TID:

Scott, thanks so much for being open to this. I have to

start by saying thank you for allowing us to talk about such a striking,

powerful image.

What is the background behind this picture?

SCOTT:

Thanks Ross! I am honored to be included here. I have been

following TID religiously and I enjoy it immensely.

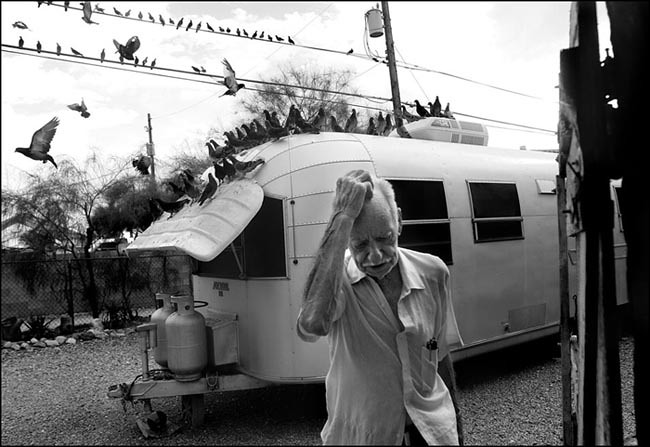

This image, taken on July 2, 2002, was the culmination of my

documentation of Harlow and Jean Cagwin’s family farm in

Lockport, Illinois, 35 miles southwest of downtown Chicago.

The story started as a daily newspaper assignment on various

people who raised animals in Homer Township.

After the story was published, I continued to follow the Cagwins

as a personal project. I didn’t really have any concrete idea of what

I wanted to do with the images, but I did know that I enjoyed being

on the farm and felt the need to make photographs there.

As time went on, certain themes started to present themselves and

I just went with the flow.

The project began as a series of “a day in the life” photos of two

senior citizen cattle farmers. The Cagwins led a very redundant life

so I would shoot their daily chores over and over again. This approach

allowed me to perfect images and try out different angles and lens

choices. Basically, the farm was a self-taught story-telling workshop.

As time went on Harlow’s body began to break down and the focus

of my story began to turn towards Harlow’s health issues. Shortly after

that, I started hearing conversations about the family farm being sold

to a subdivision developer.

Once that scenario started to present itself, I knew that suburban sprawl

was what the story would eventually be known for.

TID:

How long had you worked on this story before you made the

image?

SCOTT:

I first met the Cagwins in 1994.

After the initial meeting, I intermittently visited the Cagwins over

the next 5 years. I didn’t accomplish much photographically but I

did establish access and a comfort level with the Cagwins that would

be crucial in later years. In 1999, I started making a point of getting

out to the farm on a weekly basis and it stayed that way until July 2, 2002.

TID:

Now, on to the image. How were you able to arrange to be there

during this moment?

SCOTT:

Once, I began hearing rumblings of the sale of the Cagwin farm in

late 2000, I started to think about the final day. I had endless conversations

with Harlow and Jean about how everything would play out, about their

future plans and about their feelings as the end of life on the farm neared.

Construction of the subdivision started almost a year before the Cagwins

moved and as each day passed, the Cagwin farmland got smaller and smaller.

There never was any doubt that I would be there on their last day. It was a given.

TID:

What was going through your mind at the beginning of

your time with them?

SCOTT:

The final day was intense.

First off, I never once imagined that the day would unfold like it did. The

Cagwins were supposed to be out of their farmhouse in June, but the process

of leaving the house, that Harlow had lived in for 74 years and Jean for 35

years, took much longer than they had imagined. The subdivision developer

kept giving the Cagwins more time to move out but he eventually couldn’t

wait any longer. On July 2, 2002, as the Cagwins gathered the last remnants

of their life on the farm, the demolition crew waited anxiously outside. Less

than a minute after the Cagwins walked out their door, the demolition commenced.

TID:

What was their reaction to you documenting this situation?

SCOTT:

It was a very emotional day for everyone.

Harlow was incredibly cranky. Jean was sad. Harlow’s sister Sandy, visibly

shaken, cried as she visited her childhood bedroom for the final time. A

stream of neighbors stopped by to pay their respects. Except for the occasional

scolding by Harlow, no one seemed to notice that I was there but by that time,

I was a fixture on the farm and people would have noticed more if I wasn’t

there than if I was.

TID:

I can imagine this being a very difficult moment to photograph.

Was there any point during this that you became emotional? If

so, how did you handle it?

