In this week's installment we take a look at this

image by Rich-Joseph Facun:

What a lovely image Rich. It's both subtle and complex

at the same time. I understand this image is part of a larger

project. Before we get to the image, can you let us know

about the story on which you're working?

RICH:

First and foremost, thank you for inviting me to take part in

The Image, Deconstructed. I appreciate your interest in my

work and taking the time to lend an ear. I’ve been following

the blog and it’s been insightful.

Essentially, the image is a single component from a larger

project I’ve been working on in India entitled Darshana Ganga.

Darshan(a), is a Sanskrit term meaning "sight", vision, apparition,

or glimpse. Ganga refers to the Ganges River that runs 1,560

miles from where it rises in the western Himalayas to where it

rests at the Bay of Bengal. For centuries it has been considered

the holiest of all rivers by Hindus and worshipped as the goddess

Ganga.

I initially started working along the banks of the Ganga while on

holiday in Varanasi. After returning from India I was consumed

with anything and everything Ganga related. I read literature, bought

several photo books that featured India, drove around listening to

classical tabla Indian music, and spent endless hours online

researching the river.

I decided to return to the Ganga and begin a series that conveyed

the spiritual, ritual, and daily significance of the river to Hindus and

Indians in general.

Having self-funded the project, I’ve only been out to India three

times for a total of about three weeks. There is a certain liberty

in answering only to yourself. In doing so, I feel a sense of freedom

and independence. I can shoot what I respond to emotionally, simply

because I want to, as opposed to looking for an image to illustrate

an issue or story that may or may not be an actuality.

TID:

I used to have the idea that making powerful images while out of the

country was easy, just because things seemed so, well, foreign to us.

I was foolish enough to think there was some sort of “red carpet” for

photographers while out of country. That, of course, was ridiculous,

and it showed how inexperience and uneducated I was.

In fact, it's quite hard working in different cultures. Can you talk about

your experience working in India and specifically along the Ganges river?

RICH:

There is definitely a misconception that shooting in a foreign land

lends itself to making great pictures easier. Quite often it’s the

opposite, at least for me. Prior to moving to the United Arab Emirates

I too discredited the value of work shot abroad by photojournalists.

However, being dispatched to multiple countries and continents in

this region I’ve found how naive my previous perception was regarding

foreign work.

At best, when working abroad, your greatest challenge will only be

logistics. Unlike the States, getting to where you need to be

geographically isn’t as simple as hopping in your car and following

a map or your GPS.

For example, the destination where I shot the photo above

required multiple forms of transits. It started on a metro and

continued with a bus ride full of pilgrims, a quick hand rickshaw,

then switched to an auto rickshaw. From here I caught a ferry

where I crossed the Ganga Delta. Next, I hiked through barren

farmland and then hired a taxi that took me to Gangasagar Island.

In rural areas along the Ganga, to some extent, the language

barrier became an issue. Knowing how to say “thank you” in the

subject’s language wedded with an honest smile goes a long way.

You can’t lean on opening up to a subject by sharing personal

stories, however, so trust has to be gained by other means. You

learn to maximize your personal resources. You’re forced to grow

your nonverbal communication skills. It can be a challenge.

Picture yourself as the only Westerner hanging out with almost

half a million pilgrims on a remote island in the Bay of Bengal.

A few people spoke broken English but only enough to ask my

name, where I was from, if I had a wife, and if I had any babies.

I was as much an anomaly to them as they were to me.

In Varanasi, the community was vibrant and fairly open to being

photographed. However, one immediate challenge was catching

people in candid moments that conveyed sincere emotion and

color. People in India love to stare A LOT! It’s a cultural thing

and it’s not meant to be disrespectful but feels more like a

childlike curiosity.

Because of this obstacle, I often found myself shooting an

excessively gross amount of useless frames just to render one

decent image. Sometimes it worked and a lot of times it didn’t.

On the other hand, I also hung out in areas where I felt a picture

might happen, just waiting for things to unfold.

TID:

We'd like you to explain what lead up to the moment.

