Jason, thanks for taking part in TID. Please tell us

about this image:

JASON:

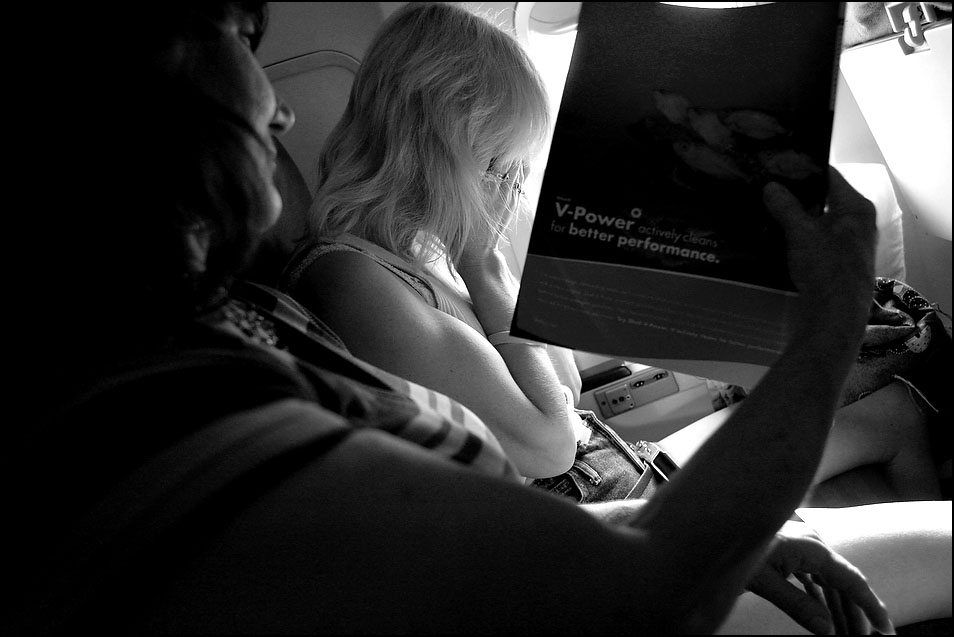

This image is of Rachel Reich, it was included in a story that I

photographed for the Winston-Salem Journal newspaper in 2006.

Her story ran as a daily story for the paper, then a reporter

named Paul Garber and I decided to pursue it as a longer term

project. Rachel was battling cancer in her mouth and contacted the

newspaper because she thought she had a compelling story to share.

She had battled and fought cancer several times before, even as a

young woman, and each time hadn’t taken chemotherapy or radiation.

This time, her doctors said she would have to have a radical surgery

to save her life. The surgery would have put her unborn baby at risk

and would have left her unable to eat or speak for the rest of her life.

These were risks she was not willing to take. She had her baby, but

by then it was too late to do the surgery. She was hoping that bringing

her story to light would open up opportunities for more non-traditional

treatments that would be very expensive.

TID:

How did you get access to this moment?

JASON:

Rachel was an amazing person and a great subject. She allowed

me into her home from the first day I met her, and the access that

she gave us was one of the reasons we wanted to follow her story.

The other reason was because a lot of things were going on in her

life. It was a crucial time in her life and there was so much unfolding

every day. Her house was close to the newspaper where I worked

(15 minutes) and once our initial story ran about Rachel, my photo

editor at the paper was very good about allowing me to spend my

down time between assignments working on this project.

After our first story about Rachel was published, there was an

outpouring of support from people who wanted her to beat this

cancer. Rachel was going to go to Houston, TX to seek an

experimental cancer treatment from a clinic there. She basically

viewed this as her last chance to beat a cancer that doctors said

would take her life before the end of the year.

I told her that Paul and I wanted to go with her on the trip, and

she agreed almost immediately. Her mom, two kids and best friend

were already going on the trip with her so I knew a lot of moments

would be happening and I wanted to be there while they unfolded.

Throughout the story, which I had been working on for a few

months at this point, I had a strong connection with Rachel. In

addition to her cancer, she had a lot of family problems. She was

being pulled in a lot of directions. She was very sick and trying to

take care of a newborn baby, as well as a rebellious teenager who

snuck out of the house all the time. I think that she viewed me as

some kind of therapist. I would spend hours at a time at her house,

watching her take care of the baby or folding clothes, but often

times just listening to her and talking. I think she saw time spent

with me as some kind of escape from the chaos of her life and saw

me as a way to validate some of the very difficult decisions she had

made in the recent months.

