Your exponential growth over the years has been

impressive, and it's great you're willing to lend insight

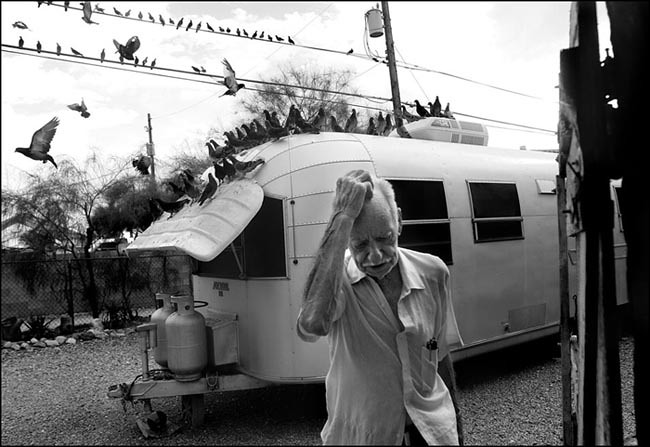

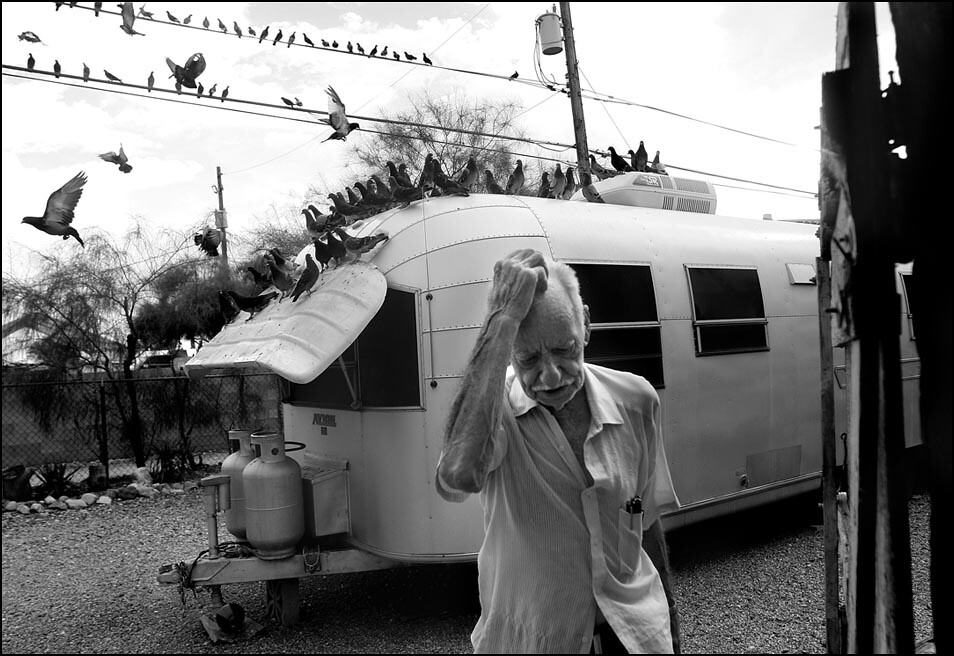

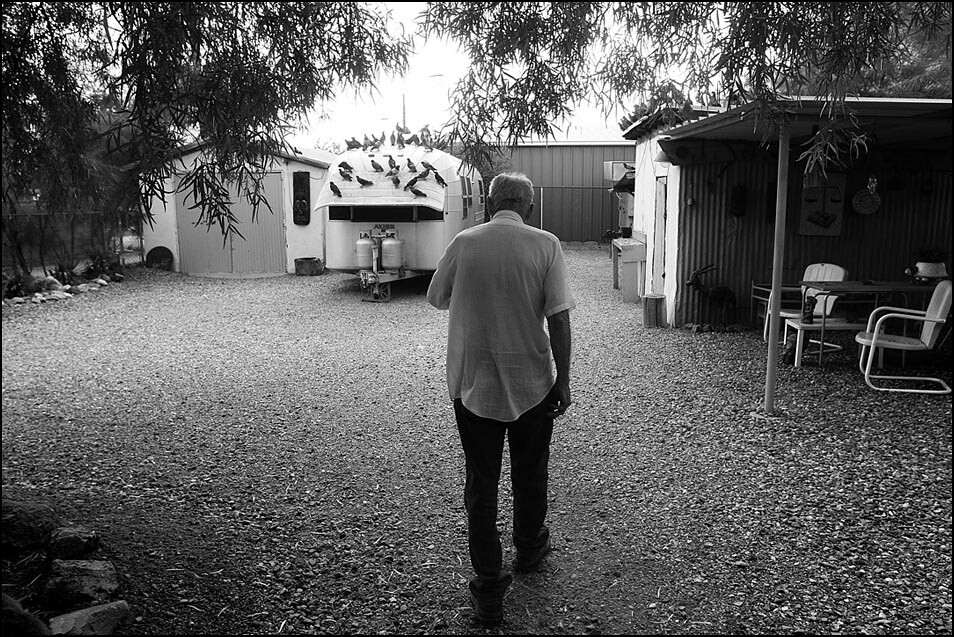

into your thinking. One of the pictures that stood out

was this image:

JAMES:

Thanks so much for the opportunity to share here. The

thought behind the work is so important, and I know the

advice I receive from people, workshops, or through reading

has impacted how I approach my photography.

TID:

We'll take a break this week from the usual interview style

and just have you recount the story behind the image, which is

interesting in it's organic development.

JAMES:

I was fighting a "tunnel-vision" mentality a the time – the mentality

that's easy to get into when working for a newspaper. It's easy to get

into - you go to your assignment, you shoot what is expected,

then you go home. Day after day it can be a grind. It can make your

senses and your pictures dull. I was working on ways to challenge myself

when I made this image, on a day when I had no assignments.

For me, most of the work that I've done comes from enterprise,

looking for images that inspire me in some way aesthetically,

or pulling on a thread of interest that I find when I meet people

that grab my attention. Sometimes that can come from assignments,

but more often than not, I find them on my own.

I was driving back to the office after lunch when I saw a man painting

a day care building. I had an impulse to stop but I kept driving,

thinking "Nah, I should just go, there will be another time."

I thought about the danger of “tunnel-vision” and went back.

I attempted shooting him for about 15 minutes but it just wasn't

working.

That's when I spotted Ken (the man in the photo) trimming the

hedges of his yard. I also saw what looked like hundreds of

pigeons on telephone wires near his back yard. I thought it

was more interesting than the original reason for stopping.

I walked to him and asked him why there were so many

pigeons. He responded, "They're waiting for me to feed them.

It's almost time" he said. I thought to myself, “Jackpot.”

I talked to him for awhile, and I told him I thought the scene was

interesting and I asked if I could hang out with him for a bit and

make some pictures. In this case, it helped Ken understand what I

wanted to do, so that when he went to to feed them, he would just

do his thing, naturally, instead of worrying about what I was doing.

Then I started to think about what kind of image I wanted to

make. I loved the old Airstream, the birds, the sky, and of course,

Ken. I wanted to make an image that incorporated all in one.

There wasn't much color, but the textures and contrasts were

great, so I knew it would stronger as a black and white imahe.

That's important because it affects how I approached shooting

the scene.