RICH:

Once I arrived at Gangasagar Island, I immediately headed to where

the Ganga met the Bay of Bengal. I wanted to have a chance to scan

the area and get a feeling for what the atmosphere, light, and overall

vibe was on the beach. I arrived during the start of the Gangasagar

Mela where an estimated 300,000 to 500,000 Hindu pilgrims traveled

to dip in the waters where the Ganga ends and meets the Bay of Bengal.

I shot a few frames to measure the light and define how the camera

rendered the scene. Looking out into the bay I immediately knew I

needed to make some type of image that perhaps was a visual epitome

of the river’s spiritual, cultural and daily significance. I wasn’t sure this

was something I could do or accomplish but that was what I felt I needed

to consider attempting.

The frame from that first evening looks out into the bay and catches

a few people lingering about. Its essentially an early sketch of the next

day’s image. Making sketches before actually arriving at the final image

is something I do often. Sometimes the sketch is not at all related to

the final image I end up making but gives me an idea I can apply to

other situations.

In this case, I was able to see how the light looked during that time

of the day, I could see the cold blue being rendered in the frame as

the sun was soon to set. It was almost 8:00 pm. From this, I decided

that it wasn’t exactly the light I was hoping for nor did I think it would

render the story I wanted to emulate in one frame. But it was a rough

start. Additionally, I was able to estimate where the sun would be the

following day and prepare accordingly. It’s pretty basic photo 101

logic but it works, right?

The next day I started at sunrise but didn’t head off to the beach right

away. I roamed around the pilgrims’ campsites and the rest of the

grounds. I still wanted to get a better feeling for the people, place

and overall energy.

When I made it down to the water I shot the sky, the earth, the wind,

a naked man, a holy cow, everything, ya know? Eventually I started

playing around with getting something ethereal and esoteric. Looking

back at the shoot, I found that I started working this idea around

11:30AM for a few minutes and then a little over an hour later came

back for another attempt. I still came up short.

With almost half a million people on the beachfront one main challenge

was to find the order amid the chaos. I wasn’t too concerned in

finding something that showed the overall magnitude of the festival.

That was not my priority so I kept looking and shooting.

Much of the time I had to keep encouraging myself to push on. (I

often had a one man conversation going on in my head while shooting.

I’d elaborate but it’s probably not suitable for print). I was especially

anxious since I felt like after traveling all that way I still had not made

anything worth keeping. I know, patience is a virtue but it wasn’t my

greatest strength. Not that day.

At this point I decided to give it a rest and just play a little more. I

stopped worrying so much and just diverted to doing a bit of a street

photography.

Almost two hours later I made a frame that started to really excite me.

The layers were starting to come together, the lighting and choice

of exposure lent themselves to a particular mood I felt but had not

been able to translate into an image in previous frames. Moreover,

the colors popped, adding another dimension to the composition.

Things were looking up! I kept working it for a few more minutes

but to no avail. I moved on but was feeling optimistic.

As I roamed the area looking for other images that would provide

visual punctuations in my project it dawned on me that maybe I was

forcing the picture and trying way too hard. So I backed off,

figuratively and literally. I ended up shooting a couple wide frames.

In the second of these two frames some of the elements that are

present in the final image clearly started coming together.

As I continued working the situation I saw a man off in the distance

walking back to shore. His body language immediately attracted me.

The pronounced arc in his appearance, his delicate walk awash in

a sea of color were captivating. I anxiously waited for him to

approach the shore hoping he would ignore me and my camera.

Thankfully he did.

At this point I had something, however, it was loose and could use

a crop. Not too mention I knew it still wasn’t quite there yet. I paused

again, pulled back, and shot off another frame.

I knew I was getting somewhere, that something was finally happening.

In the following minutes, as I’m sure many photographers have

experienced, magic happened. I found a rhythm. Here, in this place,

everything lined up. Externally, elements such as the light, subtle

body language and textures presented themselves. Internally, I

stopped thinking, I stopped trying, I stopped shifting, I stopped and

an effortless clarity took over.

In this moment the family walked into the right side of my frame...

TID:

Lets get to the image. What was going through your mind the moment

the main image was made?

RICH:

To be honest, I wasn’t really thinking at that point in the process.