TID:

Did the newspaper pay for your travel?

JASON:

Paul and I scheduled a meeting with our editors to pitch the

idea that we should travel with her to Texas to document her

efforts to get treated. At that point, her story had run on the

front page of the newspaper already and we felt our readers

would have an interest in following up. I remember the first

pitch to the editors, and how excited Paul and I were, and how

great of a pitch we made. I also vaguely remember it being well

received and walking away thinking it was a ‘go’ all we needed

was a sign-off from our managing editor.

Well, that sign-off never came.

So I told Rachel the newspaper wasn’t going to pay for me to go,

and she offered to pay for me. Obviously, I wasn’t going to let her

do that, but it definitely made me feel like it was something I

should follow through with. I struggled with the notion of self-

funding the trip. I remember when I found out I could get a

plane ticket for under $200, and could get a seat with Rachel

and her mom I seriously considered it as an option. The final

straw was when I found out my 4 consecutive days off at the

paper (during a schedule change) landed when the trip started.

I bought my ticket that day, and decided I would spend my

days off in Houston with Rachel. From that point on, I always

viewed this is more of a personal project and I would be much

more protective of the images I made from that point out.

TID:

What was going on in your mind in the moments

leading up to the image?

JASON:

I met Rachel at her house as she was preparing for the trip with

her mother. Everything was happening very fast and I remember

it was total chaos. Somewhere amid the chaos she told me she

was afraid of flying, and had actually looked into other options

for getting to Houston. I don’t really remember considering NOT

having my camera with me on the plane but I didn’t really have

a plan for what, if anything, I would shoot from that one vantage

point I would have on the plane ride.

TID:

Now, onto the picture. Tell us what is going on, and what you were

thinking and feeling at the time.

JASON:

I remember being concerned that I didn’t know Rachel’s mom

very well. She would inevitably end up in photos but she wasn’t

as used to me being around. In one image you can actually see

that she’s leaning out of the way of the photo, but I wanted her

in the frame. It was a few seconds early, before she really noticed

I was shooting that I made the frame that ended up being in the

final edit.

It was an intense moment for me, Rachel was flooded with

emotions right before we took off and she wasn’t feeling well

physically either. But unlike some of the other images from the

plane where she looked very ill, I wanted an image to capture

her hope that she could be healed.

TID:

How do you handle your emotions while documenting not only this image,

but the entire story, especially in the more trying moments for her?

JASON:

I tend to connect emotionally with the subject when I’m not

actually shooting, and that helps us both feel comfortable

sharing close physical space. I remember with a lot of the

photos from this story, not really wanting to take the photos,

but feeling like I would because that’s what I was there to

do. I think that’s how I know I’m making a good storytelling

image, when I have to break through some mental block that

says ‘maybe don’t shoot right now’. I just shoot a few frames,

get what I need for the story, and go back to just being

around as fast as possible. I think a good photojournalist has

to come to peace with being uncomfortable sometimes.

TID:

Was there any moments of conflict or reservation during the

making of this image?

JASON:

I remember on one side of me was Rachel’s mom, to my right

were more passengers who had no idea what I was doing, and

walking up and down the aisle are flight attendants that probably

knew nothing about Rachel except that she came in a wheelchair

and looked weak.

There’s a ‘rule’ I learned at my first newspaper internship.

“Shoot first, ask permission later.” Of course it’s not always

the best idea but I think it would have been much more

difficult to get official ‘permission’ to shoot photos on the

plane. Mentally I justified this because technically I was there

on my own dime, with my own camera, so at that moment I

was less of a media representative and more of Rachel’s

personal documentarian. I was very selective about when I took

my camera out and just had one lens with a quieter body (Canon

10D, I think) so that I wouldn’t bring much attention to myself.

I didn’t show any of the other passengers or ever point my

camera anywhere besides Rachel’s direction. I didn't shoot

much at all during the actual flight, but mainly just during the

takeoff and landing and a few frames when she was sleeping

on the plane, which was probably unneeded. And once I made

the frame of her with her mom before the takeoff, I was able to

check the back of the camera and see I had a frame that would

work as a good transition to get her to Texas so I didn't feel

like it was worth the risk of disturbing her and possibly the

flight to get more images that would probably land on the

editing room floor.

TID:

What surprised you most while you were with her on the plane?

JASON:

Rachel was a religious person, but I wouldn’t call her devout.

