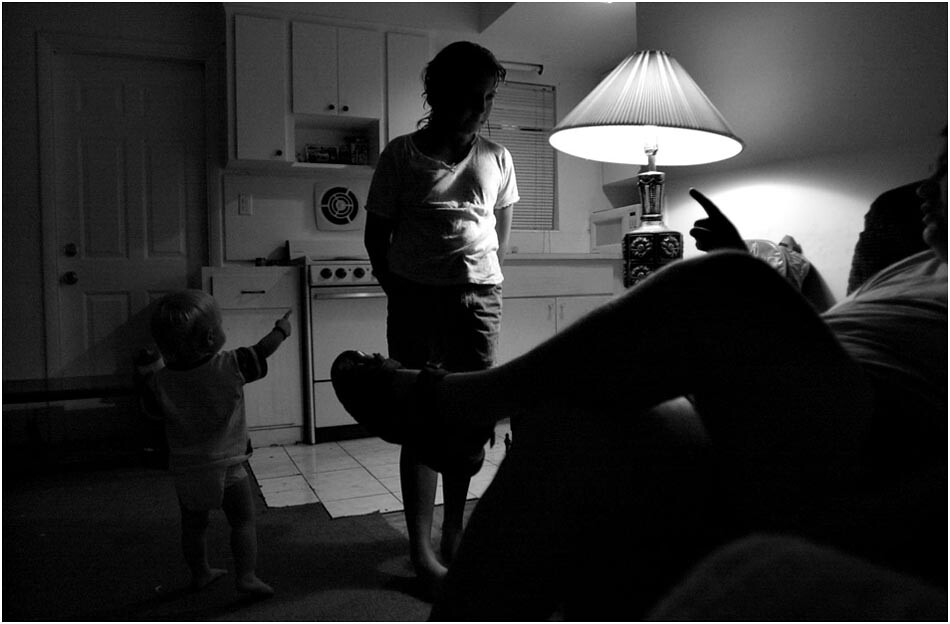

Next week on TID, we'll spotlight this image:

And, as always, if you have a suggestion of someone, or an image you

want to know more about, contact Ross Taylor at: ross_taylor@hotmail.com.

For FAQ about the blog see here:

http://imagedeconstructedfaq.blogspot.com/

No comments:

Post a Comment