It doesn’t happen that often but every now and then everything just

goes into some zen-like mode where there is some synchronicity

happening both internally and externally and the next thing I know,

I’m walking away with an engaging image that I have never made

before. I think this probably happens to a lot of people. Not just in

regards to photography, but everything from sports to plumbing. I

remember having the same feeling when I was dishwasher.

Seriously, I kid you not. One moment there were a pile of pots,

pans, salad bowls, plates, and in the next few moments they were

gone. I just get into a zone and from the moment it begins until it

ends I’m pretty much in auto-pilot. You just flow.

TID:

Was there any point of conflict, or a moment people didn't want you

to take their picture? If so, how did you handle it?

RICH:

I can’t recall any specific time when anyone protested having

their photo taken. As in the States or anywhere else I’m working

I just read my surroundings, the environment, the people, the

situation and then go from there.

There were a few times when certain people didn’t want to be

photographed and I respected that. In those instances I just smiled,

thanked them, apologized for the disturbance and moved on, no

big deal.

That said, I was specifically turned away once when I was trying to

gain access to photograph Manikarnika, the main burning ghat in

Varanasi. Manikarnika is a holy site where hundreds of cremations

take place daily along the banks of the Ganga.

After haggling with the “untouchable” who manned the ghat, he

said I could shoot anything I wanted for eight hours if only I were

willing to give a “donation.” As much as I wanted to work here the

idea of paying it didn’t sit right with me so I opted out.

TID:

What advice do you have for photographers who want to work

on projects out of the country?

RICH:

Let me back up a bit. Before I earned my living as a photographer

I always wanted to travel. I wanted to experience the road and the

world. I had a couple opportunities to travel abroad from my time as

a sponsored skateboarder but I never went. My whole trip was that

I needed to know my own country before I went galavanting into

someone else’s. It just didn’t feel right. So I traveled the States, lived

out of my truck and saw as much as I could. Eventually I made it

abroad but I guess I needed to do it my way. Now, I’m out here.

Personally, I never understood why people would want to leave their

own country and pursue projects elsewhere. My advice is: don’t. Stay

home and advocate stories that address the issues that are happening

in your neighborhood, your community, your home.

This probably sounds hypocritical since I now live in the Middle East.

But I moved here to live long-term which I think is a little different than

parachute journalism.

Not to be a obtuse, but I just think people should look at the States

and think about all of the untold stories. There are so many issues

out there that are rarely addressed. Generally speaking, domestic-

based journalists and documentarians need to dig deeper and

challenge themselves and challenge their audiences, myself included.

You don’t need to travel half way around the world to show me that

kids are dying due to inadequate healthcare. This is happening in

the States! You don’t have to travel to Afghanistan or Libya to show

me there is conflict. America is facing more conflict now then it has

seen in a long time. The wars in America are just fought with

different weapons. What’s wrong with fixing the good ol’ USA?

The point is there are so many issues being ignored or simply lacking

representation in the States. Why not tell the story of the downtrodden

at home before jumping on a plane and parachuting into some region

that you really know nothing about and more than likely won’t have

the resources to do the story properly.

Look at Eugene Richards' “Dorchester Days,” Scott Strazzante’s

“Common Ground,” Barbara Davidson’s “Frozen Land, Forgotten

People" or “Stray Bullets,” or Matt Eich’s “Carry Me Ohio.” I think

these are stellar examples of what can be done in your own

backyard. All four of these photographers have utilized the

resources of their immediate community.

Personally, I don’t think I’m the best person to talk to about doing

work on projects out of the country. I’ve always considered myself

a community journalist, and I still do. Besides, there are so many

other people, young ambitious people, who are in the early stages

of their careers, that could give much better advice based upon

their recent experiences. People like Carolyn Drake, Krisanne

Johnson, Sarah Elliott, Dominic Nahr, Justin Mott, Kevin German,

and the boys over at www.dvafoto.com. Ask one of them - they’re

smarter and more knowledgable than me when it comes to working

abroad.

However, if you still want to jump ship and try your hand at shooting

a project in a foreign country here a few things that might help:

Bring your own toilet paper.

Baby wipes are a life saver.

Less is more - pack light.