SCOTT:

The final moments inside the house were heavy. Harlow and Jean were

bickering and just seconds before they walked outside, Jean’s oldest cat,

spooked by the demolition crews, ran upstairs and hid amongst a roomful of

junk. As Jean headed up to get her, Harlow told her that there was no time

and she would have to leave her pet behind. As Jean left the house, she seemed

to be in shock and Harlow yelled that the demolition could begin. I had always

pre-visualized that I would photograph Harlow and Jean standing together

outside their home as it was torn down but as they left they went separate directions.

I chose to stay with Harlow. I photographed him as he paced around the yard,

stopping to sit, getting up again, only to sit down somewhere else seconds later.

I was trying desperately to get his face and the house demolition visible in one

frame but most of my images ended up being shot from behind.

Jean pulled out a disposable camera and started photographing the scene.

I broke away from Harlow for a minute and photographed Jean.

I then glanced back at Harlow and saw that he had taken up residence on a

felled tree in front of the farmhouse. I framed the scene from behind and

finally Harlow, unable to watch any longer, looked to the ground.

Snap! The moment I had anticipated for almost two years came together perfectly.

Harlow got up, told Jean that he had seen enough and they drove off.

TID:

Since this part of the goal of this blog is to uncover some of the

psychological approach behind the images, can you speak about

your mental approach to these situations?

SCOTT:

My approach is to become part of the family I am documenting.

I share my life. I listen. I socialize. I hang out. I try to get my photo

subjects so comfortable with me that when I show them photos later

they comment that they don’t even remember that I was there when

that particular moment happened.

TID:

What advice do you have for photographers to gain access to these

type of situations?

SCOTT:

Put in the time. Respect your subjects. Share your life. Ask specific

questions about future activities. Visit often but for short periods of time.

Listen, listen and then listen some more. Be respectful but be bold. Don’t

be afraid to photograph uncomfortable situations. You can always not use

an image that your photo subject hates but you can’t go back and shoot

something that you were uncomfortable shooting but unbeknownst to you,

your subject didn’t have a problem with.

TID:

Thanks so much Scott, it's really wonderful seeing this series

of images. They stick out in my mind and have a lingering

sadness and power to them.

SCOTT:

Thanks Ross! I will most likely never do any work that is as profound or

important as this story. For that, I owe a huge debt of gratitude to Harlow

and Jean.

TID:

Any last thoughts before we close the interview?

SCOTT:

I think it is vital that photographers have a lifelong project to fall back

on when they need a photographic escape. The hardest part is starting.

One has to realize that you don’t have to have a fully thought out thesis

to begin working on a long term project. Once you begin shooting, go

with the flow, be open to changing direction but mostly just shoot.

My documentation of the Cagwins began simply and then as it evolved,

it became something different and then when I started photographing

at the subdivision that was built on the Cagwin land, it became something

different again.

It is cliché but the first step is the hardest.

Scott Strazzante, 47, was born and raised in the shadows of the steel mills on the far southeast corner of Chicago. The son of a tire dealer, Strazzante first became interested in photography when he started taking his dad’s Canon AE-1 to Chicago White Sox games. After college, Strazzante began what has now been a 25-year career at Chicago-area newspapers, including The Daily Calumet, The Daily Southtown, and the Joliet Herald-News. In 2000, Strazzante was named National Newspaper Photographer of the Year by the National Press Photographers Association and the Missouri School of Journalism.

In 2001, Strazzante, an 8-time Illinois Photographer of the Year, started work at the Chicago Tribune where he spends his time as a general assignment photographer.

You can see some of his work here:

Shooting from the Hip blog:

www.newsblogs.chicagotribune.com/shooting-from-the-hip/

Common Ground @ MediaStorm:

http://www.mediastorm.com/publication/common-ground/

Common Ground- The Blog:

http://commongroundtheblog.wordpress.com/

+++++

Next week on TID, we'll take a look at this image by James Gregg:

As always, if you have a suggestion of someone, or an image you

want to know more about, contact Ross Taylor at: ross_taylor@hotmail.com.

For FAQ about the blog see here:

http://imagedeconstructedfaq.blogspot.com/

Such a powerful moment... It is been eight years, I wonder if they are still hurting?

ReplyDeleteNot only such a powerful moment, it is timeless. It's really special when you look at these pictures, you cannot tell if these are 8 years old, or where taken yesterday.

ReplyDeleteAnd with people losing their homes today, I felt these images symbolized what's going on now.