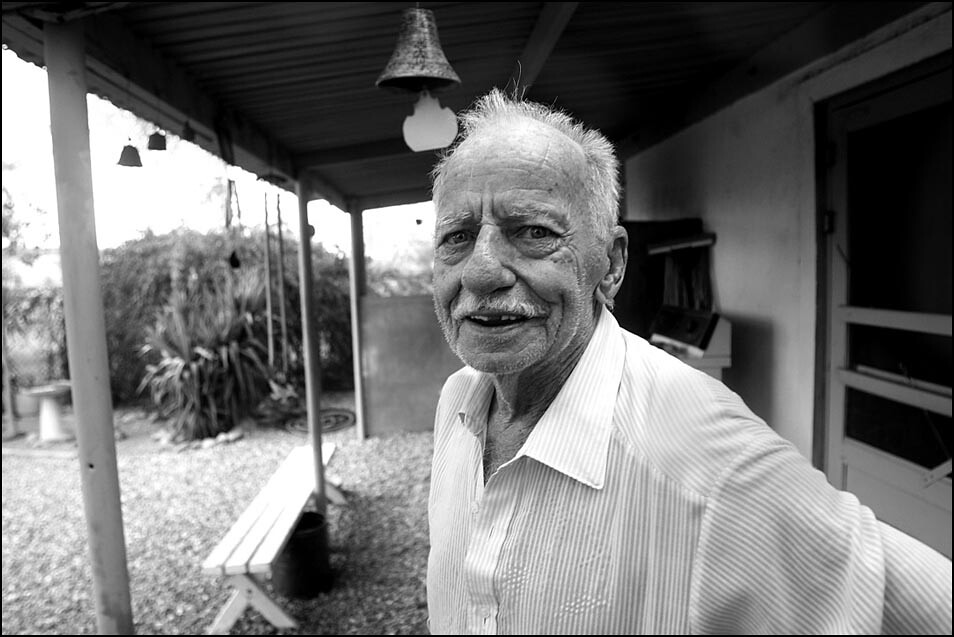

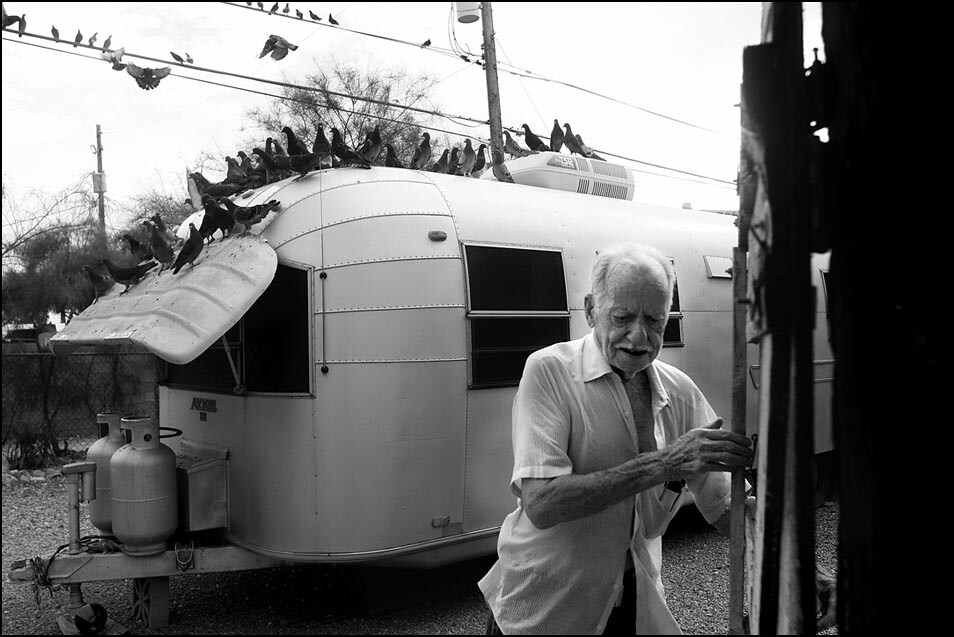

He was pretty talkative and not used to having a camera

around, so I made a few pictures of him as we talked. The first

couple are awkward, but I do this a lot with people who are

shy because it kind of breaks the ice. I'll never use that picture,

but it's really helpful because it helps me get to the good ones where

people are relaxed.

I also make a couple that help me feel how the light is working around

the scene I'm interested in, and it also helps me anticipate the best

position to be in.

I thought I had the right position in the following images. They had

everything I wanted: the airstream, the old shed, sky, gravel,

Ken. I was excited because I thought, this is it, I'm in the right spot.