She went to church sometimes, and usually alone. This image

shows her saying a prayer to herself, something I had never

seen her do. Throughout the process of documenting her story

I saw her turn to faith when she felt most alone and most

desperate (I also documented her attending a miracle healing

service after she returned from Texas).

TID:

What lessons did you learn from the making of this image, and

how does it apply to your future work?

JASON:

The main lesson was the importance of documenting transition

in people’s lives. I remember my newspaper editors talking

about sending the reporter and I down for a day or two to check

in on her in Texas because of a scheduling conflict with covering

shifts at work. And I felt like it would be better to be a part of

the trip, and part of the transition to her life there. It’s hard to

explain to ‘non-visual’ people why you have to be there to

capture those moments. The reason is because usually we don’t

actually know what we are going to see. Good photojournalists

will put themselves in the situations where they can expect to

be surprised.

It's very easy to get frustrated in that situation when you don't

see eye-to-eye with the editors. But over the course of time, if

you can repeatedly bring back images that stand out, the editors

will begin to trust your judgment.

TID:

What mental advice would you have for other photographers

who want to work in this type of situation?

JASON:

With Rachel, I knew that this story was also a learning opportunity

for me. I was up front with her about that, that I was learning from

her and learning how to use my camera to tell these complicated

aspects of her life. Since this story, I feel much more equipped to

tell difficult and complicated stories.

As far as advice, I think you should be able to clearly explain to

your subject exactly why you want to shoot a moment before the

moment happens. It makes your intentions clear, makes them less

surprised when you shoot, helps them understand how you are

processing what they do and gives them the chance to explain why

they may be hesitant to allow you into a certain space. It also does

something that I didn’t put much value on until much later in my

career. It lets your subject know what you are thinking and gives

them a chance to correct you. Giving the subject more of a say in

how their story is documented, and giving them a chance to explain

their actions gives them more buy-in to the story and in the end

makes it more truthful and hopefully more compelling.

I don't remember the exact conversation I had with Rachel about

this, but I can imagine how it would go if I were to have it now.

Probably something like this "Rachel, I'm very interested and I

think our readers will be very interested that you are taking this

trip to Texas for treatment. If I were able to travel there with you,

I think I could be able to get a very good sense of the emotions

that you'll be going through on the trip and help show the effort

you are putting in to beat this cancer." Essentially, every ask of

a subject should be followed by an explanation of why.

TID:

In the end, what happened to her, and how did her life

impact you?

JASON:

Rachel lost her battle with cancer a little more than a year after

this image was taken. Her last effort at a cure was chemotherapy,

but it was too little too late. I remember sitting with her and

talking while she was having chemotherapy one day. I couldn’t

shoot in the area they were giving it because there were too

many other patients around. Rachel asked me if I would come

help her set up her video camera to record a message for her

youngest child who probably wouldn’t remember her. I did, and

that was the last time I remember talking with Rachel.

I moved away from Winston-Salem and started a new job. A few

months into my new job, after Rachel passed away, I got a phone

call and “Rachel Cell” came up on my caller ID. I scrambled to

answer it only to hear the voice of her husband on the other

end of the phone.

He was the breadwinner of the family, and not around much.

He didn’t much like my camera, but he liked me. He said he

was going through some of Rachel’s stuff, and found her phone,

and saw my number and just wanted to call and chat. I don’t

remember exactly what he said but I remember his gruff voice

saying something like, “I just wanted you to know, Rachel

always liked having you around and thought of you as a good friend.”

Jason Arthurs is a documentary filmmaker and photographer based in North Carolina. His work has been repeatedly recognized by the National Press Photographers Associated, Pictures of the Year International and he was twice named North Carolina Photographer of the Year. He worked in newspapers for 5 years, and now freelances for editorial publications including the New York Times, Washington Post and TIME magazine. He also produces short documentary films for non-profits, and is currently directing his first feature length documentary film.

You can view more of his work here:

http://www.jasonarthurs.com/

(has Rachel’s story and the accompanying video)

http://www.chasingthemadlion.com/

(a full length documentary)

+++++

Next week, by request, we'll take a look behind this photo illustration.

We'll talk about the beginning concept to it's construction:

As always, if you have a suggestion of someone, or an image you

want to know more about, contact Ross Taylor at: ross_taylor@hotmail.com.

For FAQ about the blog see here:

http://www.imagedeconstructed.com/

No comments:

Post a Comment