Don’t drink faucet water.

Only eat in busy cafes frequented by locals (good sign you won’t

get food poisoning)

Bring a great pair of comfortable walking shoes (I have one pair

that have been to eight or nine countries)

Make sure you pick up some voltage convertors

Rent the cheapest hotel - you’re there to shoot, not lounge poolside

Simple precautions go a long way. Use your noggin.

Leave your ego at the door. Respect the local culture.

All that said, this is a rough generalization about working on projects

out of the country. There are of course people like Jon Lowenstein

whose long-term essay “Shadow Lives USA,” eventually extended

some of his coverage into Mexico. I can get onboard with that.

And of course, sometimes people are just curious or have a passion

for something outside of their homeland and must saturate that

yearning by going abroad. It is what is. In the end, do what is right

for you but like I said, bring your own toilet paper.

+++++

Rich-Joseph Facun was born in Florida to an Otomi Indian mother, and a Filipino father. His photography specializes in documentary projects that investigate history through fringe cultures and trends in societal norms. It is in these topics that he explores the phenomena of personal independence, the pursuit of dreams, and the discovery of self-identity. Facun has been a working photojournalist for over a decade. In that time he has covered news, feature stories and photographed high-end commercial campaigns spanning a dozen countries.

Currently, he is working as a staff photographer at The National in Abu Dhabi, and is a contributing photographer with arabianEye and Getty Images’ Global Assignment division.

Facun’s work has earned multiple accolades in Pictures of the Year International, the National Press Photographer Association’s Best of Photojournalism, The Atlanta Photojournalism Seminar, and the William Randolph Hearst Foundation, amid others. Additionally, while working at The Virginian-Pilot he was awarded the first and second place Portfolio of the Year by the Virginia News Photographer Association for two consecutive years.

You can view his work at:

http://www.facun.com/

++++++

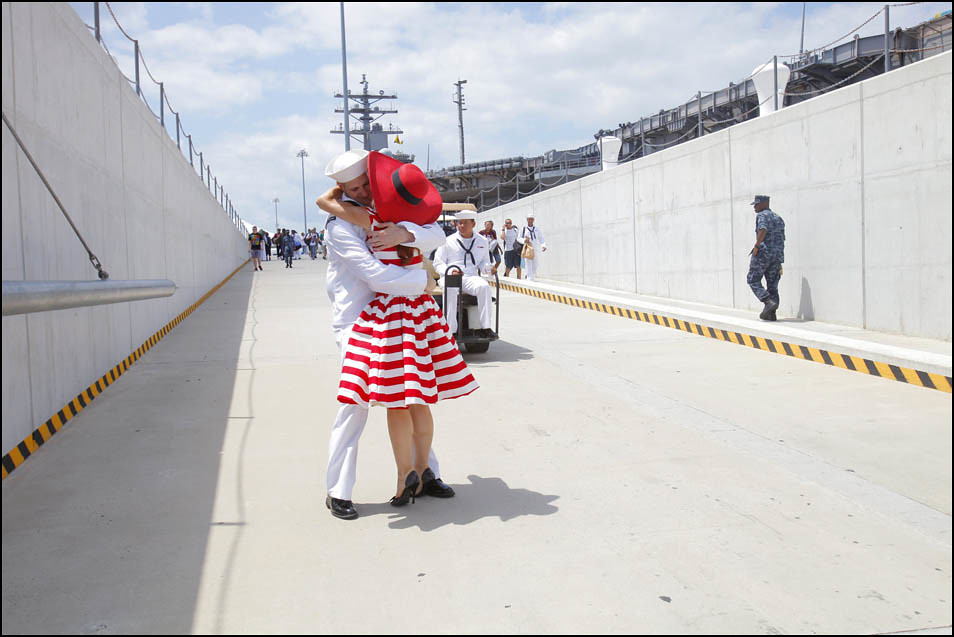

Next week on TID, we'll take a look at this unique image by Scott Lewis:

As always, if you have a suggestion of someone, or an image you

want to know more about, contact Ross Taylor at: ross_taylor@hotmail.com.

For FAQ about the blog see here:

http://imagedeconstructedfaq.blogspot.com/