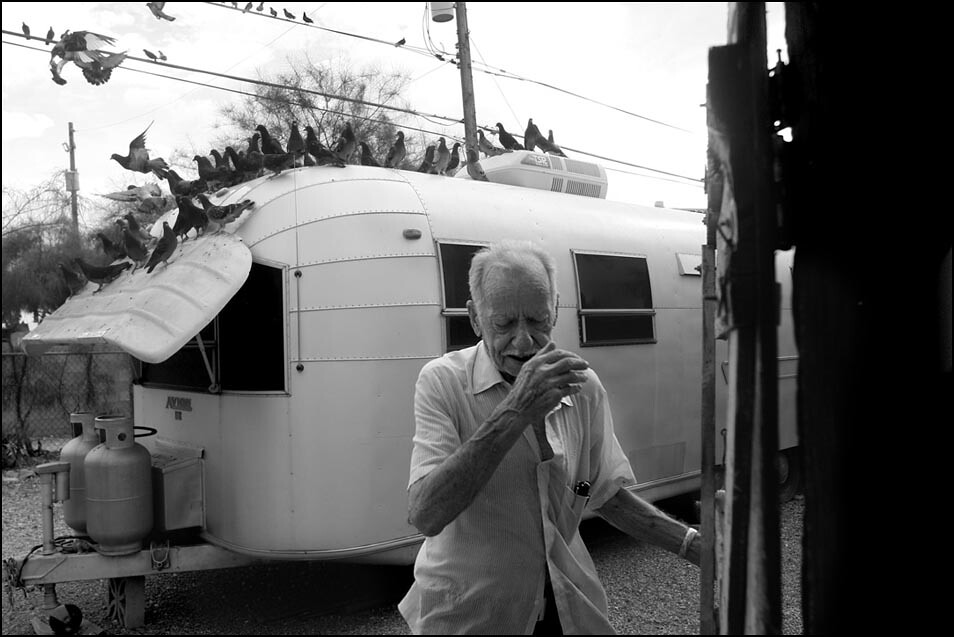

Even when I've put myself in the best, well-thoughtout spot, I find

there is always at least one thing that is totally out of my control,

and that's the moment. The more complicated the attempt, the

more moments are out of my control and the less chance that they

will come together at the right time.

At the beginning when he was spreading seed it was working, but

it's missing a moment, like the birds in the air. He said the birds

were afraid of me because they didn't know me. Luckily, that wasn't

the only scoop of seed Ken was spreading, so I would have other

chances.

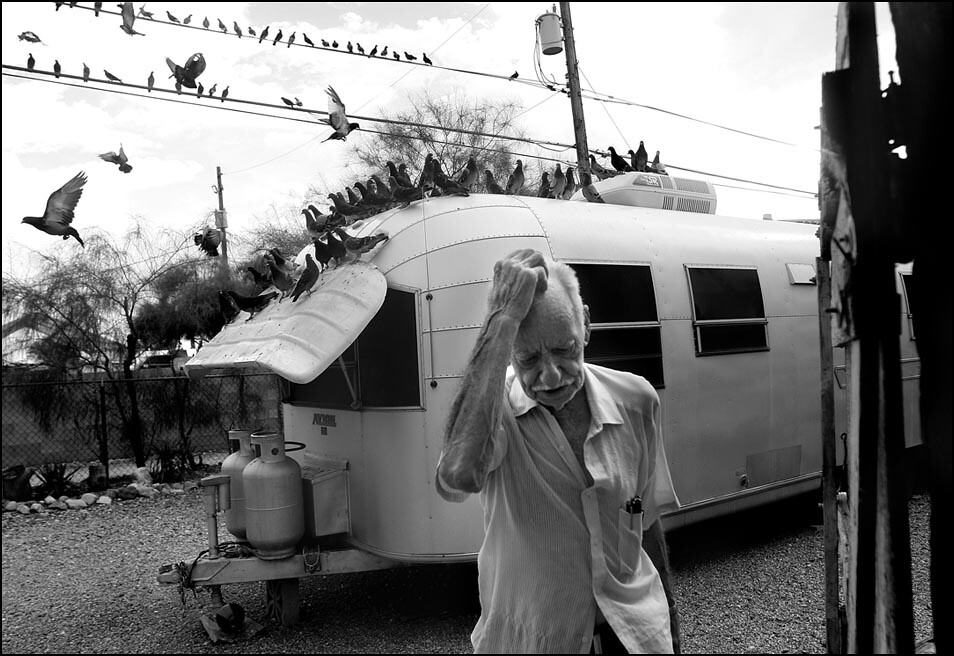

I ducked inside of the shed in the hope the birds would be more calm

and fly down to him on his next trip. He started chatting a lot again,

and then I check the way the light was hitting him in the doorway.

