image by Amanda Lucier:

TID:

Can you tell us how you got the idea for

the photo series, “While You Were Gone”?

AMANDA:

Every few months at the Virginian-Pilot, a different

photographer takes over the photo column “Common

Ground,” and works on a thematically-linked series of

images and text. I was lucky to get a chance to work on

the column during my first year here, and I wanted to find

a part of the community that was underrepresented

in our coverage. I had interned for thirteen months in

Indiana at a very small paper, and I missed the sense of

intimacy and connectivity I had with the community;

I guess I was looking to recreate that experience here, in a

bigger place, at a bigger paper.

The military was a natural community to explore and we

didn't cover military families as much as I thought we should.

So I brainstormed with a friend about how to tell the stories

of military families and the title “While You Were Gone,” just

hit me. I asked myself, “What would it be like to be away from

someone you love for so long?” That seems like a particularly

poignant kind of sacrifice-- not a dramatic, frantic situation,

but a quiet, deep kind of experience, which is what I tend to

look for when I make images.

TID:

How do you generate ideas for the series, and how much

time per week would you estimate is dedicated to the series.

AMANDA:

I didn’t really generate specific ideas for images I wanted

to make, I just focused on meeting as many different people

whose loved ones were deployed and let stories find me in

way. It was a lot of work. I must have hounded every public

affairs officer (PAO) within a 100-mile radius for the three months

before I began shooting, figuring out who would be deployed

and just getting permission to talk with Family Readiness

Groups.

Note: A PAO is a military personnel assigned to mediating

interactions with journalist.

Once I got permission, though, the stories flooded in.

I would go to events for families, parties, cookouts, even

deployments themselves, just to talk with people and get to

know them. People were overwhelmingly interested in sharing

their lives, showing what life looks like without someone at

home. But I can’t overstate how leg work at the beginning was

crucial in developing contacts and finding stories. I worked

those phones and my email every single day, sometimes going

up the chain of military command if I wasn’t getting a response.

I’m not a super-aggressive reporter, so it was a good experience

to fight for access.

TID:

It takes a lot of time working on this series, so how do you

balance the series with your daily work?

AMANDA:

Honestly, I did a lot of shooting on my days off because family

events and milestones seemed to fall on those days and I never

had to reschedule with a family if I wasn’t on the schedule at

the paper. Additionally, one day a week of my regular schedule

was taken up with writing, researching or shooting. I was given

a lot of freedom by our assignments editor, Bill Kelley, to have

at least one day a week to devote to the column, but I think I

probably worked on it every single day in one way or another.

It’s funny, now that I’ve had two months of only daily assignments,

I’m feeling the void of not having a long-term project and I’m

working to start up some new stories. A project reminds you what

it’s all for when you’re elbows-deep in business portraits and

restaurant reviews.

TID:

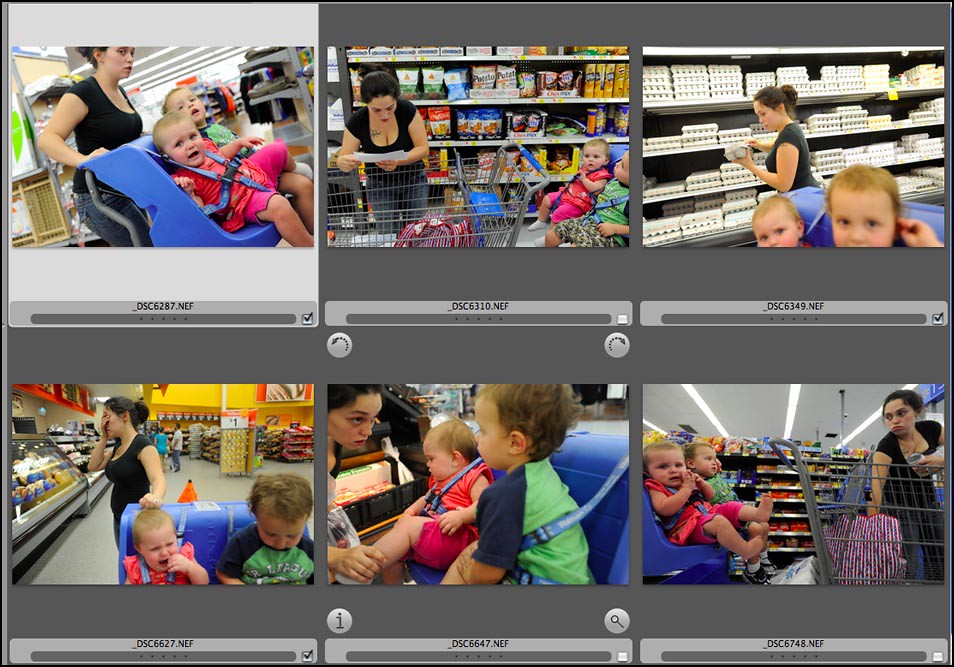

Now, to the image. Can you tell us how you met this

woman and what her story is?

AMANDA:

Mary Brazie called me after I got her name from her Family

Readiness Group leader. We must have talked for an hour and a

half, about her relationship, how she met Tyler, how deeply she

loves him, and how she was faring without him. She told me

that cooking and shopping was the hardest thing without him,

and invited me on a trip to Walmart. I loved the idea of

photographing her in such as prosaic setting; there’s nothing

inherently visual about Walmart, but my intent with the series

was to show daily life, no matter how unromantic, and it seemed

to be the perfect place.