The whole time I'm thinking about how that Airstream and the birds

are looking in the background.

When I saw how the door opened I chose my position and

hoped for the moment, just like before. This time, it worked a lot

better I think. Part building the elements together as I learn about

my subject and the environment, and more than a little luck.

TID:

Thanks James, in conclusion, what advice do you have for

photographers to get into these type of situations, situations

that are not part of the daily assignment?

JAMES:

My advice would be to listen to that little voice or impulse when

you're driving down the road or going about your day in "tunnel

vision". Be open to exploring situations and never, ever, settle for

going day-to-day, grinding out assignments without looking

for ways to stretch yourself. You will find interesting people, great

experiences, and more interesting pictures. It's not easy, but when

it pays off, it will feed the soul for a long time and inspire you to

reach out again.

++++++

James Gregg was named 2009 Photojournalist of the Year, Smaller

Markets, by the National Press Photographer's Association's Best of

Photojournalism. He was named First Runner-Up for the honor in 2008.

The Arizona Press Club named him Photographer of the Year in 2009 for

the second consecutive year. He has received two regional Emmy awards

for his work in multimedia.

James recently joined the staff of the San Diego Union-Tribune as a

photographer/videographer. You can view his work at:

www.jamesgreggphoto.com

++++

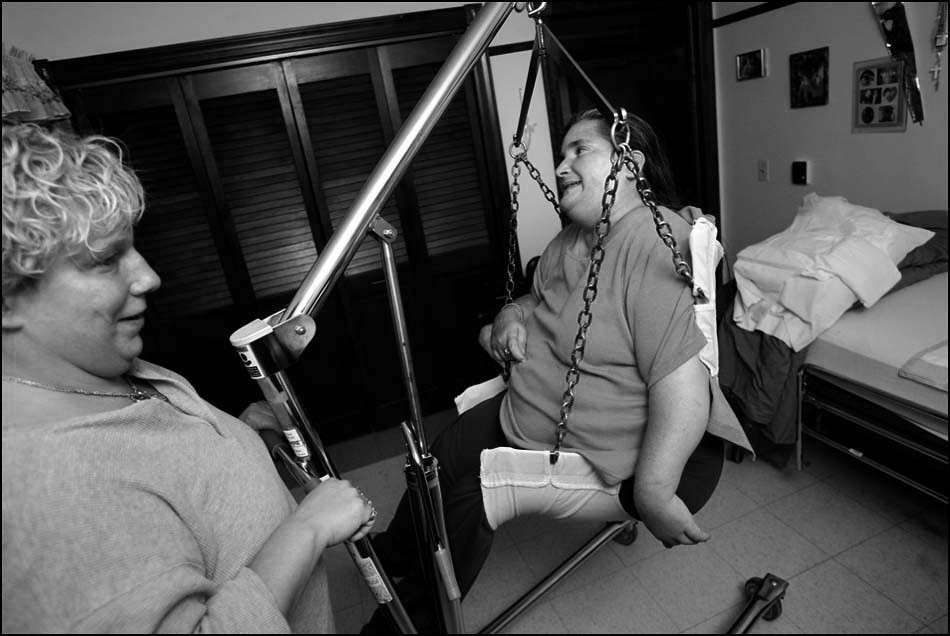

Next week on TID, we'll take a look at this image by Rachel Mummey,

this year's College Photographer of The Year:

As always, if you have a suggestion of someone, or an image you

want to know more about, contact Ross Taylor at: ross_taylor@hotmail.com.

For FAQ about the blog see here:

http://imagedeconstructedfaq.blogspot.com/