TID:

It'll be helpful to know how you went from this information to

generating this image. Tell us the context of the image, how

you constructed the parameters for achieving it, and the moments

leading up to it.

AMANDA:

I don’t have much profound to say except that I followed this

woman around Walmart with her two kids who fought and

cried constantly, and I photographed them. My heart went out

to her-- two kids, all alone, missing her husband and struggling

with everyday chores like going to the grocery store. I could

hear people around her tsk-tsking that she left a crying baby in

the cart, instead of picking her up, and I wanted so much for

people to be compassionate instead of judgmental; I’m sure they

would have been kinder if they had known her story. She was

doing the best she possibly could with a cranky kid and WIC

coupons on some random weekday morning at a Walmart in

a new town. I just focused entirely on her and her experience,

on how frustrating it was for her, and I made that picture.

I decided beforehand to just shoot her, without getting permission

from Walmart. That can be such a hassle, and either you are

denied or someone follows you around for the whole time and

that changes the dynamic. I figured that if someone approached

us I would just explain the project and we would be fine.

TID:

What was going on in your mind as you made the image?

AMANDA:

I was thinking about trying to show her frustration but also giving

context as to WHY she was frustrated. I was thinking about

framing so you could tell it was a grocery store, but also so it

included the kids. When they started to fight like that, I felt like

it was all coming together, and I kept shooting, kept moving,

until I got it.

TID:

Was there any point of conflict or any objection to you

making this image? If so, how did you handle it.

AMANDA:

It was actually the opposite; Mary completely understood my

project, why I was there and what I needed to photograph.

She acted as if I wasn’t there until we got out to the parking

lot. She wanted her husband to see what she was going through.

TID:

Do you have advice for photographers who want to work

on an ongoing photo series like this?

AMANDA:

Find a friend who is also working on a project. I’m lucky because

of the staff at the Pilot, and also because of my neighbor Matt Eich

who pushed me to think about less obvious ways to tell the story of

deployments. Anticipate a ton of work. Photographers need to be

reporters, and the better the research and preparation, the better

the picture making opportunities. We need to stop thinking that

editors and writers will do that part of the job for us. It makes the job

more demanding, but also more focused. Putting effort into research

and conceptualizing stories before we even begin shooting is a best

practice if we consider ourselves to be journalists as well as photographers.

The only limit to what you can do at a newspaper like the Pilot (and,

actually, all the papers I’ve worked for) is what you expect of yourself.

It’s not fun to work hard at a desk and on the phone, but it paves

the way for successful storytelling. I had to be an advocate for the

presentation of the series online as well, and as uncomfortable as it

can be haggling about fonts and JavaScript, no one else will fight as

hard for your stories as you. I learned that from Preston Gannaway.

Amanda Lucier is a staff photographer with The Virginian-Pilot.

She was recently named Virginia Photographer of the Year.

You can view her work at:

http://www.amandalucierphoto.com/

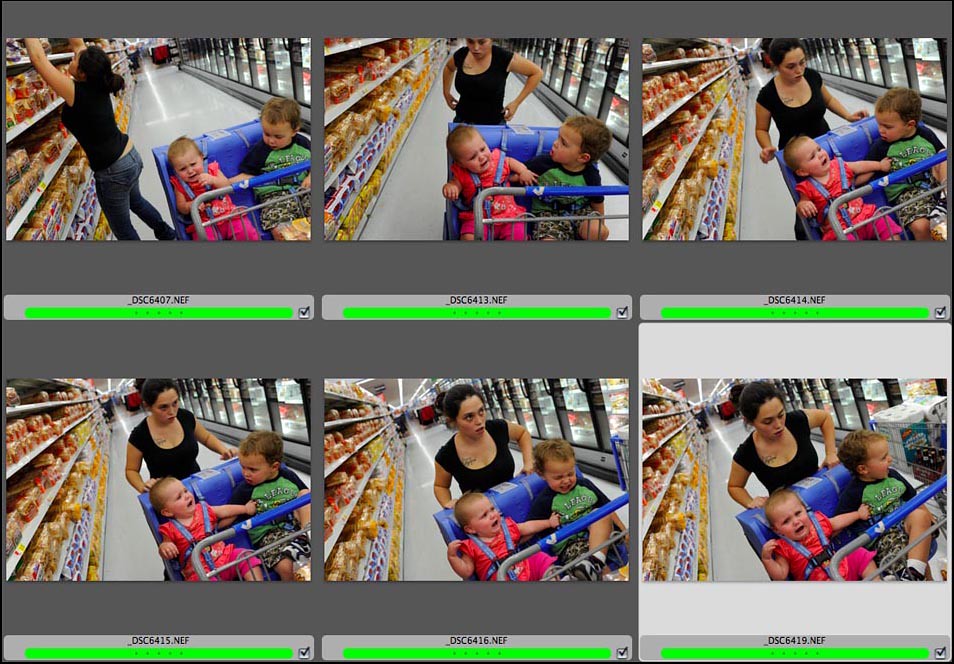

++++

Next week on The Image, Deconstructed, we'll take a look at this image

by David Holloway:

As always, if you have a suggestion of someone, or an image you

want to know more about, contact Ross Taylor at: ross_taylor@hotmail.com.

For FAQ about the blog see here:

http://imagedeconstructedfaq.blogspot.com/

No comments:

Post a Comment